"On July 27th, 1863, with a weak lung and bad cough, I left the fogs of San Francisco and went to Sacramento, and stayed long enough to contract a good strong case of chills and fever, which sent me back to my home in San Francisco, where I contracted a bad cold, which, with a chill every other day, and a bad cough every night and morning, soon had me confined to my room and bed most of the time. "My mother realized that I had to get away to some better, dryer climate, so when Dr. John R. Howard, a friend of ours, suggested a trip overland to Mexico, we both, mother and I, concluded that this was the best thing that I could do. I was soon arranged that Dr. Howard and I should go to Los Angeles by stage, there to outfit for the trip to Mexico.

"A prospector named Jack Beauchamp, whom I knew, called on me one day after I had decided to go to Mexico. I told him of my plans and he said he would go with me if it was agreeable. In two days we started by stage, Beauchamp and my mother helping me to get to, and into, the stage. We stayed the first night at San Jose; the next morning we started, and did not stop only to change horses and eat till we got to Los Angeles, five days and nights travel. "I was entirely worn out, but felt better than I did when I left San Francisco. We, the doctor, Jack, as we called Beauchamp, and I, had arranged to buy saddle horses and a pack horse, and go via Yuma and Tucson to Hermosillo, but in Los Angeles we met the news of a big find of placer gold at Rich Hill in Arizona. So, after getting all the information we could, we decided to go via La Paz, rush off to the new gold strike, then on to the Pima Villages, where we would connect with the Tucson and Yuma road. "We soon had our outfit ready and at San Bernardino two more men joined our party, Cal Ayers and Ben Weaver, a half-breed son of Pauline Weaver. We were very glad of the company of these men, as Weaver had been over the road and knew all the water. The second day from San Bernardino we camped at a spring in a cave of the San Jacinto Mountains, called Agua Caliente. There my horse took a run on his rope and broke it, and started back to the settlements. I tried with the doctor's horse to head him off, but could not. There I was on foot and thirty miles out in the desert from Hobbes ranch, the last white man's place in California at that time.

"I offered twenty dollars to any one who would get the horse and return him to me. Weaver undertook the job, and started right back, after instructing us to go ahead next day twenty-eight miles to an Indian ranch called Toros, where there was grass for our stock, there being none at Agua Caliente. I was to wait for Weaver to come up with my horse. I remained at the spring till about nine o'clock next morning, when a party of men rode up from the east, one of whom I recognized as a Dr. Webber whom I had met several years before at Webber Lake in the Sierra Nevada. I made inquiry about the new gold field, and after telling me something about the new country, Dr. Webber walked me off a few steps from his party, and told me that he had on his pack mule, forty thousand dollars in gold, which he had taken out of his claim on Rich Hill since May, he being one of the eight original locators. ''He also told me that he was afraid of his companions, as they were a bad lot, but he intended to get to Dr. Smith's ranch that night, and then to San Bernardino. I guess he was right about his companions, for 'Boss Danewood,' one of them, was hanged in Los Angeles shortly after that by a mob.

"Dr. Webber also told me that there was a water hole at a point of the mountain, which we could plainly see about eight miles from us. After what Webber had told me about the gold and the nearby water, I became uneasy and anxious to get "on, so I filled my gallon canteen with the warm water, hung my saddle, bridle and other equipment in a mesquite tree where Weaver would be sure to see them, and started to make the twenty-eight miles to Toros on foot.

I drank all my water before I got to the point of the mountain that Webber had pointed out to me, and was getting very tired, and what made it worse for me, the soles were beginning to rip from my boots, a pair I had had made in San Francisco, and they were old and thread rotten. The hot sand would work into my boots and scour my feet until I would have to sit down and empty it out. This was drifting sand, such as formed the sand hills that once stood where Market Street, San Francisco, now is. We were greatly surprised by running smack into an Indian cornfield about halfway to the river. The overflows had come early that year, and some Mohave Indians had reoccupied an old ranch that Weaver knew of. We had a feast on watermelons and green corn that night. The next day I had a chill to pay me, the second one since leaving San Francisco. The first one I had the day following my hard tramp from Agua Caliente to Indian Wells. The chills seemed to come every seventh day, or if it missed the seventh, it would be seven or fourteen days before I would have another.

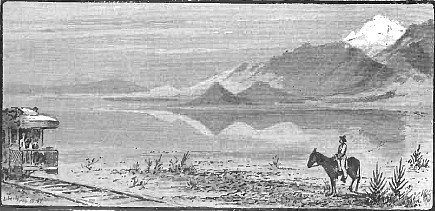

"We reached Bradshaw's Ferry early in the day, but concluded to lay over that day in order to give me a fair chance to shake. We hobbled our horses and turned them loose, as there was good feed along the river. Next morning all the stock but my horse was easily found, Beauchamp, Weaver and Ayers hunting for him till late in the afternoon, when they found him mired in a slough about two miles from the river, with nothing but his head above the mud and water. He was a hard looking horse. We ferried across that evening and landed at Olive City in Arizona. The city consisted of one house about 12x10x10 feet high, covered with brush and sided up with willow poles stuck in the ground, and smaller willow poles nailed on the larger ones without any chinking. However, it was plenty warm enough for the climate. That night we pushed on to La Paz in order to get food for our stock, there being no grass on the Arizona side at that place. At La Paz we bought grass from the Indians, they bringing it from the hills on sticks. The way they manage they take a dry willow pole six or eight feet long, lay down a layer of grass the length of the stick, lay the stick on the grass, then a layer of grass on the stick, and with thongs made of the leaves of a kind of cactus, tie the grass firmly around the stick. In that way they would get fifty or sixty pounds into a bundle, and the squaws would pack it to market on their heads.

"We stayed in La Paz two days, where we found a number of men who had returned from the new diggings at Weaver and Walker. La Paz at that time was a town of several hundred inhabitants with several stores, a bakery and feed corral, but no post office nor mail service. When we left La Paz we followed the Colorado River bottom for thirty or thirty-five miles, where we found quail very plentiful and killed all we wanted to eat. The last night that we camped in the bottom, we stayed at a slough that I learned later the Indians called Supalm. There we met three men coming in from the new mining country. We all camped at the slough and next morning one of the strangers had but one boot, the coyotes having taken one during the night. I still had the old boots with the soles nearly ripped off, and I gave them to the unfortunate one. When we came in sight of Date Creek, we all stopped to feast our eyes on what we all agreed was the most beautiful place we had ever seen. It was a green meadow with grass of different kinds growing all over it, and some of the grass was four feet, or more, in height. There was scattered cottonwood trees and groves covering several acres of the same kind of timber.

Return

to The Arizona Page:

Arizona Gold Rush Mining History