A Historical View, As Written in 1883

The region now embraced within the territory of

Arizona, was first penetrated by Europeans nearly three hundred and fifty years

ago. A quarter of a century before the founding of San Augustine, and long

before Puritan or Cavalier had established themselves at Plymouth Rock or

Jamestown, Spanish adventurers had

explored the wilds of Arizona and New Mexico. Alvar Nunez de

Vaca, one of the followers of Pamphilo de Narveaz, in his disastrous

expedition to the coast of Florida, in 1538, being left by

his commander, with four companions, on the desolate shore, resolved to

penetrate the great unknown, wilderness to the westward and join their

countrymen in Mexico. Without compass or provisions, they struck across the

continent, discovered and crossed the Mississippi two years before De Soto

stood upon its banks and found a burial place beneath its turbid waters.

They traversed the great plains of the West, entered New Mexico, visited the

pueblo towns, passed through the country of the Moquis, and, after many

hardships and privations, joined their countrymen at Culiacan, in Sinaloa.

They gave glowing accounts of the country through which they passed, and their description of the " Seven Cities of Cibola," the Moquis towns, excited the spirit of adventure and cupidity among the Spanish conquerors, and fired the zealous ardor of the missionaries. Padre Marco de Niza, under the patronage of the Viceroy Mendoza, set out from Culiacan in 1539, accompanied by a single companion, in search of the fabulous " Seven Cities." They passed through the Papagueria and the country of the Pimas, by the valley of the Santa Cruz and into the country of the friendly Yavapais, and at last came in sight of the goal of their arduous quest. Father de Niza sent his companion ahead, with some Indians, who had accompanied them from the Gila. The Moquis massacred the whole party. Father de Niza did not enter the city. He set up the cross, named the country the New Kingdom of San Francisco, and returned to Culiacan.

The public mind in New Spain was greatly excited by the news which the good father brought on his return. The thirst for native gold and glory, and the desire to extend the influence of the cross, bore down all opposition. The Viceroy, Mendoza, projected two expeditions to explore the marvelous country to the north; one by land under Yasquez de Coronado, and the other by sea under Fernando Alarcon, In April, 1540, Coronado marched from Culiacan with nearly a thousand men (principally Indians). He visited the ruins of the Casa Grande, on the Gila, and in forty-five days after starting, reached the first of the " Seven Cities." Instead of the rich and populous region which their imagination had pictured, they found a poor and insignificant village. The province was composed of seven Villages, the houses being small and built in terraces, as they are at the present day. The inhabitants were intelligent and industrious. They raised good crops of corn, beans, and pumpkins, dressed in cotton cloth, and were the same in all respects as their descendants, the Moquis and Zunis, are at the present time. Coronado penetrated to the New Mexican pueblos on the Rio Grande, explored the country as far east as the Canadian river, and north to the fortieth degree of latitude. Disappointed in his search for the riches he expected to find, the expedition returned to New Spain in the spring of 1542. The expedition of Alarcon sailed about the same time Coronado marched. The Gulf of California was discovered, and named the Sea of Cortez. The Colorado and the Gila rivers were also discovered. Two boats ascended the former stream to the Grand canyon. For forty years after these expeditions, no further efforts were made to explore the country. In 1582, Antonio de Espejo penetrated the country northward and discovered many popu|ous pueblos in the Rio Grande valley, which are not mentioned by the historian of Coronado's expedition. He visited the Zunis, and passed westward to the Moquis, who met him with presents of corn and mantles of cotton. Forty-five leagues south-westward from the Moquis villages, he discovered rich silver ore in a mountain easily ascended. Numerous Indian pueblos were found in the vicinity of the mines, and two rivers, on which grew wild grapes, walnut trees and flax, were also discovered. Those streams were no doubt the Little Colorado and the Verde.

More than a century elapsed after these explorations before any permanent settlement was made in the territory now known as Arizona. Towards the close of the seventeenth century, the Jesuit Fathers established the missions of Guevavi, Tumacacori, and San Xavier. Missions had been established some time before among the Moquis. In 1720, there were nine missions in a prosperous condition within what is now the territory of Arizona. The fruits of the untiring labors of the zealous fathers were shown in the peaceful and industrious Indian colonies which sprang up around their missions. Despite the expulsion of their founders, the Jesuits, in 17G7, and the constant raids of the savage Apaches, the missions continued to flourish and grow rich, until the revolution for Mexican independence.

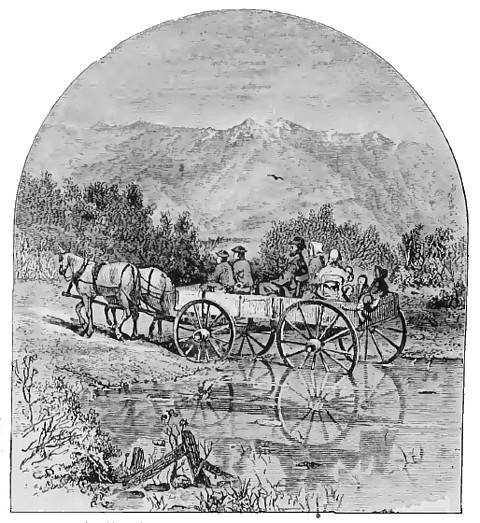

Deprived of the protection of the Spanish government, and constantly harassed by the Apaches, they languished and declined, until they were finally suppressed under a decree of the Mexican government in 1827. By the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in 1846, all that portion of the present Territory of Arizona north of the Gila river was ceded to the United States. At that time the population of the Territory was confined to a few hundred souls within the presidios of Tucson and Tubac. "What is now known as northern and central Arizona did not contain a single white settlement. Outside the Pima and Maricopa villages on the Gila and Rio Salado, and the Moquis towns in the extreme north-east, the savage Apache was lord of mountain, valley, and mesa. In 1854, that portion of the Territory between the Gila river and the line of Sonora was acquired from the Mexican government by purchase. It was long known as the " Gadsden Purchase," the negotiations for its acquisition having been conducted by the Hon. James Gadsden, then minister to Mexico. The price was $10,000,000, and, in the light of its recent developments of marvelous mineral wealth, it can be considered a good bargain. Tubac and Tucson were taken possession of by the United States troops in 1855; the Mexican colors were lowered, the Stars and Stripes hoisted in their stead, and the authority of the United States established where Spaniard and Mexican had held sway for nearly 300 years.

Subsequent to the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the Territory formed a part of New Mexico. A memorial was presented to the Legislature of New Mexico on the first day of December, 1854, for a separate territorial organization. The name first adopted was " Pimieria," but it was afterwards changed to "Arizona." The word Arizona is said to be derived from two Pima words: " Ari," a maiden, and " Zon," a valley, or country. It has reference to the traditional maiden queen who once ruled over all the branches of the Pima race. Before the name was conferred on the whole Territory, it was borne by a mountain adjacent to the celebrated Planchas de Plata mines near the southern liue of the Territory. Arizona remained a portion of New Mexico until the twenty-fourth of February, 1863, when the act was passed organizing it as a separate Territory. The civil officers appointed by the President entered the Territory on the twenty-seventh of December, 1863, and two days later, at Navajo Springs, the national colors were given to the breeze, and the Territorial Government formally inaugurated. The seat of government was established at Fort "Whipple, in Chino valley, on the headwaters of the Verde. It was afterwards removed to Prescott, where it still remains.

The history of Arizona from the establishment of a Territorial organization up to the year 1874 has been a series of fierce and bloody struggles with the savage Apaches, and of slow but steady growth. The intrepidity, daring, and self-sacrifice of the early pioneers, who won this rich domain, foot by foot, from its savage occupants, yet remains to be written, and will be one of the bloodiest pages in the history of our frontier settlements. The hostile tribes were conquered and placed on reservations by General Crook, in 1874, and since that time the Territory has made rapid progress in population, wealth, and general development. With the opening of a transcontinental railroad across the southern portion of the Territory, and the discovery of immense veins of silver ore adjacent thereto, Arizona has attracted the attention of the whole country, and capital and emigration have flowed in upon her at an unexampled rate. One of the first-discovered portions of North America, so long neglected and unknown, is at least beginning to yield up those treasures which for ages have remained hidden in its mountain fastnesses.

Return

to The Arizona Page:

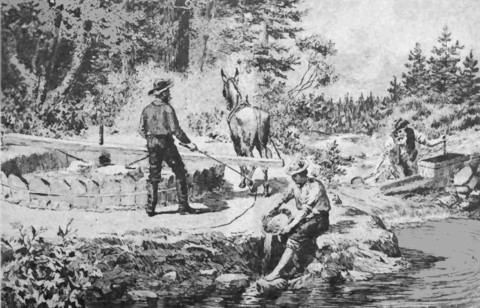

Arizona Gold Rush Mining History