Almost every prospector, whether professional or tenderfoot, had his own pet "lost mine" that he looked for. Hundreds of "lost mine" stories have been localized everywhere over the West. The richest always was somewhere out in the desert, beyond water, or within almost inaccessible mountains, where wild Indians guarded the golden secret handed down to them by their forefathers. Of course, most of these tales were merely inventions or distorted dreams. But the prospector, with only his burro for companionship, was wont to dream strange dreams and, eventually, to transmute them into what he considered reality. On the deserts lie the bones of scores of men who believed these tales and who staked their lives in the search for things which did not exist.

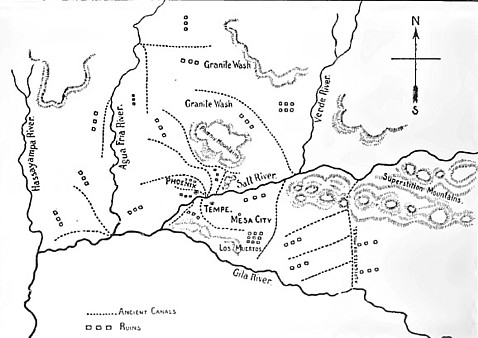

THE LOST SOLDIEROne of the best authenticated of these stories was of the lost ''Soldier" mine. The story has had little embellishment and, in part, may be true. Briefly narrated, it is this: In the summer of 1869 Abner McKeever and family were ambushed by Apaches on a ranch near the Big Bend of the Gila. McKeever "s daughter. Belle, was taken captive. A number of soldiers gave chase. The Apaches separated into several bands, whose trails were followed by small detachments of soldiers, the most westerly by Sergeant Crossthwaite and two privates, Joe Wormley and Eugene Flannigan. Two of their horses dropped of fatigue and thirst and their provisions ran out. Taking some of the horseflesh with them, they struck northerly, seeking water in what is supposed to have been the Granite Wash range of mountains in Northern Yuma County. Water was found just in time to save their lives, for Wormley already had become delirious. In the morning they found the spring fairly paved with gold nuggets. Above it were two quartz veins, one narrow and the other sixteen feet wide. The soldiers dug out coarse native gold by the aid of their knives. About fifty pounds of this golden quartz they loaded on the remaining horse and then set out for the Gila River. Less than a day's journey from the river, the three men separated, after the horse had dropped dead. Wormley reached the river, almost demented from his sufferings and unable to guide a party back into the desert. Men struck out on his trail and soon found Flannigan, who would have lasted only a few hours longer. He was able to tell the story of the gold find, and the rescuing party went farther to find Crossthwaite 's body. In a pocket was a map, very roughly made and probably very inaccurate, on which he had attempted to show the position of the golden spring. Still better evidence was secured a few days later in the discovery of the dead horse, with the gold ore strapped to his back. The ore was all that Flannigan claimed and $1,800 was realized from its sale. Flannigan made several unsuccessful attempts to return to the find, but he dreaded the desert and never went very far from the river. He died in Phoenix in 1880.

The district into which the party penetrated has been thoroughly prospected during the past twenty years and contains many mines of demonstrated richness. It is possible that the mountain was the Harqua Hala. The find might have been the later famous Bonanza, in a western extension of the mountain, from which several millions of dollars in free gold were extracted. Farther west, around Tyson’s Wells, also has been found placer gold, though none of these discoveries seem to exactly fit the special conditions of the Lost Soldier mine. Another lost "Soldier" mine was found by a scouting soldier from old Fort Grant in the hills north of the Gila River, not very far from the mouth of the San Pedro. His discovery was of quartz speckled with free gold. The country about has been thoroughly prospected since that time and mines of importance have been worked in that vicinity, but the nearest approach to the discovery of the old-time bonanza has been in the finding of placer gold in several of the gulches.

Most of the stories of lost mines had to them an Indian annex. Usually the story ran that the Indians would bring in gold and silver ore, but would refuse to tell the secret of their wealth. Ross Browne told in 1863 that at the store of Hooper & Hunter in Arizona City he saw masses of pure gold as large as the palm of the hand, brought in by adventurers who stated that certain Indians had assured them that they knew places in the mountains where the surface of the ground was covered by the same kind of yellow stones. But neither threats nor presents, whiskey, knives, tobacco, blankets, all the Indians craved, could induce the savages to guide the white man to the fabulous regions of wealth. The explanation then was given that the Indians were afraid that the white men would come in such numbers that the Indian preponderance of population would be lost.

THE "NIGGER BEN" DIGGINGS

The most popular of lost mine stories in pioneer days was that of the

"Nigger Ben." A. H. Peeples, one of the original Weaver party, to which Ben

also belonged, in 1891 told the editor what he knew of the legend. Nigger

Ben—and he was a good man though his skin was black—was the only one of us

who dared to prospect around very much alone. The Indians would not harm

him, evidently on account of his color. He struck up a friendship with

several Yavapai chiefs, even when they were the most hostile to the other

miners, and they told him of a place where there was much gold, far more

than on Rich Hill, where we were working. Ben took a nugget from our stock

that was about the size of a man 's thumb and showed it to a chief who was

especially friendly with him. The Indian said he had seen much larger pieces

of the same substance and started off to exhibit the treasure to him. Ben

was taken to some water holes, about sixty-five miles northwest of Antelope,

toward McCracken, in southern Mohave County. When there, however, the

chief would show him no further, seemingly being struck by some religious

compunctions he hadn't thought of before. All he could be induced to do was

to toss his arms and say, “Plenty gold here; go hunt.” Ben did hunt for

years and I outfitted him myself several times and years later he finally

died of thirst on the desert. Numbers of others have tried to find the

Nigger Ben

diggings, but they have not been discovered as yet. Ed Schieffelin,

who discovered the Tombstone mines, wrote me several months ago, asking

about them. I gave him all the information I had on the subject and he is

now out with a large outfit thoroughly prospecting the whole of that region.

I am confident the gold is there.

THE LOST DUTCHMAN

One variety of the "Lost Dutchman" story concerns the operations of a German

who made his headquarters at Wickenburg, in the early seventies. He had a

very irritating habit of disappearing from the camp once in a while, going

by night, and taking with him several burros, whose feet would be so well

wrapped that trailing was impossible. He would return at night, in equally

as mysterious a manner, his burros loaded with

native gold ore of wonderful richness. Efforts at tracking

him failed. The county for miles around was .searched carefully to find the

source of his wealth, which could not have been very far distant. The ore

was not the same as that at Vulture. The location of the mine never became

known to anyone, save its discoverer. He disappeared as usual one night, and

never returned. The assumption that he was murdered by Apaches appears to

have been sustained by a prospector's discovery near Vulture in the summer

of 1895 of the barrel of an old muzzle-loading shotgun, and by it, a

home-made mesquite gun stock. The gun had been there so long that even the

hammer and trigger had rusted away. Near by was a human skeleton, bleached

from long exposure. The next find was some small heaps of very rich

gold quartz

rock, probably where sacks had decayed from around the ore, and then

at a short distance was discovered a shallow prospect hole, sunk on a

gold-bearing ledge. The ore in the heaps was about the same character as

that which had been brought into Wickenburg in the early days by the "Lost

Dutchman“ but it didn't agree at all with the ore in the shallow prospect

hole, which was not considered worthy of further development. In the winter

of '79 some trouble was stirred up among confiding tenderfeet by the

publication of a story in the Phoenix Herald, printed as a fake so plainly

transparent that he who ran might have read. It told of the arrival of a

prospector from the depths of the Superstitions, whence he had been driven

by pigmy Indians, who had swarmed out of the cliff dwellings. His partner

had been killed, and he had escaped only by a miracle. But the couple had

discovered some wonderful gold

diggings, from which an almost impossible quantity of dust had been

accumulated by a couple of days work. The story was widely copied, and from

eastern points so many inquiries came that the Herald editor had to have a

little slip printed to be sent back in reply. On the slip was the word

"lake." The editor feared to even remain silent, for most of the letters

told of the organization in eastern villages of parties of heavily-armed men

to get the gold dust or die in the attempt, and there might have been dire

consequences on the head of the imaginative journalist had

Phoenix been reached by even one

of the desperate rural eastern expeditions.

MINER

The largest exploring and prospecting expedition Arizona ever has known

since the days of Coronado, originated on the tale of a prospector named

Miner. He claimed that he was the only survivor of a party that had found

wonderful placer diggings somewhere near a hat-shaped hill over beyond the

Tonto Basin. From a single shovelful

of earth had been panned seventeen ounces of gold. In May, 1871, he was in

Prescott, coming with several companions from Nevada, and in that month

reached Phoenix from the North with about thirty men. The point of

rendezvous was near old Fort Grant, where were collected 267

men, divided into five companies. At the head of the Prescott party was Ed.

Peck, discoverer of the famous Peck mine at Alexandria. Other members were,

"Bob" Groom, the noted pioneer; Al Sieber, the foremost Indian campaign

scout of the Southwest, Willard Rice and Dan O'Leary. Governor A. P. K;

Safford commanded the recruits from Tucson and was elected commander in

chief of the party at the camp near Grant. From

Tucson and Sonora came two large

companies of Mexicans. From Grant the march was to the Gila, up the San

Carlos and thence to Salt River. There was found the hat-shaped mountain, since known by the name of

Sombrero Butte, and the men prospected widely through the Tonto Creek and

Cherry Creek valleys, and over the Sierra Anchas. Returning down Cherry

Creek, the prospecting was continued up the Pinto Creek and Pinal Creek

valleys. Finally in disgust the different parties separated at Wheatfields

and returned to their homes. Miner, at the time, was thought to have been

mistaken in his bearings, but members of the party later became convinced

that he was merely a liar.

THORNE

Possibly connected with the Miner tale that led Safford and his party very

far afield, was the lost Thorne mine. This story was based on the adventures

of a young surgeon named Thorne, who, having cured the eye troubles of a

couple of Apaches at a post whereat he was stationed, was induced to visit

the Indian village where there was an epidemic of the same disorder. He was

blindfolded, a procedure that usually obtained in stories of this sort, and

eventually reached the village, not knowing its direction. After he had

conquered the epidemic, he was placed upon a horse and taken to a deep

rock-walled canon facing a high ledge of quartz that glittered with flecks

of

native gold. Below, in the sand of the wash, was almost a

pavement of

gold nuggets. Thorne pretended

that the find was of little value, but furtively took all the bearings he

could. In the distance he saw a high mountain, crowned with a peculiar rocky

formation like a gigantic thumb turned backward (a description that might

fit Sombrero Butte) to the eastward of the Cherry Creek Valley. Though the Indians

pressed handfuls of the nuggets upon him, Thorne still persisted in his pose

that the stuff was worthless and refused to take any, convinced that he

could again find the treasure. He led two expeditions into the country, but

found no less than four such formations such as he had marked, and the

bonanza never was discovered, and Thorne afterwards was denounced as an

impostor. It is a fact, however, that the Cibicu Indians of the Cherry Creek Valley knew of the

existence of some rich placer field. On one occasion, Alchisay is known to

have pawned a nugget worth $500 for $10 worth of supplies, and later to have

redeemed the gold, of which he seemed to know the full value.

THE PEG-LEG

In the desert somewhere west of Yuma, many expeditions have searched for the

lost "Peg-Leg" mine, said to have been discovered by a one-legged individual

named Smith, about forty years ago. Some there were who thought the mine in

Arizona, but whatever its location, it has never been found, and may have

been only in the imagination of a rum-soaked prospector.

ADAMS DIGGINGS

Prominent among the "lost mines" stories of Northern Arizona was that of the

"Adams Diggings." Most indefinite are the details, and the various locations

indicated lie anywhere from the Colorado River through to Globe. Adams,

understood to have been a San Bernardino colony Mormon, in 1886 heard from a Mexican a story of a rich

gold deposit, and forming a party of

twenty-two, struck eastward to a point supposed to have been near Fort

Apache, where the "Diggings" were found. The story continues that after

working for a while, eleven of the party started for the Pima villages for

supplies. They failed to return and nine more, driven by impending hunger,

took the same trail, leaving in camp only Adams and two others. The three,

finally driven out by famine, started out and found on their trail, the

bodies of all their comrades, who had been murdered by Apaches. The trio

appear to have succeeded in returning safely to San Bernardino and, in 1875,

to have started, as, members of a party of twelve, to return to the lost

bonanza. Jas. C. Bell, later of Globe, with two companions joined this party

near Prescott and were made members, while four more joined at Fort Verde. The lapse of time had

made Adams very uncertain in his location, but he remembered that it was in

a deep canon running in an easterly direction, at a point where a gold ledge

was sharply defined on the sides of the gulch, and near two black buttes.

Search was made down as far as the Gila, near San Carlos and thence up to

the headwaters of the Gila and back again to Fort Apache, but there was no

success, and still undiscovered are the ashes of an old cabin wherein Adams

told Bell, was buried gold dust worth at least $5,000.

Return

to The Arizona Page:

Arizona Gold Rush Mining History