Cripple Creek is a gold field second to none in the world. Discoveries are made there every day that make poor men rich; but if the visitor expects to see the old miner "bearded like a pard," feasting his eyes on gold nuggets, he will look in vain; and if he expects to see the revolver, the bowie-knife and the Winchester, as furnishings for men, he will be disappointed. The Cripple Creek crowd might have wandered out of Chicago for all its dress and manners tell of it. It is a hustling crowd, and all sorts of old friends are in it. The faces in the hurrying throng are clean and quick, the clothes are well cut and well set. The stage settings are sometimes rude. The seamy side of many a pine structure is visible to the naked eye. But the actors themselves, like the dukes and ladies who stalk across the boards where " Uncle Tom" hobbled the night before, are so well kept that the contrast is distinctly apparent. The town is equipped with water-works, electric lights and sewers. A street-car line has been surveyed, and cottages, with all the comforts that plumbing can bring, are going up every day. The hotels and restaurants spread as tempting tables as those of any place in the Mississippi Valley. Venison, lobsters, pheasants and quail, and fresh mushrooms, strawberries and tomatoes are among the delicacies that lie in the windows of the markets. The old-time "grub" of the mining camp is not heard of in Cripple Creek. The town is up-to-date.

There are two daily papers. A telephone system and the two commercial telegraph companies connect the district with the outer world. Two bookstores sell the latest fantasies in decadent art and literature. The dry goods stores have "linen sales" and "silk sales" every week. The bargain counter greets the economical family man who thought he was fleeing to "solitude in a vast wilderness." The caprices and whims of latter-day civilization are seen at every turn in this new yellow-pine town. The Kansas City Star says:

"The man who comes to Cripple Creek looking for the picturesque, will have to look beneath the surface. The most picturesque sight in Cripple Creek is the sweet thing in corduroys, leather leggings, white hat and hunting jacket, and immaculate linen, stumbling down the street, reading the uncut magazine, and jostling against the crowd." That is the short of it all. There is no frontier. The railway has abolished it. Cripple Creek is as civilized as towns whereon the moss of centuries has gathered. Yet where the town of Cripple Creek now lies crumpled in a pocket of the mountains, a cattle ranch, five years ago, occupied the land. For twenty years the ranch was undisturbed in possession, save when the Mount Pisgah gold rush boom (a salted boom) broke the solitude for two days in 1884. In 1889 an occasional prospector, with pick and drill, strayed into the camp. For years Robert Womack had been digging holes all over the ranch looking for mineral.

But no one paid any

attention to him. As the other prospectors kept coming in so many holes went

down that cattle fell in, and the cattle upon that creek were shipped to

market maimed and crippled. From this circumstance, it is said, the name

"Cripple Creek" was derived. To keep out prospectors the cattle men laid off

the place into town lots, which they put on the market at $50 apiece, as a

prohibitory price. The prospectors gobbled up the lots and called for more.

From 1891 the district may be said to have a place in mining history, but

not until 1892 was the output sufficient to be recorded. Then it amounted to

$600,000. Following is a showing of the output for four years:

1892: FIRST YEAR'S GOLD OUTPUT, $600,000.

1893: SECOND YEAR'S GOLD OUTPUT, $2,100,000.

1894: THIRD YEAR'S GOLD OUTPUT, $3,000,000

1895 FOURTH YEAR'S GOLD OUTPUT, $8,000,000.

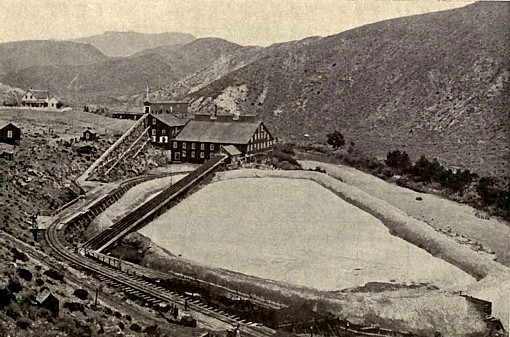

That diagram is a pictorial history of Cripple Creek. Its details would make

a book. The history of one of the score of hills in the district an area six

miles by ten in extent is the history of all the hills. It is a story of

pluck and luck and providence. Here is a typical tale told of the Portland

gold mine, one of the most valuable in Colorado as it was written by a staff

correspondent of the Chicago Tribune. It is a story to make your blood

tingle: "Another of the pitiful stories of the camp that partakes of the

nature of a romance is that of the Portland group. It is a tale of a minimum

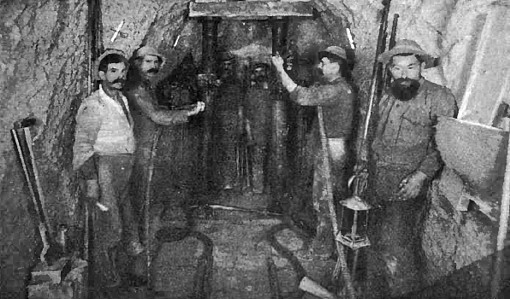

of luck mixed with a maximum of pluck and perseverance young men, James

Burns, James Doyle and John Harnan, all poor and living at Colorado Springs.

Burns was probably the most fortunate of the trio because he had learned the

plumbers' trade, and he had had some experience in working about mines in

Leadville and other places. By means of grubstakes and a little money earned

at odd times they had spent some time in prospecting. "One day they came

across rich

gold ore in the Portland, so called because two of them came

from that Maine city, and they saw fortunes ahead. But they had only a

fraction of a claim less than one-sixth of an acre and they realized that

they must get more ground if they were to be genuine bonanza kings. The ore

developed unexpected richness and they determined to secretly take out

enough to buy out their neighbors. Above all they must not excite the

suspicions of the wary prospectors who surrounded them. The story of how

they packed the rich stuff out of their mine at night on their backs has

often been told. They toiled incessantly, but the weary climb up the steep

hill tired them after a time, and they decided to try the experiment of

getting a wagon to haul away the mineral that was bringing in such handsome

returns, even though they were taking it out in such small quantities. On

the first trip the wagon broke down within a short distance of the shaft,

and in the morning the early prospectors were astonished at the sight of it

perched high on the side of Butte Mountain, where there was no road.

Curiosity excited, it was not long before they had satisfied themselves

where the ore came from. To trace the wheel tracks to the Portland dump was

easy.

"Then ensued a scramble for locations that lapped and overlapped the poor little Portland fraction to a discouraging degree. But the trio did not lose heart. They knew that with time they could get enough money out of their mine to make the legal fights that came down like an avalanche. So they industriously worked away with forty-seven law suits hanging over their heads. Some they fought to a successful finish, others they compromised, and it all ended in their getting possession of 130 acres of patented land immediately surrounding their original location. And the money with which to prosecute these expensive suits, with the best Colorado legal talent employed on both sides, came out of the hole of which it was sought to deprive them. "Arrayed against them were such men as D. H. Moffatt, with the influence of millions in his hands, and other enormously rich persons. Throughout the long fights in the courts discouraging obstacles not originally counted upon were thrown in their way. One of these was the great strike of '93, and it came near making dough of their cake. They had agreed to buy one of the Moffatt adverse claims and had $285,000 to pay in a few weeks. The strike was declared in opposition to a demand made by certain mine owners that the miners work nine hours a day instead of eight. The conflict, with its dynamite and militia episodes, continued for months, but through the bull-dog determination of 'Jimmie' Burns the Portland continued to take out ore.

"The miners were given everything they wanted and more too in fact, anything to keep the hoisters going. When the day of settlement came Mr. Moffatt and his friends were given a check for the quarter of a million or more, and every cent of it had been taken out of the ground in dispute. It was one of the most remarkable transactions known to mining. "After that progress was easy, though before all the troubles of the trio were over J. R. McKinnie and Stratton, of the Independence, found their way into the company and gave it strength. All the fights, however, were not in the courts. Burns and Doyle, who kept guard over the property with their own eyes, were often obliged to sally out with shotguns and rifles and drive away would-be jumpers and contestants who thought 'possession was nine points in law,' and tried to gain that coin of vantage by force. "Not fifty feet from the main office of the Portland, on the mountain, Burns one night drove away six armed men who had started to sink a shaft. There were profane words and many threats, but the intruders finally withdrew with the promise of coming again. The gaping mouth of Burns' weapon accelerated their movements down the hill. When it was all over Burns discovered his rifle was not loaded. He felt much like the fainting woman who collapses when the danger is over. His hair has silvered in four years. Yet 'Jimmie' Burns is still a young man."

Return

to The Colorado History Page:

Colorado Gold Rush History