The Black Hills rise up abruptly and alone in the midst of a plain more than two hundred miles from any other range of mountains, their highest peaks reaching about seven thousand feet above sea level. To these mountains the Sioux Indians gave the name of "Pah Sappa," which, interpreted, is Black Hill. These are the Black Hills proper. They might truly be called an oasis in a wide and dreary desert, its approaches on every side being through long stretches of treeless plains, whose waters are so strongly impregnated with alkalies as to be unfit for the use of man. But when once the hills are reached, all this is changed. Dense forests abound ; springs and streams of pure water are abundant, and along the creek bottom-lands grows luxuriant grass. The soil of the valleys is rich and fertile, and it will become a fine grazing country. The following are said to have been the causes which led to the discoveries in this region. Some Indians came into a frontier trading post, bringing small grains and gold nuggets. Plied with presents and "fire-water," they said it came from the Black Hills. Other accounts of the discoveries in the Black Hills say that as far back as 1849, Indians exhibited specimens of native gold to trappers and hunters, which they claimed to have found in the Hills. It appears that as early as 1855, General Harney visited the Hills on a sort of an exploring expedition, and the highest peak has been named in his honor (Harney's Peak). General Warren visited them in 1856-57; Dr. Hayden in 1858-59, and General Sully in 1864. Father Desmet, a Catholic missionary, after whom the Desmet Gold Mine was named, also visited the Black Hills at a very early day. From the reports and observations of these many explorers it seems that the Hills were believed to contain great mineral wealth, although but little had been accomplished in the way of discovery. It is asserted that in 1852 a party of men, en route for California, influenced by reports of gold in the Black Hills, made their way thither, and found rich diggings ; but that they were all massacred by Indians except one, who made his escape, but died soon afterward of disease.

It seems some evidences tending to confirm this report have been found in the remains of old rotten and decayed sluice-boxes, and marks of mining works found there at the time of the great rush in 1876-77. These rumors spread, and becoming greatly exaggerated, all classes were excited by them. To solve the problem, the Government sent out Custer's expedition, of 1874. After his return, the question still being undecided, the expedition of 1875, under the charge of Professor Jenney, was ordered by the Interior Department, at Washington, of which some account has been given. This expedition found gold in many places, but no placer fields of very great richness; in fact, none that would pay the ordinary pan or cradle miner. The position of the present rich gold quartz mines in the vicinity of Deadwood was still undiscovered.

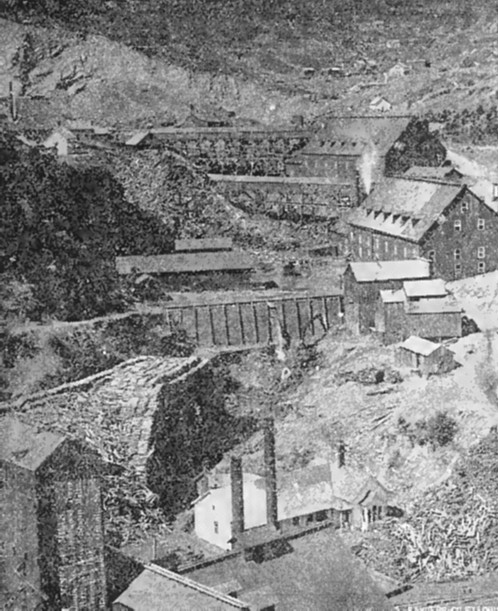

Professor Jenney did not visit Deadwood and Whitewood Gulches, owing to the dense forests and timber which presented obstacles to his entering with his train. In 1876, these gulches were prospected by miners and found to be rich in placer deposits. During that summer the population was swelled by a gold rush immigration of nearly seven thousand prospectors, who settled in and around Deadwood Gulch, and the yield of gold during the year, from the placer mines alone, was one and a half millions of dollars. Quartz mining was not yet at this time inaugurated.

Just previous, however, to the advent of Professor Jenney, and during the winter of 1874-75, a party of miners, consisting of twenty-two men and one woman, made their way into the Hills by following the trail by which General Custer came out in '74, and camped on French Creek, at a place since known as Camp Harney. Here they erected a stockade of upright logs, set two feet in the ground and rising twelve or fourteen feet high. This was made eighty feet square, with flanking projections at the corners, of very straight logs, ten inches in diameter, set as close together as possible and battened on the inside. There was but one gate, and that was on a side difficult to approach, on account of the creek, and was barred by a bullet-proof door. Inside this enclosure was five log cabins, and between the cabins and wall a space sufficient for their wagons and animals. These miners had also laid out a town, and the foundations of several houses were begun. This party, after all this labor had been expended by them, were compelled to leave, and were brought out of the Hills by troops about March 1st, 1875. They had been there but four months, yet in that short time, in addition to building the stockade, had riddled the valley with prospect holes and had worked on quartz leads in places far into the Hills. These were the first miners who ever wintered in the Black Hills, of which there is any reliable record. The fortress made by them has been called Tallant's Stockade, from Colonel D. G. Tallant, who is thought to have been the leader of the party, and his wife, Mrs. Tallant, being the first woman to enter the Black Hills.

Evidences of Former

Occupation.

This party claimed to have found evidences of former occupation by white

men. In the bed of the creek was found the rotten remains of cottonwood

trees, of which the heart had been hollowed out to form sluice-boxes. They

found the remains of two shovels, pieces of tin and fragments of iron not

far from the decayed sluices. They also claimed to have found the remains of

an old cabin, formed by poles leaning up against an overhanging rock, and

not far away a wooden cross, standing upright on a rock, tied together with

rawhide, and near its base, cut into the moss covered stone, were two rude

letters, "J. M.," and the date, "1846." This was supposed by Tallant to

mark the grave of some unfortunate pioneer. How reliable these stories may

be, the author has no means of ascertaining, but gives them for what they

are worth.

By the 20th of July, 1875, during the stay of the Government expedition, at least six hundred miners were engaged in mining and prospecting. As this part of country was then an Indian reservation, the Government desired that the miners should be taken out, and accordingly General Crook came in person to Custer City, called a meeting of miners, to take place August l0th, 1875, and requested them to voluntarily leave the Hills. He conversed freely with them and urged them to depart, making known to the miners that his orders were imperative to remove them from the Indian reservation.

Return

to The South Dakota Page:

South Dakota Gold Rush History