| Twain's great goal in prospecting was to really strike it rich. In

this episode of his life, he came very, very close to it. One has to wonder what might

have happened if Twain and his partner Higbie would have truly struck it rich. The Wide

west did go on to become a very successful and productive mine. Mark Twain only got into

writing because he was destitute as a prospector and really had no other viable choice.

Had he succeeded at mining, would we have lost one of America's greatest authors?

-----------    ------------

------------

I now come to a curious episode - the most curious, I think, that had yet accented my

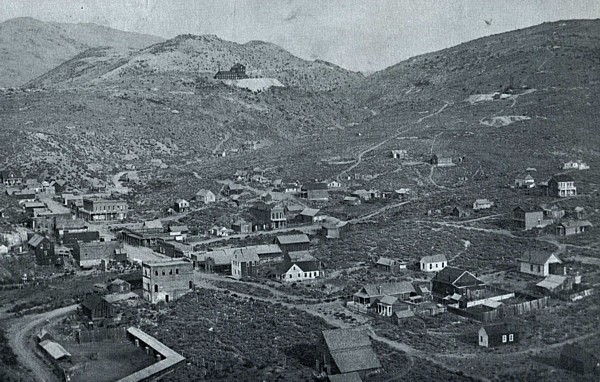

slothful, valueless, heedless career. Out of a hillside toward the upper end of the town,

projected a wall of reddish-looking quartz croppings, the exposed comb of a silver-bearing

ledge that extended deep down into the earth, of course. It was owned by a company

entitled the "Wide West." There was a shaft sixty or seventy feet deep on the

under side of the croppings, and everybody was acquainted with the rock that came from it

- and tolerably rich rock it was, too, but nothing extraordinary. I will remark here, that

although to the inexperienced stranger all the quartz of a particular "district"

looks about alike, an old resident of the camp can take a glance at a mixed pile of rock,

separate the fragments and tell you which mine each came from, as easily as a confectioner

can separate and classify the various kinds and qualities of candy in a mixed heap of the

article.

All at once the town was thrown into a state of extraordinary excitement. In mining

parlance the Wide West had "struck it rich!" Everybody went to see the new

developments, and for some days there was such a crowd of people about the Wide West shaft

that a stranger would have supposed there was a mass-meeting in session there. No other

topic was discussed but the rich strike, and nobody thought or dreamed about anything

else. Every man brought away a specimen, ground it up in a hand-mortar, washed it out in

his horn spoon, and glared speechless upon the marvelous result. It was not hard rock, but

black, decomposed stuff which could be crumbled in the hand like a baked potato, and when

spread out on a paper exhibited a thick sprinkling of gold and particles of

"native" silver. Higbie brought a handful to the cabin, and when he had washed

it out his amazement was beyond description. Wide West stock soared skyward. It was said

that repeated offers had been made for it at a thousand dollars a foot, and promptly

refused. We have all had the "blues" - the mere skyblues - but mine were indigo,

now - because I did not own in the Wide West. The world seemed hollow to me, and existence

a grief. I lost my appetite, and ceased to take an interest in anything. Still I had to

stay, and listen to other people's rejoicings, because I had no money to get out of the

camp with.

The Wide West company put a stop to the carrying away of "specimens," and well

they might, for every handful of the ore was worth a sum of some consequence. To show the

exceeding value of the ore, I will remark that a sixteen-hundred-pounds parcel of it was

sold, just as it lay, at the mouth of the shaft, at one dollar a pound; and the man who

bought it "packed" it on mules a hundred and fifty or two hundred miles, over

the mountains, to San Francisco, satisfied that it would yield at a rate that would richly

compensate him for his trouble. The Wide West people also commanded their foreman to

refuse any but their own operatives permission to enter the mine at any time or for any

purpose. I kept up my "blue" meditations and Higbie kept up a deal of thinking,

too, but of a different sort. He puzzled over the "rock," examined it with a

glass, inspected it in different lights and from different points of view, and after each

experiment delivered himself, in soliloquy, of one and the same unvarying opinion in the

same unvarying formula:

"It is not Wide West rock!"

He said once or twice that he meant to have a look into the Wide West shaft if he got shot

for it. I was wretched, and did not care whether he got a look into it or not. He failed

that day, and tried again at night; failed again; got up at dawn and tried, and failed

again. Then he lay in ambush in the sage-brush hour after hour, waiting for the two or

three hands to adjourn to the shade of a boulder for dinner; made a start once, but was

premature - one of the men came back for something; tried it again, but when almost at the

mouth of the shaft, another of the men rose up from behind the boulder as if to

reconnoitre, and he dropped on the ground and lay quiet; presently he crawled on his hands

and knees to the mouth of the shaft, gave a quick glance around, then seized the rope and

slid down the shaft. He disappeared in the gloom of a "side drift" just as a

head appeared in the mouth of the shaft and somebody shouted "Hello!" - which he

did not answer. He was not disturbed any more. An hour later he entered the cabin, hot,

red, and ready to burst with smothered excitement, and exclaimed in a stage whisper:

"I knew it! We are rich! It's a blind lead!"

I thought the very earth reeled under me. Doubt - conviction - doubt again - exultation -

hope, amazement, belief, unbelief - every emotion imaginable swept in wild procession

through my heart and brain, and I could not speak a word. After a moment or two of this

mental fury, I shook myself to rights, and said:

"Say it again!"

"It's a blind lead!"

"Cal, let's - let's burn the house - or kill somebody! Let's get out where there's

room to hurrah! But what is the use? It is a hundred times too good to be true."

"It's a blind lead for a million! - hanging wall - foot wall - clay casings -

everything complete!" He swung his hat and gave three cheers, and I cast doubt to the

winds and chimed in with a will. For I was worth a million dollars, and did not care

"whether school kept or not!"

But perhaps I ought to explain. A "blind lead" is a lead or ledge that does not

"crop out" above the surface. A miner does not know where to look for such

leads, but they are often stumbled upon by accident in the course of driving a tunnel or

sinking a shaft. Higbie knew the Wide West rock perfectly well, and the more he had

examined the new developments the more he was satisfied that the ore could not have come

from the Wide West vein. And so had it occurred to him alone, of all the camp, that there

was a blind lead down in the shaft, and that even the Wide West people themselves did not

suspect it. He was right. When he went down the shaft, he found that the blind lead held

its independent way through the Wide West vein, cutting it diagonally, and that it was

inclosed in its own well-defined casing-rocks and clay. Hence it was public property. Both

leads being perfectly well defined, it was easy for any miner to see which one belonged to

the Wide West and which did not.

We thought it well to have a strong friend, and therefore we brought the foreman of the

Wide West to our cabin that night and revealed the great surprise to him. Higbie said:

"We are going to take possession of this blind lead, record it and establish

ownership, and then forbid the Wide West company to take out any more of the rock. You

cannot help your company in this matter - nobody can help them. I will go into the shaft

with you and prove to your entire satisfaction that it is a blind lead. Now we propose to

take you in with us, and claim the blind lead in our three names. What do you say?"

What could a man say who had an opportunity to simply stretch forth his hand and take

possession of a fortune without risk of any kind and without wronging any one or attaching

the least taint of dishonor to his name? He could only say, "Agreed."

The notice was put up that night, and duly spread upon the recorder's books before ten

o'clock. We claimed two hundred feet each - six hundred feet in all - the smallest and

compactest organization in the district, and the easiest to manage.

No one can be so thoughtless as to suppose that we slept that night. Higbie and I went to

bed at midnight, but it was only to lie broad awake and think, dream, scheme. The

floorless, tumble-down cabin was a palace, the ragged gray blankets silk, the furniture

rosewood and mahogany. Each new splendor that burst out of my visions of the future

whirled me bodily over in bed or jerked me to a sitting posture just as if an electric

battery had been applied to me. We shot fragments of conversation back and forth at each

other. Once Higbie said:

"When are you going home - to the States?"

"To-morrow!" - with an evolution or two, ending with a sitting position.

"Well - no - but next month, at furthest."

"We'll go in the same steamer."

"Agreed."

A pause.

"Steamer of the 10th?"

"Yes. No, the 1st."

"All right."

Another pause.

"Where are you going to live?" said Higbie.

"San Francisco."

"That's me!"

Pause.

"Too high - too much climbing" - from Higbie.

"What is?"

"I was thinking of Russian Hill - building a house up there."

"Too much climbing? Sha'n't you keep a carriage?"

"Of course. I forgot that."

Pause.

"Cal, what kind of a house are you going to build?"

"I was thinking about that. Three-story and an attic."

"But what kind?"

"Well, I don't hardly know. Brick, I suppose."

"Brick - bosh."

"Why? What is your idea?"

"Brown-stone front - French plate-glass - billiard-room off the dining-room -

statuary and paintings - shrubbery and two-acre grass-plat - greenhouse - iron dog on the

front stoop - gray horses - landau, and a coachman with a bug on his hat!"

"By George!"

A long pause.

"Cal, when are you going to Europe?"

"Well - I hadn't thought of that. When are you?"

"In the spring."

"Going to be gone all summer?"

"All summer! I shall remain there three years."

"No - but are you in earnest?"

"Indeed I am."

"I will go along too."

"Why, of course you will."

"What part of Europe shall you go to?"

"All parts. France, England, Germany - Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Syria, Greece,

Palestine, Arabia, Persia, Egypt - all over - everywhere."

"I'm agreed."

"All right."

"Won't it be a swell trip!"

"We'll spend forty or fifty thousand dollars trying to make it one, anyway."

Another long pause.

"Higbie, we owe the butcher six dollars, and he has been threatening to stop our -

"

"Hang the butcher!"

"Amen."

|

.-g.-. |

|

And so it

went on. By three o'clock we found it was no use, and so we got up and played cribbage and

smoked pipes till sunrise. It was my week to cook. I always hated cooking - now, I

abhorred it.

The news was all over town. The former excitement was great - this one was greater still.

I walked the streets serene and happy. Higbie said the foreman had been offered two

hundred thousand dollars for his third of the mine. I said I would like to see myself

selling for any such price. My ideas were lofty. My figure was a million. Still, I

honestly believe that if I had been offered it, it would have had no other effect than to

make me hold off for more.

I found abundant enjoyment in being rich. A man offered me a three-hundred-dollar horse,

and wanted to take my simple, unindorsed note for it. That brought the most realizing

sense I had yet had that I was actually rich, beyond shadow of doubt. It was followed by

numerous other evidences of a similar nature - among which I may mention the fact of the

butcher leaving us a double supply of meat and saying nothing about money.

By the laws of the district, the "locators" or claimants of a ledge were obliged

to do a fair and reasonable amount of work on their new property within ten days after the

date of the location, or the property was forfeited, and anybody could go and seize it

that chose. So we determined to go to work the next day. About the middle of the

afternoon, as I was coming out of the post-office, I met a Mr. Gardiner, who told me that

Capt. John Nye was lying dangerously ill at his place (the "Nine-Mile Ranch"),

and that he and his wife were not able to give him nearly as much care and attention as

his case demanded. I said if he would wait for me a moment, I would go down and help in

the sickroom. I ran to the cabin to tell Higbie. He was not there, but I left a note on

the table for him, and a few minutes later I left town in Gardiner's wagon.

Captain Nye was very ill indeed, with spasmodic rheumatism. But the old gentleman was

himself - which is to say, he was kind-hearted and agreeable when comfortable, but a

singularly violent wildcat when things did not go well. He would be smiling along

pleasantly enough, when a sudden spasm of his disease would take him and he would go out

of his smile into a perfect fury. He would groan and wail and howl with the anguish, and

fill up the odd chinks with the most elaborate profanity that strong convictions and a

fine fancy could contrive. With fair opportunity he could swear very well and handle his

adjectives with considerable judgment; but when the spasm was on him it was painful to

listen to him, he was so awkward. However, I had seen him nurse a sick man himself and put

up patiently with the inconveniences of the situation, and consequently I was willing that

he should have full license now that his own turn had come. He could not disturb me, with

all his raving and ranting, for my mind had work on hand, and it labored on diligently,

night and day, whether my hands were idle or employed. I was altering and amending the

plans for my house, and thinking over the propriety of having the billiard-room in the

attic, instead of on the same floor with the dining-room; also, I was trying to decide

between green and blue for the upholstery of the drawing-room, for, although my preference

was blue, I feared it was a color that would be too easily damaged by dust and sunlight;

likewise while I was content to put the coachman in a modest livery, I was uncertain about

a footman - I needed one, and was even resolved to have one, but wished he could properly

appear and perform his functions out of livery, for I somewhat dreaded so much show; and

yet, inasmuch as my late grandfather had had a coachman and such things, but no liveries,

I felt rather drawn to beat him; - or beat his ghost, at any rate; I was also

systematizing the European trip, and managed to get it all laid out, as to route and

length of time to be devoted to it - everything, with one exception - namely, whether to

cross the desert from Cairo to Jerusalem per camel, or go by sea to Beirut, and thence

down through the country per caravan. Meantime I was writing to the friends at home

every day, instructing them concerning all my plans and

intentions, and directing them to look up a handsome homestead for my mother and agree

upon a price for it against my coming, and also directing them to sell my share of the

Tennessee land and tender the proceeds to the widows' and orphans' fund of the

typographical union of which I had long been a member in good standing. [This Tennessee

land had been in the possession of the family many years, and promised to confer high

fortune upon us some day; it still promises it, but in a less violent way.]

When I had been nursing the captain nine days he was somewhat better, but very feeble.

During the afternoon we lifted him into a chair and gave him an alcoholic vapor bath, and

then set about putting him on the bed again. We had to be exceedingly careful, for the

least jar produced pain. Gardiner had his shoulders and I his legs; in an unfortunate

moment I stumbled and the patient fell heavily on the bed in an agony of torture. I never

heard a man swear so in my life. He raved like a maniac, and tried to snatch a revolver

from the table - but I got it. He ordered me out of the house, and swore a world of oaths

that he would kill me wherever he caught me when he got on his feet again. It was simply a

passing fury, and meant nothing. I knew he would forget it in an hour, and maybe be sorry

for it, too; but it angered me a little, at the moment. So much so, indeed, that I

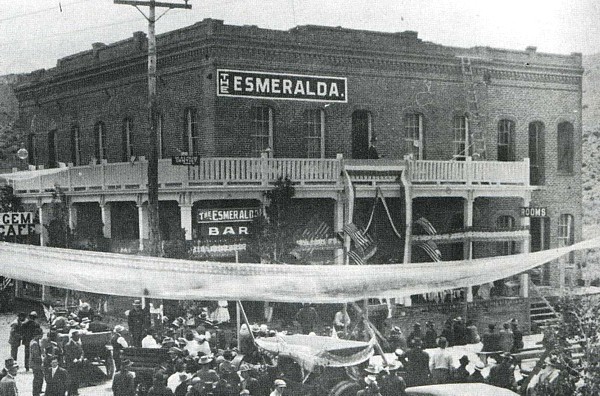

determined to go back to Esmeralda. I thought he was able to get along alone, now, since

he was on the war-path. I took supper, and as soon as the moon rose, began my nine-mile

journey, on foot. Even millionaires needed no horses, in those days, for a mere nine-mile

jaunt without baggage.

As I "raised the hill" overlooking the town, it lacked fifteen minutes of

twelve. I glanced at the hill over beyond the canon, and in the bright moonlight saw what

appeared to be about half the population of the village massed on and around the Wide West

croppings. My heart gave an exulting bound, and I said to myself, "They have made a

new strike to-night - and struck it richer than ever, no doubt." I started over

there, but gave it up. I said the "strike" would keep, and I had climbed hills

enough for one night. I went on down through the town, and as I was passing a little

German bakery, a woman ran out and begged me to come in and help her. She said her husband

had a fit. I went in, and judged she was right - he appeared to have a hundred of them,

compressed into one. Two Germans were there, trying to hold him, and not making much of a

success of it. I ran up the street half a block or so and routed out a sleeping doctor,

brought him down half dressed, and we four wrestled with the maniac, and doctored,

drenched and bled him, for more than an hour, and the poor German woman did the crying. He

grew quiet, now, and the doctor and I withdrew and left him to his friends.

It was a little after one o'clock. As I entered the cabin door, tired but jolly, the dingy

light of a tallow candle revealed Higbie, sitting by the pine table gazing stupidly at my

note, which he held in his fingers, and looking pale, old, and haggard. I halted, and

looked at him. He looked at me, stolidly. I said:

"Higbie, what - what is it?"

"We're ruined - we didn't do the work - The Blind Lead's Relocated!"

|

. |

|

It was

enough. I sat down sick, grieved - broken-hearted, indeed. A minute before, I was rich and

brimful of vanity; I was a pauper now, and very meek. We sat still an hour, busy with

thought, busy with vain and useless self-upbraidings, busy with "Why didn't I do

this, and why didn't I do that," but neither spoke a word. Then we dropped into

mutual explanations, and the mystery was cleared away. It came out that Higbie had

depended on me, as I had on him, and as both of us had on the foreman. The folly of it! It

was the first time that ever staid and steadfast Higbie had left an important matter to

chance or failed to be true to his full share of a responsibility.

But he had never seen my note till this moment, and this moment was the first time he had

been in the cabin since the day he had seen me last. He, also, had left a note for me, on

that same fatal afternoon - had ridden up on horseback, and looked through the window, and

being in a hurry and not seeing me, had tossed the note into the cabin through a broken

pane. Here it was, on the floor, where it had remained undisturbed for nine days:

Don't fail to do the work before the ten days expire. W. has passed through and given me

notice. I am to join him at Mono Lake, and we shall go on from there to-night. He says he

will find it this time, sure. Cal.

"W." meant Whiteman, of course. That thrice accursed "cement"!

That was the way of it. An old miner, like Higbie, could no more withstand the fascination

of a mysterious mining excitement like this "cement" foolishness, than he could

refrain from eating when he was famishing. Higbie had been dreaming about the marvelous

cement for months; and now, against his better judgment, he had gone off and "taken

the chances" on my keeping secure a mine worth a million undiscovered cement veins.

They had not been followed this time. His riding out of town in broad daylight was such a

commonplace thing to do that it had not attracted any attention. He said they prosecuted

their search in the fastnesses of the mountains during nine days, without success; they

could not find the cement. Then a ghastly fear came over him that something might have

happened to prevent the doing of the necessary work to hold the blind lead (though indeed

he thought such a thing hardly possible) and forthwith he started home with all speed. He

would have reached Esmeralda in time, but his horse broke down and he had to walk a great

part of the distance. And so it happened that as he came into Esmeralda by one road, I

entered it by another. His was the superior energy, however, for he went straight to the

Wide West, instead of turning aside as I had done - and he arrived there about five or ten

minutes too late! The "notice" was already up, the "relocation" of our

mine completed beyond recall, and the crowd rapidly dispersing. He learned some facts

before he left the ground. The foreman had not been seen about the streets since the night

we had located the mine - a telegram had called him to California on a matter of life and

death, it was said. At any rate he had done no work and the watchful eyes of the community

were taking note of the fact. At midnight of this woeful tenth day, the ledge would be

"relocatable," and by eleven o'clock the hill was black with men prepared to do

the relocating. That was the crowd I had seen when I fancied a new "strike" had

been made - idiot that I was. [We three had the same right to relocate the lead that other

people had, provided we were quick enough.] As midnight was announced, fourteen men, duly

armed and ready to back their proceedings, put up their "notice" and proclaimed

their ownership of the blind lead, under the new name of the "Johnson." But A.

D. Allen, our partner (the foreman), put in a sudden appearance about that time, with a

cocked revolver in his hand, and said his name must be added to the list, or he would

"thin out the Johnson company some." He was a manly, splendid, determined

fellow, and known to be as good as his word, and therefore a compromise was effected. They

put in his name for a hundred feet, reserving to themselves the customary two hundred feet

each. Such was the history of the night's events, as Higbie gathered from a friend on the

way home.

Higbie and I cleared out on a new mining excitement the next

morning, glad to get away from the scene of our sufferings, and after a month or two of

hardship and disappointment, returned to Esmeralda once more. Then we learned that the

Wide West and the Johnson companies had consolidated; that the stock, thus united,

comprised five thousand feet, or shares; that the foreman, apprehending tiresome

litigation, and considering such a huge concern unwieldy, had sold his hundred feet for

ninety thousand dollars in gold and gone home to the States to enjoy it. If the stock was

worth such a gallant figure, with five thousand shares in the corporation, it makes me

dizzy to think what it would have been worth with only our original six hundred in it. It

was the difference between six hundred men owning a house and five thousand owning it. We

would have been millionaires if we had only worked with pick and spade one little day on

our property and so secured our ownership!

It reads like a wild fancy sketch, but the evidence of many witnesses, and likewise that

of the official records of Esmeralda District, is easily obtainable in proof that it is a

true history. I can always have it to say that I was absolutely and unquestionably worth a

million dollars, once, for ten days.

A year ago my esteemed and in every way estimable old millionaire partner, Higbie, wrote

me from an obscure little mining - camp in California that after nine or ten years of

buffetings and hard striving, he was at last in a position where he could command

twenty-five hundred dollars, and said he meant to go into the fruit business in a modest

way. How such a thought would have insulted him the night we lay in our cabin planning

European trips and brown-stone houses on Russian Hill!

Mark Twain’s stories about his experiences prospecting in

the west, including many more humorous tales of his adventures can be found in his book:

ROUGHING IT |

. |

|