|

Mines Not worth Their "Salt" |

.

| Twain fit well

into the boom times of Virginia City in the 1860s. He had friends and took well to life as

a reporter for the Enterprise. The feet refered to in this story are stock shares of the

ownership in the claim - at the time it was prevalent to refer to the shares as feet

(undivided). As Twain notes, there was such wealth that stock shares were given without

hesitation. Here is his story: ----------- My salary was increased to forty dollars a week. But I seldom drew it. I had plenty of other resources, and what were two broad twenty-dollar gold pieces to a man who had his pockets full of such and a cumbersome abundance of bright half-dollars besides? [Paper money has never come into use on the Pacific coast.] Reporting was lucrative, and every man in the town was lavish with his money and his "feet." The city and all the great mountainside were riddled with mining-shafts. There were more mines than miners. True, not ten of these mines were yielding rock worth hauling to a mill, but everybody said, "Wait till the shaft gets down where the ledge comes in solid, and then you will see!" So nobody was discouraged. These were nearly all "wildcat" mines, and wholly worthless, but nobody believed it then. The "Ophir," the "Gould & Curry," the "Mexican," and other great mines on the Comstock lead in Virginia and Gold Hill were turning out huge piles of rich rock every day, and every man believed that his little wildcat claim was as good as any on the "main lead" and would infallibly be worth a thousand dollars a foot when he "got down where it came in solid." Poor fellow! he was blessedly blind to the fact that he never would see that day. So the thousand wildcat shafts burrowed deeper and deeper into the earth day by day, and all men were beside themselves with hope and happiness. How they labored, prophesied, exulted! Surely nothing like it was ever seen before since the world began. Every one of these wildcat mines - not mines, but holes in the ground over imaginary mines - was incorporated and had handsomely engraved "stock" and the stock was salable too. It was bought and sold with a feverish avidity in the boards every day. You could go up on the mountainside, scratch around and find a ledge (there was no lack of them), put up a "notice" with a grandiloquent name on it, start a shaft, get your stock printed, and with nothing whatever to prove that your mine was worth a straw, you could put your stock on the market and sell out for hundreds and even thousands of dollars. To make money, and make it fast, was as easy as it was to eat your dinner. Every man owned "feet" in fifty different wildcat mines and considered his fortune made. Think of a city with not one solitary poor man in it! One would suppose that when month after month went by and still not a wildcat mine (by wildcat I mean, in general terms, any claim not located on the mother vein, i.e., the "Comstock") yielded a ton of rock worth crushing, the people would begin to wonder if they were not putting too much faith in their prospective riches; but there was not a thought of such a thing. They burrowed away, bought and sold, and were happy. New claims were taken daily, and it was the friendly custom to run straight to the newspaper offices, give the reporter forty or fifty "feet," and get him to go and examine the mine and publish a notice of it. They did not care a fig what you said about the property so you said something. Consequently we generally said a word or two to the effect that the "indications" were good, or that the ledge was "six feet wide," or that the rock "resembled the Comstock" (and so it did - but as a general thing the resemblance was not startling enough to knock you down). If the rock was moderately promising, we followed the custom of the country, used strong adjectives and frothed at the mouth as if a very marvel in silver discoveries had transpired. If the mine was a "developed" one, and had no pay-ore to show (and of course it hadn't), we praised the tunnel; said it was one of the most infatuating tunnels in the land; driveled and driveled about the tunnel till we ran entirely out of ecstasies - but never said a word about the rock. We would squander half a column of adulation on a shaft, or a new wire rope, or a dressed-pine windlass, or a fascinating force-pump, and close with a burst of admiration of the "gentlemanly and efficient superintendent" of the mine - but never utter a whisper about the rock. And those people were always pleased, always satisfied. Occasionally we patched up and varnished our reputation for discrimination and stern, undeviating accuracy, by giving some old abandoned claim a blast that ought to have made its dry bones rattle - and then somebody would seize it and sell it on the fleeting notoriety thus conferred upon it. |

.-g.-. | |

There was

nothing in the shape of a mining claim that was not salable. We received presents of

"feet" every day. If we needed a hundred dollars or so, we sold some; if not, we

hoarded it away, satisfied that it would ultimately be worth a thousand dollars a foot. I

had a trunk about half full of "stock." When a claim made a stir in the market

and went up to a high figure, I searched through my pile to see if I had any of its stock

- and generally found it. |

. | |

To show what a wild spirit possessed the mining brain of the community, I will remark that "claims" were actually "located" in excavations for cellars, where the pick had exposed what seemed to be quartz veins - and not cellars in the suburbs, either, but in the very heart of the city; and forthwith stock would be issued and thrown on the market. It was small matter who the cellar belonged to - the "ledge" belonged to the finder, and unless the United States Government interfered (inasmuch as the government holds the primary right to mines of the noble metals in Nevada - or at least did then), it was considered to be his privilege to work it. Imagine a stranger staking out a mining claim among the costly shrubbery in your front yard and calmly proceeding to lay waste the ground with pick and shovel and blasting-powder! It has been often done in California. In the middle of one of the principal business streets of Virginia, a man "located" a mining claim and began a shaft on it. He gave me a hundred feet of the stock and I sold it for a fine suit of clothes because I was afraid somebody would fall down the shaft and sue for damages. I owned in another claim that was located in the middle of another street; and to show how absurd people can be, that "East India" stock (as it was called) sold briskly although there was an ancient tunnel running directly under the claim and any man could go into it and see that it did not cut a quartz ledge or anything that remotely resembled one. One plan

of acquiring sudden wealth was to "salt" a wildcat claim and sell out while the

excitement was up. The process was simple. The schemer located a worthless ledge, sunk a

shaft on it, bought a wagon-load of rich "Comstock" ore, dumped a portion of it

into the shaft and piled the rest by its side above-ground. Then he showed the property to

a simpleton and sold it to him at a high figure. Of course the wagon-load of rich ore was

all that the victim ever got out of his purchase. A most remarkable case of

"salting" was that of the "North Ophir." It was claimed that this vein

was a remote "extension" of the original "Ophir," a valuable mine on

the "Comstock." For a few days everybody was talking about the rich developments

in the North Ophir. It was said that it yielded perfectly pure silver in small, solid

lumps. I went to the place with the owners, and found a shaft six or eight feet deep, in the bottom of which was a badly shattered vein of dull,

yellowish, unpromising rock. One would as soon expect to find silver in a grindstone. We

got out a pan of the rubbish and washed it in a puddle, and sure enough, among the

sediment we found half a dozen black, bullet-looking pellets of unimpeachable

"native" silver. Nobody had ever heard of such a thing before; science could not

account for such a queer novelty. The stock rose to sixty-five dollars a foot, and at this

figure the world-renowned tragedian, McKean Buchanan, bought a commanding interest and

prepared to quit the stage once more - he was always doing that. And then it transpired

that the mine had been "salted" - and not in any hackneyed way, either, but in a

singularly bold, barefaced and peculiarly original and outrageous fashion. On one of the

lumps of "native" silver was discovered the minted legend, "Ted States

Of," and then it was plainly apparent that the mine had been "salted" with

melted half-dollars! The lumps thus obtained had been blackened till they resembled native

silver, and were then mixed with the shattered rock in the bottom of the shaft. It is

literally true. Of course the price of the stock at once fell to nothing, and the

tragedian was ruined. But for this calamity we might have lost McKean Buchanan from the

stage. Mark Twain’s stories about his experiences prospecting in

the west, including many more humorous tales of his adventures can be found in his book: ROUGHING IT |

. |

.

|

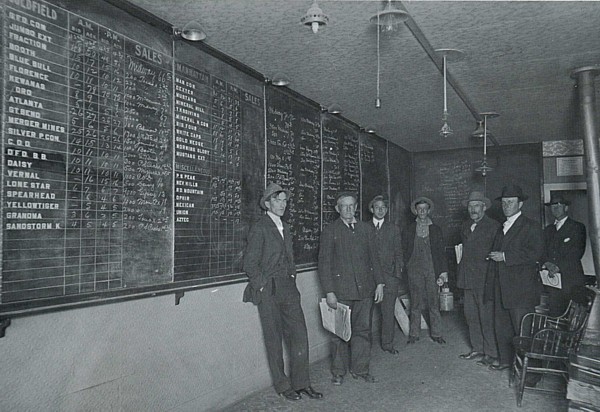

Stock shares (feet) in mines were bought and sold continually in small brokerages shops and on exchanges. The stock market shot shows the old time way of selling shares and keeping track on a chalk board. |

|

Mines were set up to be sold almost as soon as holes could be dug and samples for assay taken. |

Please note that the author, Chris Ralph, retains all copyrights to this entire document

and it may not be reproduced, quoted or copied without permission.

About OUR Nevada Turquoise

All of the turquoise sold on this site is mined from our own mines in Nevada. No one can offer a stronger assurance of the origin and natural nature of gem turquoise than we can for our turquoise - after all we are the ones who pulled it from the ground. We offer a free virtual tour of our mines, so you can see the real "Nevada Outback" conditions where our turquoise originated. Come a see what mining turquoise in Nevada is all about - CLICK HERE.