The following is another, more complete and accurate account of the Chilean “war” at Mokolumne during the gold rush, written by one who was a part of it:

My narrative now brings me to one of the most tragic episodes that ever occurred in the mines, and as it has so far escaped a place in written California history, I will give a faithful account of the lamentable event. Situated on an elevated flat, about two miles from our camp, was a settlement of Chilean miners. One Dr. Concha was the chief and moving spirit in this settlement, supported by some eight or ten lieutenants. The rest of the people consisted of peons whom they had brought from Chile, and who stood in relation to the headmen as dependents, in fact as slaves. Small parties of Americans complained that whenever they discovered a new gulch and attempted to mine in it, they were driven off by a superior body of these Chileans who laid claim to the gulch. At last the action of the Chileans became unendurable, and unless steps were taken to counteract their pretensions they might result in actual hostility and bloodshed. A mass meeting was called of the miners of the district. This meeting decided to adopt a code of laws, under which the size, location and possession of claims would be regularly determined.

In other mining districts where Americans from the South had brought their slaves with them, a law was adopted which prohibited the masters from taking up claims for their slaves. The same principle applied to the Chileans would prohibit them from the right to take up claims for their peons. The district was organized at this meeting, its boundaries set forth, and a code of mining laws, in which the above principles were included, was adopted.

It was not long after this meeting had been held when some of our miners were driven by force, and under peculiarly aggravating circumstances, out of a gulch they had been working in. When news of this exasperating aggression reached the various camps in the district, the excitement was intense. We had, as was usual at that time in the mines, elected an alcalde, before whom all classes of disputes were settled, and whose decisions were invariably acquiesced in and enforced. Judge Collier, of Virginia, a venerable gentleman of distinguished presence, of large intelligence and of positive character backed by unflinching nerve, had been selected. Complaint was made before him of this last aggression, and he advised that a mass meeting of the miners of the district should be called. This meeting came together in a temper of great exasperation against the Chileans, and adopted a resolution to rid the district of these unpleasant neighbors by fixing a time at which they should leave, and if they refused, then to forcibly expel them. The meeting marched in a body to Chilean Camp, and served the notice upon the headmen present.

The Chilean imbroglio had almost passed out of our mind, when, one evening a few weeks later at about eight o'clock, our attention was attracted by a sound as of marching men. Suddenly our tent flaps were thrown aside and a dozen guns were pointed at us. We were ordered to come outside, and each one as he reached the door was seized and his arms bound together behind with cords. Four of us were fastened to a tree, and a strong guard placed over us. There was such flourishing of pistols and knives that I feared some of us would be killed by accident if not design, if these fellows were not compelled to keep quiet. I spoke to the man in command in Spanish, and told him there was no need of these tumultuous demonstrations ; we were their prisoners, and would not attempt to escape. My speech had the desired effect, and I found my captor rather communicative. The rest of the band, in the meantime, had seized and bound the Americans in the Iowa Cabins and in several tents near by. Shortly afterwards a messenger told my captor to come to the camp on the hill, and bring me with him, as I might be wanted as an interpreter. This camp was located on a hill about half a mile from ours. On arriving at the foot of the hill we were instructed to wait for further orders. We had not been long waiting before we heard several shots fired in quick succession. I turned to my guard and told him this was a very bad business, and that if any of our people were killed they would be held to a severe account for it. About this time we were called to come to the camp.

On reaching it I found an old man named Endicott in the last agony from gunshot wounds, and near him was another old man named Starr who had been severely wounded in the right arm and shoulder. These were the only white men they found in the camp; for the others had gone off on a visit to other camps. The leader of the Chileans was called "Tirante," and he was not misnamed. He seemed to gloat over the body of poor Endicott, and calling me to him, asked me if that was not Judge Collier. When I assured him it was not he seemed greatly disappointed. Judge Collier was looked upon by the Chileans as the instigator and inciter of the American miners against them, and they wanted to wreak vengeance upon him above all others. A short consultation ensued between Tirante and his chief men as to the next move they should make. They feared that information about their movements might reach the camp where Judge Collier lived. As it was a considerable camp, it was probable, if the alarm were given that an armed force would soon confront them, so they determined to return to the Iowa Cabins, and with their prisoners move forward.

Although Starr was in great pain, he was ordered to march with us. With the assistance I rendered him he succeeded in reaching the Iowa Cabins, where our captors held a consultation, and determined to proceed to the south fork of the Calaveras. Starr was to be left behind, and I placed him in a bunk, wrapping him up as comfortably as I could. He was afterwards found dead in the bunk, and as I did not think that the wounds he had received on the hill were mortal, I have always believed that the Chileans dispatched him before they left. They would have reasoned that he might manage to crawl to the lower camp, give the alarm and cause an armed force to be sent against them, and that therefore the best way would be to finish him at once.As we marched along I was enabled to see that the Chileans numbered about sixty, whilst we were thirteen captives. They were very careful to see that our arms were securely bound behind us. They marched us to the south fork of the Calaveras, near a trading store kept by Scollan, Alburger & Co. John Scollan was a regularly appointed alcalde. He had come to California with Stevenson's regiment and the firm had stores at various points in the southern mines. Several of the Chilean leaders proceeded to the store, and I learned afterwards that they tried hard to get Judge Scollan to give a tone of legality to their murderous proceedings by certifying to our arrest by the authority of a warrant that had been issued by Judge Reynolds, of Stockton, Judge of the Fifth Instance. It seems that Dr. Concha had gone to Stockton and secured such a writ from Judge Reynolds, and then prevailed upon the latter and his Sheriff, whose name I have forgotten, to authorize his people to serve it. Alcade Scollan refused to have anything to do with the affair. He advised them to release their prisoners at once, and told them they would be held criminally responsible for their acts. Some of these facts I learned long afterwards. John Scollan died in Santa Barbara in 1892. He had been for many years a much respected citizen of that county, and he and I have often recalled the incidents of that eventful night in December, 1949, at the South Fork of the Calaveras.

Tirante and the rest came back to where they had left us, and in a manifestly dissatisfied mood countermarched us until we struck the trail up Chile Gulch in the direction of their own camp, which we reached about daylight. Here was another long wait. When the leaders returned from their camp some of them were mounted. We pushed forward until we struck the main road to Stockton. When we got to Frank Lemons' tent at the lower crossing of the Calaveras we were allowed to get some coffee and food. Mr. Rainer happened to be there, and we gave him an account of the whole affair. He was greatly wrought up about it, and said he would ride into Stockton and bring out a rescuing party. Rainer was a brave, but rash, impetuous man, and we warned him to act prudently, for we feared that our captors might, if they thought they were to be attacked by a superior force, end the matter by killing their prisoners and scattering. The warning was timely, but unfortunately was not heeded, for soon afterwards, as we passed Douglass & Rainer's ranch, we could see Rainer and several others loading their guns in full sight of our wary captors, who lost no time in taking us away from the main road, and marching us across the plains, which were densely covered with wild oats and tar weed. We could see, by the movements of the Chileans and the earnest whisperings of their chiefs, that they were not at all at their ease. They acted like men who felt that they might at any moment be confronted with most serious difficulties. I also noticed that they had diminished in numbers considerably. Some of the peons had dropped out from sheer exhaustion; others had furtively deserted. Whenever we would come within sight of the main road, there were signs of a commotion. Either a horseman, fully equipped with arms, would ride furiously in the direction of Stockton ; or men would be seen in covert places as if reconnoitering. It was late in the afternoon ; the rain had been coming down in intermittent showers ; Tirante and his lieutenants had had earnest and animated interviews as they grouped together on the march; we had come to a spot near the Mokelumne river where a grove of large, wide-spreading oaks afforded shelter from the weather, and here we were halted and lined up against a fallen tree. We had not been long here before a couple of mounted Chileans, who had been sent out as scouts, rode up. I was near enough to catch scattered words of their report, which was to the effect that there was an armed party on the road in quest of us. A most intensely dramatic scene followed their report. Tirante proposed that the prisoners be dispatched, after which they would disperse. He was supported in this terrible proposition by several voices; but a large, fine-looking Chilean called Maturano, who on several occasions had protested against the violent methods of Tirante, opposed the proposition not only as cruel and inhuman, but as one that would surely bring upon them the vengeance of the whole American people. The question was debated between the chiefs for some time, when it was put to vote, and Tirante's blood-thirsty proposal was lost.

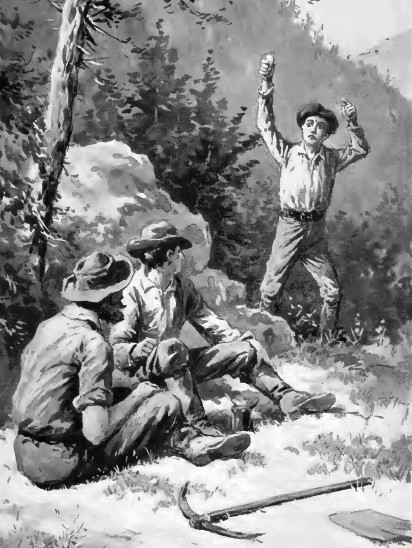

The reader can well imagine that I felt greatly relieved at the result, and I made up my mind that if it ever lay in my power I would repay Maturano for the manly and humane stand he took in this terrible crisis of our fate. The upshot of the whole business was that we resumed our weary march across the plains, avoiding the high ground as much as possible. It rained heavily, and as darkness set in the storm increased in fury. At last our captors, as well as ourselves, began to show signs of exhaustion, and looked around for the most inviting place they could find to camp for the night. I was impressed with the fact that the numbers of the Chileans had decreased measurably since the dramatic council held in the afternoon, and I judged that less than half the force with which they started was now present. The camp was selected in the most sheltered place our captors could find, and a great fire was started, before which we stretched ourselves. The storm moderated during the night, and towards morning the guards who had been set over us yielded to the demands of over-taxed nature and fell asleep at their posts. Not so with our men, however; we were watchful and wary. By each other's help we had so loosened our cords that we could rid ourselves of them at any moment. Instinctively we felt that the time had come when we might recover our liberty, and the whispered word was passed along to stand ready for the attempt. Gun after gun was quietly moved from the sleeping guards and their comrades, until every prisoner had one within easy reach, and at a given signal we rushed to where the leaders were bivouacked and covered them with our weapons. It was the work of a moment to secure their arms, and they were taken in detail and bound firmly with cords. The peons gave us no trouble when they saw that their patrones were in our power.

Tirante was the one most dreaded, and we were careful not only to make him secure, but gave him in special charge of two of our most reliable men. It was now nearing day. We only had a general idea of where we were. We knew that in our last march the evening before we had crossed the main Stockton road and gone for miles in the direction of the Stanislaus river. As daylight broadened, the brightness of the eastern sky gave token of the coming of a clear and stormless day. The weather as well as our own condition had changed within a few short hours. To the fury of the elements had succeeded a grateful calm, and from being prisoners in the power of a ruthless enemy, we had become the captors and they the captives. We lost no time in starting with our prisoners in the direction of the Stockton road, which we reached at a point called O'Neill's ranch. As we approached the well-known capacious tent, we saw one of its inmates astir. On discovering us he hurried over the ravine which lay between us, and informed us that a party from Stockton, who had been on the road looking for us nearly all night, were sleeping in the tent. He ran back with the news, and by the time we arrived at the station the rescuing party had come out and formed a line in front of the tent to receive us. They were completely armed, and I reflected upon what would have happened had this party found us during the night. There would have been a conflict, in which many on both sides would undoubtedly have been killed. In the heat and confusion of the encounter it is probable that we would have suffered from both friends and enemies, and it is likely that with the triumph of the Americans their exasperation would have been so aroused that they would have dispatched the entire band of Chileans.

The Stockton Rangers—that was what we called them—greeted us effusively as we turned our prisoners over to them, and the people of the station hastened to prepare for us a much-needed breakfast. In the meantime I was not forgetful of Maturano and the great service he had rendered us the day before. I knew that if he was taken back to the mines it would fare hard with him, and I concluded that I must act at once or the chance would pass away, perhaps forever. I sought him out and told him that as he had been kind to us I intended to aid him to escape. I walked with him past the tent, and when we reached the open plain where the wild oats was dense and tall, I told him to stoop and get away as fast as he could. He kissed my hand and thanked me, and I stood and watched his course by the trail he made in the tall oats until I was satisfied he was out of danger, and returned to my comrades, to whom I told what I had done. They were greatly pleased, and all, without exception, heartily endorsed and commended my thoughtful action. A strong guard of the Rangers was detailed as an escort to our men to return with the prisoners, whilst Dr. Gill and myself were appointed a committee to go to Stockton and lay the facts before the people and the authorities. On arriving in Stockton we found the community intensely excited, and placards were out calling a mass meeting for that evening. The utmost indignation was directed against Judge Reynolds when it was ascertained that he had issued a writ of arrest, and against the Sheriff for placing it in the hands of the Chileans to serve. Anticipating the coming storm, both the Judge and his Sheriff took hurried departure for San Francisco in a small boat. I never heard of them afterwards. But I was informed that Dr. Concha, who was the real author of all the trouble, was killed at a fandango in San Francisco a few nights afterwards.

The mass meeting was attended by nearly everybody in town. A young man, a nephew of Judge Collier, had come down to Stockton on behalf of the people of the Calaveras camps. He was the principal speaker, and delivered a powerful, eloquent and impassioned address. His speech produced the wildest excitement, and it was well that Judge Reynolds and his Sheriff had got beyond reach of the excited and indignant people. That young orator was Samuel A. Booker, who took up his permanent residence in Stockton soon afterwards and served for many successive terms on the District and Superior benches of San Joaquin county. He was distinguished amongst the many able jurists of this state for the soundness of his opinions and the clearness of his exposition of fundamental principles. After filing our affidavits, Dr. Gill and myself started back for the mountains. On arriving home we found that a large delegation of miners from Mokelumne Hill had organized a court to try the Chileans engaged in the recent lawless and murderous acts. Tirante and two others, to whom were traced directly the murder of Endicott and Starr, were sentenced to death; some four or five of the most active participants in the affair were sentenced each to receive from fifty to one hundred lashes on the bare back; and two, whose culpability was held to have been exceptionally flagitious, were condemned to have their ears cut off.

I have dwelt thus at length and in detail upon this tragic episode in the early history of the mines for the reason that when a few years ago the mob in the streets of Valparaiso maltreated and killed sailors belonging to a United States cruiser on shore leave, the spirit of hatred then shown by the Chileans was ascribed to the treatment their countrymen had received in the mines in 1849. Perverted references were made in the public prints to what was termed the Chilean Massacre in California, and a profound ignorance of the whole affair was manifested both by those who wrote about it and by the mob who thought, if they thought at all, they were carrying out a commendable retaliation. Even this venomous spirit rankled in the breasts of the higher orders of Chile, and at one time it looked as if we would in fact have to bring the peppery little republic to its senses by our strong national arm. The prejudice against Californians in Chile had its incipiency in "the Chilean war" in Calaveras, and I doubt if it would have been safe for any of the American participants in that affair to have visited that country for years after its occurrence and to have been identified as having taken part in the trial and punishment of the murderers of Endicott and Starr.

Over forty years after the event, the seeds of hatred planted in the Chilean breast at that remote period culminated in the brutal assault and murder of our sailors in the streets of Valparaiso and in international complications that nearly led to war between the two countries. How much of this was due to the prejudice, garbled and ignorant reports of the Calaveras affair that reached Chile we cannot know; but we do know that if all the facts had been fairly and truthfully disseminated in that country from the beginning they could not have resulted in a national embitterment which survived for more than a generation the event that gave it birth.