For untold ages the Indian around the site of Volcano had gathered acorns and pine-nuts, and captured the deer and other game with which the hills abounded. But there was gold in the hills, gold on the flats, in the gulches, everywhere; gold that opens the roads to influence, power, and happiness. Men rushed to California to get their share of the gold. The grassy plains have been torn up, the rich soil sluiced through the canon, and are but unsightly piles of rock, holes of mud and stagnant water. The hills, robbed of their graceful pines, are furrowed into deep gullies, while the clear, limpid waters of the creek, turned from the channel and carried into the surrounding hills, are laden with mud, sand, and gravel, carrying destruction to the farms in the valley below.

Such was and such is Volcano. It is not intended to find fault with the work done it is probably well; for until the great balance sheet is made out, who shall say that the activity, the commercial life, the enlarging of man's powers by these operations, may not more than compensate the apparent destruction. The Illinois party, Green & Co., went to work on the ground staked off. The surface was a reddish clay, evidently a wash from the hill to the west. About eight feet from the surface they came to the gravel, which was so rich that they could pick out gold with the fingers. They carried the dirt to the creek, some two hundred yards away, in buckets, and washed it in a rocker. They made about a hundred dollars a day to the man, some of which was coarse gold, one piece being worth over nine hundred dollars (over 45 ounces). At a depth of fifteen feet they struck a yellow colored clay, so tough that they could not wash it, and abandoned the claim as worked out. The same place was worked continually for thirty years. Probably a million of dollars in all was taken put of it, or in the immediate vicinity. Some years after it was known as the Cross and Gordon claim. They had a pump, worked by several horses, to keep the water out. It is said that they divided thirty thousand dollars profits at the end of a year. It was afterwards known as the GEORGIA CLAIM

There were sixteen shares in this company, and the stock was rated as high as three thousand dollars per share. It is said that some of the men carried away as high as thirty thousand dollars each. Various devices were used to get rid of the water. One engineer, of questionable ability, induced them to put in a pendulum pump, with which one man could do as much as several by the ordinary method. A gallows fifty feet high was erected, and a pine log hung in it as a pendulum. Two stout men could scarcely keep the thing swinging with no machinery or pump attached to it, and the machine was consigned to the tomb of all attempts to manufacture power out of nothing. A stout fellow was hired, for four dollars, to keep the water down during the night, which he did and had time to spare to dance away his wages at fifty cents a round, at a dance house in the vicinity. He afterwards found his way to the State prison for the theft of a watch, valued at fifty dollars, at a time that stealing fifty dollars was a capital offense. It may be also mentioned that this same fellow belonged to an organization that had agreed to lick any man that would work for less than four dollars a day.

The claim was afterwards kept dry by a steam engine and pump. Once, in a storm, the water got the better of the engine, and rose several feet above all the works, leaving only the smoke-stack above the water. John Goodwin, a waggish fellow, proposed that a man should take some kindling and wood and dive with it down to the furnace, and start a fire. The plan was not adopted.

To return to the

California Gold Rush of '49:

About the first of October two houses were built, one near the Odd

Fellows' Hall, there being a spring in that vicinity, and also a brush and

pole shanty, covered with dirt, not fara way. Besides the Green company,

there were Dr. Kelsey, afterwards President of the First National Bank,

Stockton, also Treasurer of San Joaquin county, who was afterwards found

dead in a boat on the slough; Bunnel, from Ohio; Ballard, of Illinois;

Kelley, from Ohio; Jacob Cook, now living at Pine Grove; -Henry Hester; Jim

Gould, now at Jackson; Philip Kyle, now of San Joaquin county; Mills, P.

Fellinsbee, McDowell, Rod. Stowell, and other names not remembered, making a

population of about fifty.

Most of the mining was in Soldiers' gulch, the dirt being carried to the creek for washing. A number of men made hand-barrows, on which they carried the dirt. Finally a cart was rigged up, and, with a yoke of cattle to draw it, readily rented for eight dollars per day. Cook & Co., got a barrel of syrup, one of whisky, and one of vinegar, from Sacramento, and started the first store. Syrup was worth five dollars per gallon, vinegar the same, and whisky was fifty cents a drink. They also kept a few boarders, at twenty one dollars per week.

The Indians worked in Indian gulch, hence its name. A Missourian jumped an Indian's hole, throwing out his tools. The Indians came around and ordered him out. Upon his refusing to leave, they drew their bows, and prepared to enforce the command. He ran away, going to Soldiers' gulch, where a party was raised to pursue and chastise the Indians. When the party came in sight, the Indians ran, and the whites fired at them, Rod. Stowell, a Texas ranger, killing one. They followed them towards Russell Hill, occasionally getting sight of them and firing, though no more were killed. The following day, one of a party of three or four men, traveling from Jackson to Volcano, stopped to let his horse eat grass at the flat where Armstrong afterwards built a saw-mill. When the others of the party had got out of sight, the Indians fell upon him and killed him; stripping off his clothes, they partially concealed the body by laying it by the side of a log, and burying it with brush. Being missed, search was made, and his body discovered, the Indians having left one foot sticking out. He was buried at the graveyard hill. This murder was supposed to have been in retaliation for the killing of the Indian by Stowell.

On the approach of Winter, Green's party, with others, numbering about twenty in all, built a log cabin containing several compartments, making it compact to avoid attacks of the Indians, who were evincing some signs of hostility, stealing all the stock they could. They got it all except a mule, which was saved by locking a chain, fastened to a log by a staple and ring, around its neck. There was only one house between Volcano and Jackson, and that was on the top of Tanyard hill. Two of the men in the big cabin died of scurvy during the Winter. Captain Updegraff had a cabin near the Consolation or present Union House.

The rains commenced in the latter part of October. Green's party sunk a hole in Clapboard gulch at the beginning of the rainy season, and got two ounces to the pan, but were obliged to abandon the place on account of water. They afterwards mined in the heads of the gulches, and by the first of January had accumulated about seventy-five pounds of dust, worth about sixteen thousand dollars, when they abandoned the camp as worked out. It may be here remarked that that was the saying when the writer came in 1850. It was said in 1848 that the middle of a few little ravines paid a spade wide and no more. In 1853, when the writer came to Volcano, Fred Wallace, one of the lucky miners, said the camp was worked out, and Jacob Cook, now of Pine Grove, says that in '49 they would have abandoned Volcano if their cattle had not been too poor to draw their wagon up the hill.

During the Winter, Rod Stowell, a Texas ranger, killed Sheldon, a Missourian, by stabbing him with a long knife. The statements concerning this transaction are very conflicting. Stowell claimed that on entering the cabin, which was a kind of public house, Sheldon shut and locked the doors, making him (Stowell) a prisoner, and then drew a knife to kill him, and that he acted in pure self-defense. Jim Gould, an eye-witness, states the house was not closed; that Sheldon drew a small knife and jocularly told Stowell he was going to kill him ; that the killing of Sheldon was uncalled for and wanton. It may be observed that the habit of retributive justice was gradually adopted by early miners as a kind of necessity, and had not grown into a practice at this time, or Stowell might have fared hard at the hands of the miners, who were much shocked at the affair.

In the Spring and Summer many additions were made to the population. Mann, afterwards of Jackson, opened a restaurant meals one dollar. The Hanfords opened a store, with W. I. Morgan as manager, which stock was afterwards increased until it was the largest in the county. The Fourth of July was celebrated by the reading of the Declaration by McDowell, who afterwards resided at Jackson. Mann got up the dinner for five dollars a head. A family camped near Grass Valley about this time, and many of the miners walked out, a distance of three or four miles, to catch a glimpse of a woman.

During .the Winter, portions of the Volcano graveyard were found to be rich in gold, and the gulches were worked much deeper. It now began to be suspected, or rather learned, that the deposits of gold were enormously large, and that they extended to great depths. Henry Jones, L. McLaine, Fred Wallace, Dr. M. K. Boucher, Doctor Yeager, Ike West, Thomas, Ellec Hayes, and others, had claims in Soldiers' gulch that were enormously rich. A cart load of dirt would have two hundred and fifty dollars of gold in it. Sometimes a pan of dirt would contain five hundred dollars. Men who never in their lives had a hundred dollars, would make a thousand dollars a day. A company of Texans would make a hundred dollars each in a day, and gamble it away every night, and come to their claim in the morning broke. This was their way of having a good time, and gambling saloons came in for a large share of the profits. Clapboard gulch also paid good wages to the gold miners; though not so rich as Soldiers' gulch, the pay-dirt was easier washed and near the surface. Indian gulch was also found to be rich, especially at the head. The Welch claim had a mound of dirt a few feet across that had more than a hundred thousand dollars in it. Some of the gold was found in a tough clay that defied washing by any ordinary method. Boiling was found to disintegrate the clay, and boilers were erected in many places to steam it so that it would come to pieces. It was observed that when left in the sun to dry hard, the clay would fall to pieces, and drying yards were established where the rich gold bearing dirt was dried and pounded.

A SHARP MINING BROKER.

A sharp trade was driven in claims, a thousand dollars being frequently

paid for a piece of ground thirty feet square. Moore Lerty was particularly

successful in selling claims. His operations were bold, and perhaps

original. He would open a claim within the vicinity of other productive gold

claims, digging it down to good-looking dirt, and then would load an old

musket with gold-dust, and shoot the ground full of gold. It is said that he

has been known to punish a claim with two or three hundred dollars worth of

gold in this way. If he did not sell the claim, he could wash the dirt, and

recover the dust. He sold a claim for one thousand dollars in this way to

Henry Jones, notably the sharpest man in Volcano. Jones tried the claim for

a day or two before purchasing, it is said, even going into the hole at

night to get the dirt, so as to be sure that he was not imposed on. He found

that all of the dirt was rich in nuggets, so he bought it. The fun of the

matter was in the fact that the place proved to be really rich, one of the

best locations in the camp.

Another salted claim, in China gulch, also proved good, but several of his swindles coming to light, he fled the California gold country before the wrath that began to manifest itself, and left the country. A number of houses of respectable appearance were built in 1851, among which were the Volcano Hotel, by G. W. (renamed the National, by Dr. Flint, of Flint, Bixby & Co.); the Philadelphia House, by Downs, and some others. The last two were standing until a few years since, a relic of pioneer days.

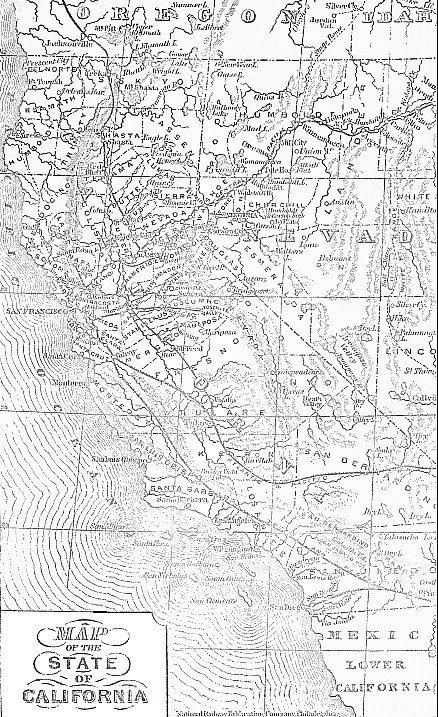

Early Day Map of California