A large part of the world's gold has come from placers, which still yield a significant percentage of the world’s annual production. Placer deposits as a rule are the most easily discovered of all metalliferous deposits, and because their product is so easily transported and marketed the placers are commonly the first resources of a region to be exploited. The lure of gold has resulted wild rushes of exploration and development of many a new country. After many centuries of exploration for gold, it is abundantly clear that there is a relation between gold deposits still in place in the hard rock formation where they were originally formed, and the placer deposits that result from their erosion.

The gold-quartz of the outcrops of quartz-veins is freed from the parent body by erosion and passes either at once into a stream-bed or reaches the latter after a slow journey down the hill-slopes, where its progress towards the valley bottom is dependent on the supply of running water and on the "creep" of the hillside. Where the slopes are flat a certain amount of gold concentration may take place in the soil of the hillside below the vein outcrop by the readier removal of associated quartz. These eluvial deposits are generally not of great economic value, but have been noted in a number of countries. Akin to them are the shallow Aeolian surface deposits of dry desert countries where wind-action has removed the lighter grains of quartz and clay. Both these types are in themselves of limited economic importance on a global scale, but are invaluable as indicating the near proximity of the parent vein.

That placer gold is directly derived by mechanical processes from vein deposits or analogous occurrences is absolutely certain, and examples of convincing character are present everywhere. This does not imply that the primary deposit can always be worked at a profit. In most cases the gold is traceable up to the deposit. On this principle the pocket hunter proceeds, panning the detritus and working up hill until the source of the scattered gold has been found. The area in which the detritus occurs has the shape of a triangle, the apex of which is the gold pocket that is the source of the metal. As a land surface is worn away in regions where conditions are unfavorable for solution, gold contained in veins and veinlets or disseminated in the rock tends gradually to become concentrated at the surface. Some of it may remain practically in place. The rotten outcrops (saprolites) of many veins in the southern Appalachians and the seam diggings of California were washed for gold as placer deposits. As erosion goes on the gold-bearing mantle rock of a deposit on a slope will gradually settle downhill, constituting an eluvial deposit. As erosion is continued further, however, the gold ultimately finds lodgment in streams together with sand and gravel. Such accumulations constitute the principal placer deposits.

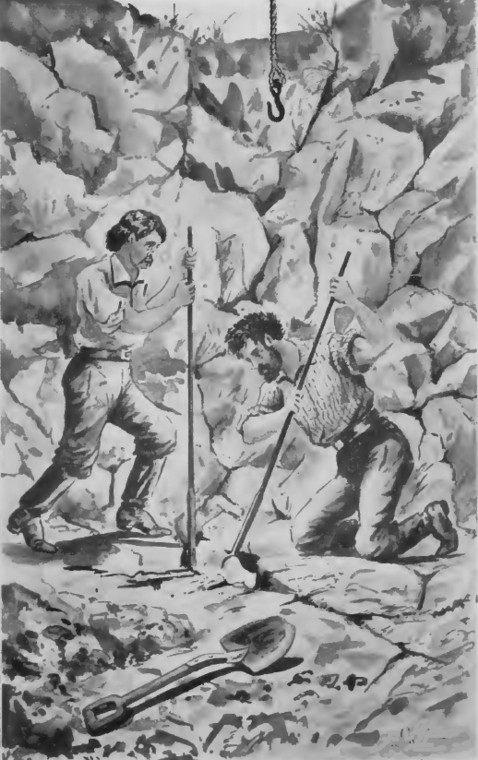

Where gold lodes are exposed it is reasonable to expect placers, and where placers have been found the search for the source of their gold suggests interesting possibilities for prospecting. An experienced prospector will pan the gravels of gulches that drain a region which contains gold deposits and will seek gold lodes in a region which contains gold-bearing gravels. Either the placers or the lodes may be found first; placer gold is easily discovered. It is common practice to follow up a stream, panning it at intervals and to scrutinize the surrounding country carefully where "colors" suddenly cease to appear. This method has proved effective also in prospecting hill slopes for gold lodes, especially in regions that have not been glaciated. The mantle rock is panned at intervals, and a line may be found below which it contains gold and above which gold is absent. Trenching across such a line may disclose a gold bearing lode.

It is a common observation that rivers or creeks crossing a vein or a mineral belt are enriched immediately below it, the coarseness of the gold increasing upstream to the place where the outcrops are crossed. As examples may serve the great accumulations of placer gold in the Neocene gravels of Eldorado County, California, where the Mother Lode crosses them, and the rich channels in upper Nevada County, just below the belt of quartz veins at Washington and Graniteville. There are also fine examples in Victoria, Australia where the gravels are rich only where they cross or follow systems of veins or "reef lines." The White channel of the Forest Hill divide, California, follows a belt of quartz stringers in clay slate. The Idaho Basin presents an excellent instance of large gravel bodies the gold content of which is traceable up to certain auriferous vein systems.

Not all gold lode deposits, however, have associated placers. In some regions gold is dissolved and carried downward in solution, enriching the deposit below. Even where gold is not dissolved it is not invariably concentrated in gravels. It may be so finely divided that it is carried away in the drainage. In panning some deposits a film of gold may be seen floating on top of the water in the pan. Gold as fine as that could easily be carried away by streams and scattered. Placers are not developed from some gold deposits, because the primary ore shoot did not reach the surface and no auriferous rock has yet been eroded. Glacial erosion may remove all mantle rock and stream gravels from lodes in mountainous countries. In some regions fine flaky gold may have been blown away by winds. Examples include the bonanza outcrops of the Coromandel and Thames goldfields, in a country where conditions are peculiarly favorable to surface enrichment, yielded insignificant quantities of alluvial gold. On the eastern or Tokatea slopes of the mountain range at Coromandel, on which the rich Royal Oak and other veins outcropped, not a single color could be obtained by panning, nor were nuggets found in the streams below. The famous Martha system of the Waihi mine, that has yielded nearly seven millions sterling from the uppermost 900 feet alone, gave no alluvial gold, although physical conditions were exceedingly favorable for concentration.

Conversely, in some regions that contain placer deposits no workable gold lodes have been discovered. Where gold is not dissolved from its deposits weathering and erosion are generally very efficient processes in the mechanical concentration of gold. Hundreds or even thousands of feet of material may be eroded from a region, the rock being carried away in streams, whereas the heavier gold remains behind to enrich gravels near the deposits. In many well known “placer only” regions the gold in the gravels has been concentrated from many veins and veinlets that are too small, discontinuous and low in grade to be worked commercially underground. Many quests for the "mother lodes" that were the source of the gold in regions containing valuable and well known placers have proved disappointing. The zones in which these tiny veins exist are sometimes called “stringer zones”. They have been worked as eluvial deposits in some districts, being known as “seam diggings” in California and as “saprolite diggings” in the Appalachian goldfields of the southeastern US. Examples of these types of areas include the Clutha River in New Zealand is derived from small and unimportant quartz veins and veinlets in the quartz-schists of Central Otago. In the Klondike region, despite the extraordinary richness of the gravels, the parent gold-quartz veins of the local schists are apparently worthless. Many similar instances may be cited; and in the majority of these the richness of the gravels cannot be explained by the assumption that the placers owe their value to the degradation of bonanza outcrops, for the formation of the placers has taken place in comparatively recent times, during which climatic conditions have not varied appreciably from those at present prevailing, and these, as in Alaska, British Columbia, and Siberia, are often inimical to outcrop enrichments. Tyrrell has calculated that the gold of the Klondike gravels may be considered to be derived from 900 feet of eroded country, or a total quantity of 1.6 billion (English) tons of rock. Assuming the gravels to contain 10,000,000 ounces of gold, the average gold content of the schist removed has been only .003 grain gold.

Some very old time publications refer to volcanic sources of placer gold, where molten gold was emitted from an active volcano along with the more normal lava flows. This “theory” of placer origins comes from the molten, blob like appearance of many water worn nuggets. It is long been discredited among geologists who have demonstrated that gold simply does not form in this way.

Many prospectors also wonder if secondary processes from near surface water solutions form gold nuggets. It is true that where acid waters containing sodium chloride attack gold in the presence of an oxidizing agent, such as manganese oxide, gold will be dissolved. But waters of streams normally contain very little sodium chloride, and by the processes of sedimentation the light powdery manganese oxides are generally separated from the heavier particles of gold. Moreover, acid waters are neutralized by nearly all minerals, and neutral waters do not dissolve gold. Organic matter also is generally present near the surface and in streams, and it would cause any dissolved gold to be precipitated and inhibit its solution. Thus the normal conditions are adverse to the extensive migration of gold in placer deposits by solution and re-deposition,

although under exceptional conditions such migration probably takes place to a minor extent, however when it does, the secondary gold formed by these processes is nearly always very small in size. Recent scientific testing has shown that nearly all nuggets of any significant size are originally formed by primary geothermal processes deep within the earth.

Ground waters attack other metals more readily than gold. Silver, lead, and copper are dissolved from minerals in which they are associated with gold. Thus the gold in placer deposits will generally be purer than the gold of the lodes from which it is derived, and normally the farther it is from its source, and the finer its particle size, the purer it will be.

Scientists have proved using larger nuggets from the Klondike and elsewhere that the outside actually has a greater fineness than the inside. The loss of silver and copper from the outer surface of the nugget was from 5 to 7 per cent. This interesting result well illustrates the relative insolubility of gold. In Australia the placers have afforded nuggets up to 233 pounds in weight, but, in view of the fact that masses weighing 140 pounds have been found in quartz reefs, it does not seem necessary to claim for the placer nuggets any other than a detrital origin.

Return To:

All About Placer Gold

Deposits