From the time when it first became known to Europeans, Arizona has been especially noted for its mineral wealth. There is no evidence that its mines were ever worked by the aborigines; but by the Spaniards its treasure of precious metals was much talked of, even before being found. It was enough to know that the country was in the mysterious north, and occupied by savage tribes ; its wealth was taken for granted. On its partial exploration, however, and the establishment of missions and presidios on its borders early in the eighteenth century, abundant indications of native gold and silver ore were found in all directions. Yet so broad and rich was the mineral field farther south, and so feeble the Spanish tenure in Alta Pimeria by reason of Indian hostility, that not even the wonderfully rich 'planchas de plata' at the Arizona camp, giving name to the later territory though not within its limits, led to the occupation of the northern parts by miners. As I have already explained, the current traditions of extensive mining in Spanish times are greatly exaggerated. The Jesuits worked no mines; and in their period, down to 1767, nothing was practically accomplished beyond irregular prospecting in connection with military expeditions and the occasional working of a few veins or placers for brief periods, near the presidios. It is doubtful that any traces of such workings have been visible in modern times. Later, however, in about 1790-1815, while the Apaches were comparatively at peace and all industries flourished accordingly, mines were worked on a small scale in several parts of what is now Pima County, and the old shafts and tunnels of this period have sometimes been found, though the extent of such operations has been generally exaggerated. With Mexican independence and a renewal of Apache raids, the mining industry was entirely suspended, only to be resumed in the last years, if at all, on a scale even smaller than before 1790.

Still the fame of hidden wealth remained and multiplied; and on the consummation of the Gadsden purchase in 1854, as we have seen, Americans like Poston and Mowry began to open the mines. Eastern capital was enlisted; several companies were formed; mills and furnaces were put in operation; and for some six years, in the face of great obstacles ónotably that of expensive transportation. The southern silver mines were worked with considerable success and brilliant prospects, until interrupted by the war of the rebellion, the withdrawal of troops, and the triumph of the Apaches in 1861. The mining properties were then plundered and destroyed, many miners were killed, and work was entirely suspended, not to be profitably resumed in this region for many years.

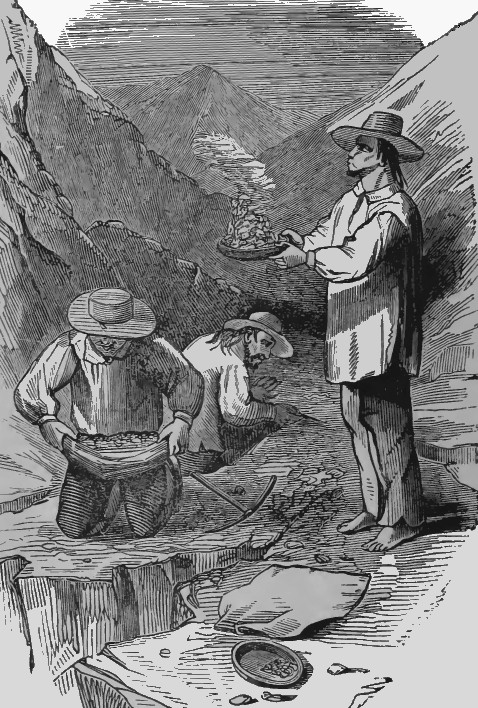

During this period the Ajo copper mines in Papaguena were also worked with some success, both mines producing rich copper ore; and on the lower Gila from 1858 gold placers, or dry washings, attracted a thousand miners or more, being somewhat profitably worked for four years, and never entirely abandoned. In 1862 the placer gold rush excitement was transferred northward across the Gila, and up the Colorado to the region where La Paz, Olive City, and. Ehrenberg soon came into existence. For several years these Colorado placers attracted a crowd of Californians, and a large amount of coarse gold nuggets were obtained; but as a rule the dry washing processes were too tedious for the permanent occupation of any but Mexicans and Indians; and the Americans pushed their prospecting north-eastward, under the pioneers Pauline Weaver and Joseph Walker, for whom new and rich districts in what is now Yavapai county were named in 1863.

Not only was the placer field thus extended, but rich gold and silver bearing veins were found, giving promise of a permanent mining industry for the future. Such was the state of affairs in 1864-5, when the territory of Arizona was organized; and the mining excitement in Yavapai doubtless had much influence in making Prescott the capital. This excitement continued for years, new and rich discoveries being frequent; but the richest lodes were always those to be discovered a little farther on in the Apache country.

The Apache war soon made mining and even prospecting extremely perilous in most regions, at the same time preventing the influx of capital from abroad; and in many of the mines that could be worked it was soon found that the ores were too refractory for reduction by the crude processes and with the imperfect machinery of the pioneers. One or two mines of extraordinary richness were continuously profitable; a few others paid well at times; many men gained a living by working placers and small veins; and some mines near the Colorado made a profit by sending selected ores at enormous cost to San Francisco. Meanwhile every military expedition was also a prospecting tour; and the attitude of the people was one of most impatient waiting for the time when, with the defeat of the Apache and the return of peace, the development of mineral wealth might begin in earnest. Enthusiasm over the country's prospects was unbounded; the local newspapers were full of rose-colored predictions; the governor and legislature were strong in the faith ; and the government commissioners of mining statistics, Ross Browne and R. W. Raymond, gave some prominence to Arizona in their reports.

With the end of Apache war in 1874 came the expected revival and development of mining industry, old mines being worked with profit, and many new lodes being brought to light, notably in the central region of Gila and Pinal counties. The revival extended to the old districts of Pima county in the south, where the mines had been practically abandoned for thirteen years. While, however, there was marked progress in discoveries and workings, and in the influx of population, the output of bullion beginning also to assume proportions, yet the grand 'boom' was hardly so immediate or complete as Arizonans, in their long pent enthusiasm, had hoped for. Capital was still somewhat timid and tardy in its approach; the Indians became again to a certain extent troublesome; and above all, the cost of transportation was enormous.

The railroad then became the prospective panacea for all the territory's ills. It reached the Colorado border in 1878, and five years later two lines extended completely across the country from east to west. The railroad, with its policy of demanding "all the traffic will bear," by no means put an end to excessively high rates, yet it afforded some relief; and meanwhile the discovery of the Tombstone bonanzas, aided by the failure of the Comstock lode as a paying property, gave to Arizona in 1880-4 a very high and previously unexcelled degree of prosperity. In 1884-6, however, the extremely low price of silver and copper bullion, together with labor troubles and a disastrous fire in the south-east, and the bursting of the Quijotoa bubble, have thrown over the country's progress a cloud, which it is hoped will soon disappear.

The total native gold and silver product of the Arizona mines has been perhaps about $60,000,000. For the decade ending in 1869 it was estimated, on no very secure basis, at $1,000,000 per year on an average. Then it fell off to $800,000, to $600,000, and in 1873-4 to $500,000, being $750,000 in 1875. For the next four years it averaged about $2,000,000. For 1880 the amount is given as $5,560,000; for 1881 it was $8,360,000; and for 1882 over $8,500,000. In 1883-4 the production fell off to about $6,000,000, and to a still less figure probably in 1886. Down to the end of the Apache war the amount of gold largely exceeded that of silver, but later was only about one sixth, though exceeding $1,000,000 in 1881-2.

Return

to The Arizona Page:

Arizona Gold Rush Mining History