Wonderful stories were told of the amount of gold and silver to be seen in the seven cities of Cibola, and expeditions were sent by the Viceroy of Mexico to find and seize the coveted treasure. A number of expeditions were sent out, but nothing was accomplished by these expeditions but the partial destruction of a peaceful, native race, who had made considerable progress in civilization. Afterwards, that order, whose piety and zeal have furnished throughout the New World, so many pioneers, the Jesuits began founding missions in this unknown land. Through one of these missions, located near the Santa Rita Mountains, the discovery of rich silver mines was made. A Yaqui Indian is said to have made the discovery in 1769. On, and immediately below the surface of the ground, pure silver in large pieces were found, many of which weighed twenty-five and fifty lbs., several 500 lbs., and one mass is particularly spoken of, which gave 3,500 lbs. after being fused, and divided on the spot where it was discovered in order to remove it. This caused a considerable stir among the population and a large population was immediately attracted to these mountains by this discovery, and the valley of the Santa Cruz became the center of active mining operations.

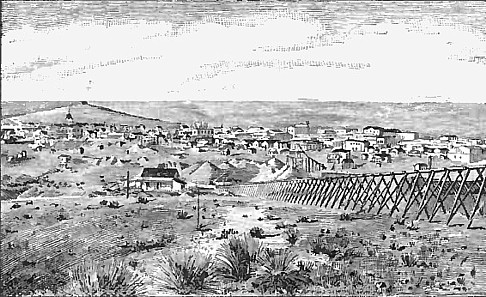

The town of Tubac was probably the largest mining village. Within a circuit of fifteen miles around this town, one hundred and fifty silver mines were more or less worked. Other rich districts were found in this range of mountains, and worked at great profit, large quantities of silver being taken out and carried into the towns of Sonora. Seven years after the first discovery, the king of Spain, who had seized considerable of the treasure first taken out, decided that all the native silver pertained to the private patrimony of the crown, and that the mines in future should be worked for his special profit. This decree did much to discourage mining, although considerable was carried on more or less secretly by the Jesuits, but often entirely interrupted by the hostility of the Indians. When the revolution in Mexico occurred, these missionaries were banished, and their property confiscated, then mining entirely ceased, and now, even the exact location of such mines as the Tumacacori, Salero, and Plancha de la Plata, the richness of which is a matter of record, is unknown.

Recent prospectors claim to have rediscovered them; whether or not they have done so, it is certain that their search has been rewarded by new discoveries, which, in importance, may exceed those of old. In 1857, this Territory having been purchased by the United States, the Americans turned their attention to this rich silver district, and commenced work on several mines. During the next four years, many new mines were located. The rebellion caused a total cessation of work, and very little attention was paid to the mines in this section till 1875, when the discovery of wonderfully rich districts in the Pinal and Apache ranges of mountains, north of the Gila River, gave a new impetus to mining throughout the Territory. These discoveries were followed in 1877 by what appears to be a still more important one in the southeastern part of our Territory, that of the Tombstone mines, which have already given evidence of being among the richest in the world.

The developments already made leave no doubt as to the permanency of the mines of Arizona. Innumerable ledges have been found containing rich ore near the surface, but in many cases as depth is attained the ores grow richer. The veins dive into the earth at all angles of inclination, giving us vertical lodes and blanket lodes, as they do in other countries. They pinch into narrow seams, give out, come in again, swell into large masses, the same as mineral veins all over the world. Every known variety of silver ore is found divided into the two classes, in reference to reduction, of milling ore and smelting ore, and these two classes are found in the same kind of formation with the same general differences as are recognized in other sections. The word fissure in its application to mineral veins is founded on a theory in regard to their formation by no means generally accepted, and we think the tendency is to reject the theory and retain the word only as descriptive of a large and permanent vein. Still using it in its old sense, all the important mines here give, so far as they have been developed, the same evidence of being true fissure veins as the mines of Nevada and Mexico. No known case of giving out has yet occurred, though several mines which have paid from the surface have reached a depth of 600 feet.

The large amount of float ore found here might be cited as an evidence of the permanence of the veins, indicating not only the length of time which nature has been tearing them down, but also the great period during which circumstances were favorable for their formation. Those who believe that mineral veins are the result of infiltration or segregation from, or near the surface, will be likely to consider the depth to which such veins might reach in a country which has been drained to so great a depth. Wherever a number of veins giving good promise have been found within a neighborhood of a few miles, the section has been formed into a mining district. These districts are of all sizes, containing from 25 to 2,000 square miles. Over eighty have been formed, and additions are constantly being made. They contain from 100 to 3,000 locations each. Every location indicates the appearance of ore in greater or less quantities, and we may thus obtain an idea of the vast extent of country which is permeated by mineral veins in this Territory.

Return

to The Arizona Page:

Arizona Gold Rush Mining History