The miners were a nomadic race, with prospectors for advance guard. Prospecting, the search for new gold-fields, was partly compulsory, for the over-crowded gold camp or district obliged the new-comer to pass onward, or a claim worked out left no alternative. But in early days the incentive lay greatly in the cravings of a feverish imagination, excited by fanciful camp-fire tales of huge ledges and glittering nuggets, the sources of these bare sprinkling of precious metals which cost so much toil to collect. Distance assists to conjure up mirages of ever-increasing enchantment, encircled by the romance of adventure, until growing unrest makes hitherto well-yielding and valued claims seem unworthy of attention, and drives the holder forth to rove. He bakes bread for the requirements of several days, takes a little salt, and the cheering flask, and with cup and pan, pick and shovel, attached to the blanket strapped to his back, he sallies forth, a trusty rifle in hand for defense and for providing meat. If well off he transfers the increased burden to a pack animal; but as often he may be obliged to eke it out with effects borrowed from a confiding friend or storekeeper. Following a line parallel to the range, northward or south, across ridges and ravines, through dark gorges, or up some rushing stream, at one time he is seized with a consciousness of slumbering nuggets beneath his feet, at another he is impeded onward to seek the parent mass; but prudence prevails upon him not to neglect the indications of experience, the hypothetical watercourses and their confluences in dry tracts, the undisturbed bars of the living streams, where its eddies have thrown up sand and gravely the softly rounded gravel-bearing hill, the crevices of exposed rocks, or the out-cropping quartz veins along the bank and hillside. Often the revelation comes by accident, which upsets sober-minded calculation; for where a child may stumble upon pounds of metal, human nature can hardly be content to toil for a pitiful ounce.

Rumors of success are quickly started, despite all care by the finder to keep a discovery secret, at least for a time. The compulsion to replenish the larder is sufficient to point the trail, and the fox-hound's scent for its prey is not keener than that of the miner for gold. One report starts another; and some morning an encampment is roused by files of men hurrying away across the ridge to new-found treasures. Then spring up a camp of leafy arbors, brush huts, and peaked tents, in bold relief upon the naked bar, dotting the hillside in picturesque confusion, or nestling beneath the foliage. The sounds of crowbar and pick echo from the cliffs, and roll off upon the breeze mingled with the hum of voices from bronzed and hairy men, who delve into the banks and hill-slope, coyote into the mountain side, burrow in the gloom of tunnels and shafts, and breast the river currents. Soon drill and blast increase the din; flumes and ditches creep along the canon walls to turn great wheels and creaking pumps. Over the ridges come the mule trains, winding to the jingle of the leader's bell and the shouts of the teamsters, with fresh wanderers in the wake, bringing supplies and consumers for the stores, drinking-saloons, and hotels that form the solitary main street. Here is the valve for the pent-up spirit of the toilers, lured nightly by the illumined canvas walls, and the boisterous mirth of revelers, noisy, oath breathing, and shaggy ; the richer the more dissolute, yet as a rule good-natured and law-abiding. The chief cause for trouble lay in the cup, for the general display of arms served to awe criminals by the intimation of summary punishment ; yet theft found a certain encouragement in the ease of escape among the ever moving crowds, with little prospect of pursuit by preoccupied miners.

The great gatherings in the main street occurred on Sundays, when after a restful morning, though unbroken by the peal of church bells, the miners gathered from hills and ravines for miles around for marketing and relaxation. It was the harvest day for the gamblers, who raked in regularly the weekly earnings of the improvident, and then sent them to the store for credit to work out another gambling stake. Drinking saloons were crowded all day, drawing pinch after pinch of gold-dust from the buck-skin bags of the miners, who felt lonely if they could not share their gains with bar-keepers as well as friends. And enough there were of these to drain their purses and sustain their rags. Besides the gambler, whose abundance of means, leisure, and self-possession gave him an influence second in this respect only to that of the store-keeper, the general referee, adviser, and provider, there was the bully, who generally boasted of his prowess as a scalp-hunter and duelist with fist or pistol, and whose following of reckless loafers acquired for him an unenviable power in the less reputable camps, which at times extended to terrorism.

His opposite was the effeminate dandy, whose regard for dress seldom reconciled him to the rough shirt, sash-bound, tucked pantaloons, awry boots, and slouchy bespattered hat of the honest, unshaved miner, and whose gingerly handling of implements bespoke in equal consideration for his hands and back. Midway stood the somewhat turbulent Irishman, ever atoning for his weakness by an infectious humor; the rotund Dutchman ready to join in the laugh raised at his own expense ; the rollicking sailor, widely esteemed as a favorite of fortune. This reputation was allowed also to the Hispano Californians, and tended here to create the prejudice which fostered their clannishness. Around flitted Indians, some half-naked, others in gaudy and ill-assorted covering, cast-offs, and fit subjects for the priests and deacons, who, after preaching long and fervently against the root of evil, had come to the hills to tear it out of the ground by hand. On week days dullness settled upon the camp, and life was distributed among clusters of tents and huts, some of them sanctified by the presence of a woman as indicated by the garden patch with flowers For winter, log and clapboard houses replaced to a great extent the precarious tent and brush hut, although frequently left with sodded floor, bark roof, and a split log for the door. The interior was scantily provided with a fixed frame of sticks supporting a stretched canvas bed, or bolster of leaves and straw. A similarly rooted table was at times supplemented by an old chest, with a bench or blocks of wood for seats. A shelf with some dingy books and papers, a broken mirror and newspaper illustrations adorned the walls, and at one end gaped a rude hearth of stones and mud, with its indispensable frying-pan and pot, and in the corner a flour-bag, a keg or two, and some cans with preserved food. The disorder indicated a batchelor's quarters, the trusty rifle and the indispensable flask and tobacco at times playing hide and seek in the scattered rubbish.

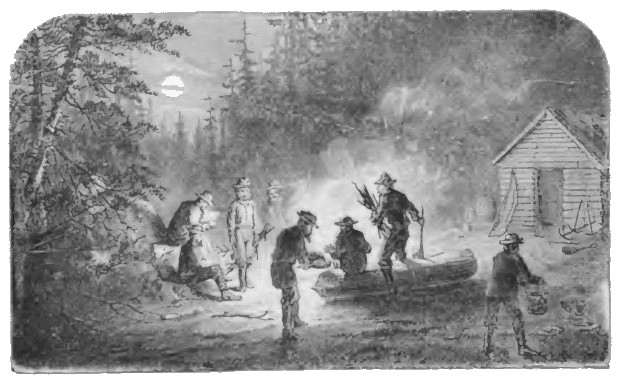

The inmates were early astir, and the cabin stood deserted throughout the day, save when some friend or wanderer might enter its unlocked precincts, welcome to its comforts, or when the owners could afford to return for a siesta during the midday heat. Toward sunset the miners came filing back along the ravines, gathering sticks for the kitchen fire, and merrily speeding their halloos along the cliffs, whatsoever may have been the fortune of the day. If several belonged to the mess, each took his turn as cook, and preceded the rest to prepare the simple food of salt pork and beans, perhaps a chop or steak, tea or coffee, and the bread or flapjack, the former baked with saleratus, the latter consisting of mere flour and water and a pinch of salt, mixed in the gold-pan and fried with some grease.

Many a solitary miner devoted Sunday to prepare supplies of bread and coffee for the week. Exhausted nature joined with custom in sustaining a change of routine for this day, and here it became one for renovation, bodily and mental, foremost in mending and washing, brushing up the cabin, and preparing for the coming week's campaign, then for recreation at the village. Every evening also, the camp fire, replenished by the cook, drew convivial souls to feast on startling tales or yarns of treasure troves, on merry songs with pan and kettle accompaniment, on the varying fortunes of the cards. A few found greater interest in a book, and others, lulled by the hum around, sank into reverie of home and boyhood scenes. The young and unmated could not fail to find allurement in this free and bracing life, with its nature environment, devoid of conventionalisms and fettering artificiality, with its appeal to the roving instinct and love of adventure, and its fascinating vistas of enrichment. Little mattered to them occasional privations and exposure, which were generally self-imposed and soon forgotten midst the excitement of gold-hunting.

Even sickness passed out of mind like a fleeting night mare. And so they kept on in pursuit of the will-o'-the-wisp of their fancy, neglecting moderate prospects from which prudent men were constantly getting a competency. At times alighting upon a little "gold pile" which too small for the rising expectation was lavishly squandered, at times descending to wage-working for relief. Thus they drifted along in semi-beggary, from snow-clad ranges to burning plain, brave and hardy, gay and careless, till lonely age crept up to confine them to some ruined hamlet, emblematic of their shattered hopes—to find an unnoticed grave in the auriferous soil which they had loved too well. Shrewder men with better directed energy took what fortune gave, or combining with others for vast enterprises, in tunnels and ditches, hydraulic and quartz mining, then turning, with declining prospects, to different pursuits to aid in unfolding latent resources, introducing new industries, and adding their quota to progress, throwing aside with a roaming life the loose habits of dress and manner. This was the American adaptability and self-reliance which, though preferring independence of action, could organize and fraternize with true spirit, could build up the greatest of mining commonwealths, give laws to distant states, import fresh impulse to the world's commerce, and foster the development of resources and industries throughout the Pacific.

The broader effect of prospecting, in opening new fields, was attended by the peculiar excitement known as rushes, for which Californians evinced a remarkable tendency, possessed as they were by an excitable temperament and love of change, with a propensity for speculation. This spirit, indeed, had guided them on the journey to the distant shores of the Pacific, and perhaps one step farther might bring them to the glittering goal The discoveries and troves made daily around them were so interesting as to render any tale of gold credible. An effervescing society, whose day's work was but a wager against the hidden treasure of nature, was readily excited by every breeze of rumor. Even men with valuable claims, yielding perhaps $20 or $40 a day, would be seized by the vision and follow it, in hopes of still greater returns. Others had exhausted their working-ground, or lay under enforced inactivity for lack or excess of water, according to the nature of the field, and were consequently prepared to join the current of less fortunate adventurers. So that the phenomenon of men rushing hither and thither for gold was constant enough within the districts to keep the population ever ready to assist in extending the field beyond them. The Mariposa region received an influx in 1849, which two years later flitted into Kern, yet left no impression to guard against the great Kern River excitement of 1855, when the state was disturbed by the movement of nearly 5,000 disappointed fortune-hunters.

An examination of the encircling ranges led to more or less successful descents upon Walker River and other diggings, which served to build up the counties of Mono, Inyo, and San Bernardino, while several smaller detachments of miners at different periods startled the staid old coast counties, from Los Angeles to Monterey and Sonoma, with delusive statements based on faint auriferous traces. Eastward the fickle enchantress led her train on a wild-goose chase to Truckee Lake,' in 1849, and in the following year she raised a mirage in the form of a silver mountain, while opening the gate at Carson Valley to Nevada's silver land, which was occupied by the multitude in 1860 and the following years (Truckee Lake is now known as Donner Lake). The same eventful 1850 saw considerable northern extensions arising from the Gold Lake fiction, which drew a vast crowd toward the headwaters of Feather River. Although the gold lined lake presented itself, a fair compensation was offered at the rich bars of the stream. Another widely current story placed the once fabulously rich mine of 1850, known as the Lost Cabin, in the region of the upper Sacramento or McLeod River, and kept hundreds on a mad chase for years. North-eastward on the overland route a party of emigrants of 1850 invested in Black Rock City with a silver-spouting volcano, although long searches failed to reveal anything better than obsidian. More stupendous was the Gold Bluff excitement of 1850-1, an issue of the chimerical expedition to Trinidad Bay, the originators of which blazoned before San Francisco that millions' worth of gold lay ready-washed upon the ocean beach, disintegrated by waves from the speckled bluffs. The difficulty was to wrest from the sand the little gold actually discovered. Some of the deluded parties joined in the recent Trinity River movement, and participated in the upper Klamath rush, which in its turn led to developments on Umpqua and Rogue rivers.

In this way the extreme borders of California were early made known, and restless dreamers began to look beyond for the sources to which mystery and distance lent additional charm, enhanced by increasing dangers. Large numbers sought Lower California and Sonora at different times, particularly Frenchmen and Mexicans embittered by the persecution of the Anglo-Saxons. A similar feeling prompted many among those who in 1852-3 hastened to the newly found gold-fields of Australia. In 1854 nearly 2,000 men were deluded by extravagant accounts of gold in Panama, journals to flock toward the headwaters of the Amazon, on the borders of Peru. In the opposite direction British Columbia became a goal for wash-bowl pilgrims, who, often vainly scouring the slopes of Queen Charlotte Island in 1852, found in 1858, upon the Fraser River, a shrine which drained California of nearly twenty thousand sturdy arms, and for a time cast a spell upon the prospects of the Golden Gate. From hence the current turned, notably between 1861-4, along the River of the West into wood-clad Washington, over the prairie regions of Idaho, into silver-tinted Nevada, and to the lofty tablelands of Colorado.

Although California has become more settled and sedate, with industrial and family ties to link them to one spot, yet a proportion of restless, credulous beings remain to drift with the next current that may come. They may prove of service, however, in warning or guiding others by their experience. Excitements with attendant rushes have their value, even when marked by suffering and disappointment. They are factors of progress, by opening dark and distant regions to knowledge and to settlement; by forming additional markets for industries and stimulated trade; by unfolding hidden resources in the new region wherewith to benefit the world, while establishing more communities and building new states. Each little rush, like the following of a wild theory or a dive into the unknowable, adds its quota to knowledge and advancement, be it only by blazing a fresh path in the wilderness. Local trade and conditions may suffer more or less derangement, and many a camp or town be blotted out, but the final result is an ever-widening benefit.The sudden development of mining in California, by men new to the craft, allowed little opportunity for introducing the time-honored recreations which have grown around the industry since times anterior to cuneiform or Coptic records. Even Spanish laws, which governed the experienced Mexicans, had little influence, owing to the subordinate position held by this race, and to the self-adaptive disposition of the Anglo-Saxons. In the course of time, however, as mining assumed extensive and complicated forms, in hydraulic, quartz, and deep claims, European rules were adopted to some extent, especially German and English, partly modified by United States customs, and still more transformed here in accordance with environment and existing circumstances. In truth, California gave a molding to mining laws decidedly her own, which have acquired wide-spread recognition, notably in gold regions, where their spirit, as in the golden state, permeates the leading institutions.

The California system grew out of necessity and experience, based on the primary principle of free land, to which discovery and appropriation gave title. At first, with a large field and few workers, miners skimmed the surface at pleasure ; but as their number increased the late-coming and less fortunate majority demanded a share, partly on the ground that citizens had equal rights in the national or paternal estate, and superior claims as compared with even earlier foreign arrivals on the spot. And so in meetings, improvised upon the spot, rules were adopted to govern the size and title to claims and the settlement of disputes. On the same occasion a recorder was usually elected to register the claims and to watch over the observance of the resolutions, although frequently officers were chosen only when needed, custom and hearsay serving for guidance.

The size of claims varied according to the richness of the locality, with due regard for its extent, for the number of eager participants composing the meeting, and the difficulty of working the ground; so that in some districts they were limited to ten feet square; in others they covered fifty feet along the river, while in poorer regions one hundred or more feet were allowed; and this applied also to places involving deep digging, tunnels, and other costly labor, and to old fields worked anew. The discoverer generally obtained the first choice or a double lot. Claims were registered by the recorder, usually for a fee of $1, and frequently marked by stakes, ditches, and notices. Possessory rights were secured by use, so that a certain amount of work had to be done upon the claim to hold it, varying according to the depth of the ground, the nature of the digging, whether dry or with water accessible, and the condition of the weather. For a long time holders were, as a rule, restricted to one claim, with no recognition of proxies, but the transfer of claims, like real estate property, soon sprang into vogue, with the attendant speculation. Disputes were settled in certain cases by appeal to a meeting, but generally by the recorder, alcalde, or a standing committee.

Return To The Main Page: California Gold Rush: True Tales of the 49ers