July 4th: Here we are, at length, in the gold diggings. Seated around us, upon the ground, beneath a large oak, are a group of wild Indians, from the tribe called the "Diggers," so named from their living chiefly upon roots. These Indians are of medium size, seldom more than five feet and eight or ten inches high; of a dark complexion, with long black hair which comes down over the face. They weave a basket of willow so closely as to hold water, in which they boil their mush, made of acorns dried and pounded to a powder, or their flour, purchased at some trading tent. They have brought us in some salmon, one of which weighs twenty-nine pounds. These they spear with great dexterity, and exchange for provisions, or clothing, and ornaments of bright colors.

We are surrounded on all sides by high, steep mountains, over which are scattered the evergreen and white oak, and which are inhabited by the wolf and bear. This will always be to us a memorable fourth of July, as being our first day at the California gold mines. We have spent the day in prospecting. This term, as it designates a very important part of the business of mining, requires explanation. I should first, however, give some description of the bar upon which we are to labor. This lies on both sides the river, and is covered with smooth, brassy-looking rocks, some of which weigh many tons. It is a little higher than the water-level ; but we find, as we dig down, that the water soon begins to flow in, and must be "baled out." This bar, or rather a succession of bars, extends a distance of some miles up and down the river, over which the water runs with surprising rapidity in the freshets, which are common during the rainy reason, and break up and reduce the gold-bearing quartz, tearing it away from its primitive bed, robbing it, in its course, of its virgin gold, and breaking it down until it is at length deposited, in greater or less abundance, within some crevice or some water-worn hollow, or beneath some rock so formed as to receive it. These bars vary from a few feet to several hundred yards in width. In order to find the deposits, the ground must be "prospected."

A spot is first selected, in the choice of which science has little and chance every thing to do. The stones and loose upper soil, as also the subsoil, almost down to the primitive rock, are removed. Upon or near this rock most of the gold is found ; and it is the object, in every mining operation, to reach this, however great the labor, and even if it lies forty, eighty, or a hundred feet beneath the surface. If, when this strata-belt of rock is attained, it is found to present a smooth surface, it may as well be abandoned at once; if soft and friable, or if seamed with crevices, running at angles with the river, the prospect of the miner is favorable. Some of the dirt is then put into a pan, and taken to the water, and washed out with great care. The miner stoops down by the stream, choosing a place where there is the least current, and, dipping a quantity of water into the pan with the dirt, stirs it about with his hands, washing and throwing out the large pebbles, till the dirt is thoroughly wet. More water is then taken into the pan, and the whole mass is well stirred and shaken, and the top gravel thrown off with the fingers, while the gold, being heavier, sinks deeper into the pan. It is then shaken about, more water being continually added, and thrown off with a sideway motion, which carries with it the dirt at the top, while the gold settles yet lower down. It must be often stirred with the hands to prevent "baking," as the hardening of the mud at the bottom is called. When the dirt is nearly washed out, great care is requisite to prevent the lighter scales of gold from being washed out with the magnetic sand, which is best done by pushing back the gold, and cleaning the sand from the edge of the pan with the thumb. At length a ridge of gold scales, mixed with a little sand, remains in the pan, from the quantity of which some estimate may be formed of the richness of the place.

If there are five to eight grains, it is considered that "it will pay." If less gold is found, the miner digs deeper or opens a new hole, till he finds a place affording a good prospect. When this is done, he sets his cradle by the side of the stream, in some convenient place, and proceeds to wash all the dirt. This is aptly named prospecting and is the hardest part of a miner's business. Thus have we been employed the whole of this day, digging one hole after another — washing out many test-pans — hoping, at every new attempt, to find that which would reward our toil, and we have made ten cents each.

July 5th. My share to-day is $1.25. These details may appear dull and uninteresting ; but the reader will bear in mind that it is the writer's object to give a full and true description of a miner's life. He might pass by all the days and months of profitless labor, and record only the days of success; but those who have friends at the mines, and those who purpose going there, will certainly wish to know what are the trials and discouragements of such a life. They wish to know the truth.

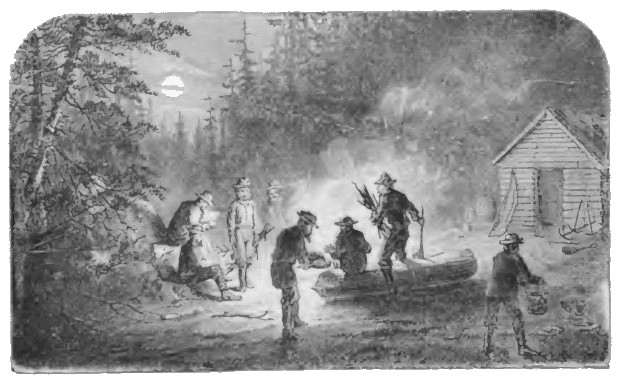

July 6th. We have to-day removed to the opposite side of the river. This, with pitching our tent, has occupied most of the day. Still, we have made $4 each. I have been seated for several hours by the river side, rocking a heavy cradle filled with dirt and stones. The working of a cradle requires from three to five persons, according to the character of the diggings. If there is much of the auriferous dirt, and it is easily obtained, three are sufficient; but if there is little soil, and this found in crevices, so as only to be obtained with the knife, five or more can be employed in keeping the cradle in operation. One of these gives his whole attention to working the cradle, and another takes the dirt to be washed, in pans or buckets, from the hole to the cradle, while one or two others supply the buckets.

The cradle, so called from its general resemblance to that article of furniture, has two rockers, which move easily back and forth in two grooves of a frame, which is laid down firmly on the edge of or over the water, so that the person working it may at the same time dip up the water. It must be inclined a few degrees forward, that the dirt may be washed gradually out, and must be so placed that the mud may be carried off with the stream. Gleets are nailed across the bottom of the body, over which the loose dirt passes with the water, and behind which the magnetic sand and gold settle. An apron is placed beneath the hopper, and conducts the water, dirt, &c., from that to the body below — a construction similar to that of the common fanning-mill. The hopper, which is placed at the top of the cradle behind, is a box, the bottom of which is a sheet of tin, zinc, or sheet iron, perforated with holes from the size of a gold dollar up to that of a quarter eagle.

Through these the dirt, gravel, and gold are all carried by the water upon the apron and into the body below, leaving only the pebbles, too large to be passed through, in the hopper, which are thrown out by raising it in the hands, and by a sudden forward, then backward motion, depositing them on one side in a heap. To facilitate this operation, the hopper is sometimes made with hinges, by which means, by the raising the forward end, the dirt falls over behind. There is generally a handle, so placed on one side that the cradle may be rocked with the left hand, leaving it to the choice of the person rocking: whether to stand or sit while at work. The dirt taken from the hole is turned into the hopper at the top. The person, rocking the cradle with his left hand, at the same time uses his right in dipping up continually ladles of water, which he dashes upon the dirt in the hopper. Twenty-five buckets of dirt are generally washed through, the mass in the body of the cradle being occasionally stirred up to prevent its hardening, and thus causing the gold to slide over it and be lost. It is then drawn off into a pan through holes at the bottom of the cradle, and “panned out," or washed, in the same way as in prospecting.

While this is being done by one of the company, it is common for the others to spend the ten minutes' interval in resting themselves. Seated upon the rocks about their companion, they watch the ridge of gold as it dimples brightly up amid the black sand, seeming to me always the smile of hope, while many enlivening remarks and the cheering laugh go round. At length, the washing completed, the pan passes from one to another, while each one gives his opinion as to the quantity. The holes in the bottom of the cradle are stopped, more dirt is thrown into the hopper, and again the grating, scraping sounds are heard which are peculiar to the rocking of the cradle, and which, years hence, will accompany our dreams of the mines.

Return To The Main Page: California Gold Rush: True Tales of the 49ers