Dec. 3rd. Lying awake in my tent last night, I overheard three miners, "who had come in partially intoxicated at midnight to their tent, within a few feet of us, talking over their plans. It seemed that one of them had just weighed the gold they had made that day, and found it nine ounces. They were to be up early, and start for the same place again. Iconformed my movements to theirs the next forenoon, with an experienced miner for a companion. "With our picks and spades, we soon reached the place where they were at work. They were in the middle of the channel, having turned the stream from its course, up to their knees in the mud and water, while one of their number was constantly employed in "bailing out." We prospected near them for a few hours, as they told us many others had done, unsuccessfully. They did not themselves expect to find employment for more than two days, the deposit already beginning to fail.

Dec. 4th. There was a large fall of snow last night, which pressed so heavily upon our tent that it fell in upon us ; but we kept our beds till morning, the bank of snow above us adding not a little to the warmth of our blankets. I went down, after breakfast, to the diggings, and brushing away the snow, and breaking the ice, attempted to wash out some gold in a pan ; but I made nothing. Becoming thoroughly chilled, with my hands and feet frostbitten, I returned to my tent ; but here it is almost as bad. The canvas, of which our tent is made, is under the snow, our provisions scarce, the fire out, and the day very cold. Two of my companions, feeling the pressure of hunger, went to the tent of an acquaintance, where they found some venison steaks and bread, which had been left at breakfast. They made their dinner from these, being comforted by the thought that some coyote or stray dog would bear the blame. What renders our situation more deplorable is the want of proper clothing. Good boots are so scarce that $96 are readily given for a pair.

A miner related in my hearing to-day the manner in which he employed others to work for him. He marked off a claim ten feet square, and commenced digging in one corner of it. Finding it likely to be a more serious job than he anticipated, and being tired of it, and yet not willing to abandon it without knowing what lay at the bottom, he concealed several pieces of gold, one weighing two ounces, in a corner of his claim. Watching his opportunity when several persons were near, he artfully uncovered one of the lumps, seeming, at the same time, anxious to conceal it. In a few moments several spectators were eyeing his movements. Soon he turned up two or three more small pieces, and then the larger one. In ten minutes the ground all about him was marked off, and many picks and shovels were employed in prospecting for him, while he went back to his tent, pleased with the success of his maneuver. Several good offers were made him for his claim, and, had he been so disposed, he might have made a good bargain; but he was satisfied with the amount of labor he thus procured. In many cases the grossest impositions have been practiced. Persons have scattered gold in the dirt of a claim they held, then have offered it for a high price, exhibiting a pan full of the rich soil as a specimen. We have now spent many days at Aqua Frio without finding any prospect of success; on the contrary, being involved in debt; and have determined to break up our camp, and, disposing of our tents, cooking utensils, to retrace our steps toward Stockton. One of our company is disposed a little longer to try his fortunes or rather his misfortunes—at the Mariposa mines. Another remains in his lonely grave. All the others, excepting myself, intend to return to San Francisco, and, as soon as they are able, to leave for home.

On Monday, Dec. 10th, we started with a mule train bound for Stockton, which took a few pounds of freight for us, while I packed twenty pounds upon my back. The first day we traveled fifteen miles over the mountains, and saw hundreds going to and from the mines. Burns's tent was so filled with travelers that we were compelled to sleep out in the open air, which was so severely cold that the water froze by our side. The next night we slept at Montgomery's ranch, after walking twenty-three miles.

Spreading our blankets down upon the ground, beneath a canvas roof, we slept so closely packed that no person could have stepped between us. For breakfast we had tea, hard bread, beans, and pork, and a few pickles, for all which we paid $2 each. The following day we traveled in the rain twenty-five miles, fording the Tuolumne. My companions had all dropped behind, half frozen and tired out, seeking shelter and rest in some trading or eating tents we had passed. I pushed on with the mule-train, hoping at night to reach a comfortable shelter; but night found us completely exhausted, and far from any settlement. The company traveling with the mule-train had a tent, but there was no spare room which they could offer me. I had to make up my mind to spend the night alone in the drenching rain, and it was a night I shall never forget. A large log fire was burning, by which I sat till a late hour, when I happened to remember that I had seen a large hollow tree by the road side, at some little distance from our camp. Taking a blazing brand, I went and examined the tree, and found that the hollow would afford my body a shelter by sitting upright, and leaving my feet exposed to the rain. I kindled a fire, collecting some brush and bark with which to replenish it during the night. Then, with the ax I had borrowed, I removed a quantity of dead leaves and filthy rubbish accumulated at the bottom of my cavern. To my alarm, I found among this rubbish fresh marks of a large bear, which had lately found refuge here from a storm such as now drove me to its shelter. But there seemed no alternative, and I thought, besides, that my fire would be a protection against wild beasts ; so I wrapped my blankets about me, and, sinking down into my novel bed, with my feet in a cold bath, I listened to the pattering of the rain, thinking of those far away. Soon my fire began to fail, and I had placed the last piece of bark upon it, and fallen asleep. When I awoke it was pouring in torrents, and my fire was entirely out.

Then came thoughts of the bear, and I instinctively drew in my legs, not wishing to place temptation within his reach, should he be prowling about me. It would not do; I was nearly frozen; the water began to find its way into my bed, which I apprehended I should soon be compelled to share with the old Bruin. Then it was so dark. I got up, took my blankets over my arm, and started to return to the log fire, which I saw dimly burning in the distance. In my haste, I forgot that there was a bend in the bank of the stream below us, making it necessary for me to take a circuit round in order to reach my companions. I soon found myself lodged among the bushes and stones at the bottom of the bank. Then came over me a nervous feeling like a nightmare, and I could already feel myself in the grasp of the grizzly bear - his claws and teeth were in my flesh. Dropping my ax, and every thing but my blankets, and losing one of my shoes, I began an imaginary scramble and flight from my imaginary pursuer. The remainder of the night I passed, wrapped up in my blankets, by the log-fire. A walk of twelve miles the day following brought me to the Stanislaus, where I was to separate from my companions, who had not yet come up—they going on to Stockton, and I to the Stanislaus diggings. The rain continued to pour down. Little dreamed our friends at home of our situation then! With scarcely a dollar in our pockets, a long journey before us, cold, hungry, and wet, our oppressed hearts were ready to sink. Alas! little did I anticipate what a gloomy future was before two of those companions! One of them was the only and the idolized son of his parents, and tenderly and dearly loved by his sisters. His home possessed every comfort and convenience. He had come far from his father's house to perish with hunger. He resolved, "I will arise and go to my father." But that father and that heart-broken mother he was no more to see. A year after we parted - and oh I what a year of suffering and privation must that have been—with that companion of his boyhood and youth, he reached Chagres in most destitute circumstances.

To raise money enough to take him home, he engaged as a boatman on the river, took the fever, and died. In consequence of my recent exposure, I had a severe cold, and was entirely unable to travel ; yet I had no means of paying my expenses at a ranch. Under these circumstances, I crossed the Stanislaus, went to the ranch of Mr. George Islip, a gentleman from Canada, and told him my situation. “Give yourself no uneasiness," he said; "you are welcome as long as you choose to remain with us : all I request of you is that you will feel yourself at home." I passed a very pleasant week with this noble-hearted man, and was treated as a brother. The wind had blown down his house, and torn the canvas roof to ribbons, and we were without shelter from the pelting rain ; but warm fires, kept up in the middle of the temporary shelter, made us comfortable. To protect my body from the rain, I would creep under the table, managing to keep my feet near the fire. After a week of interesting and wild adventure, I was set over the river by my friend, and started for the mines again. The roads were very muddy, and the streams forded with difficulty. In my first day's walk I passed three wagons which were mired—a common occurrence at this season of the year. There were many dead animals by the road side. My Christmas eve I spent most cheerlessly at Green Spring, and the next day reached Woods's diggings.

On the 26th Dec. I visited Sullivan's diggings, Jamestown, Yorktown, and Curtis's Creek. A residence in this portion of the mines was, in every way, more desirable than in the more distant mines at this season. Provisions were cheaper, and there was less danger of attacks from the Indians. All the places I have mentioned, together with the Chinese diggings, Mormon Gulch, Sonora, and others, were a cluster of mines lying near to each other, and between the Stanislaus and Tuolumne rivers.

Return To The Main Page: California Gold Rush: True Tales of the 49ers

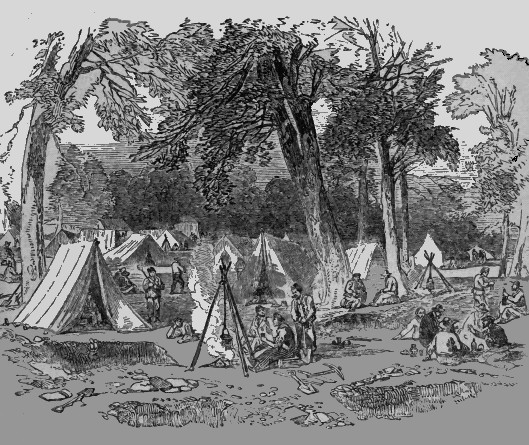

Early Day Miner's Encampment