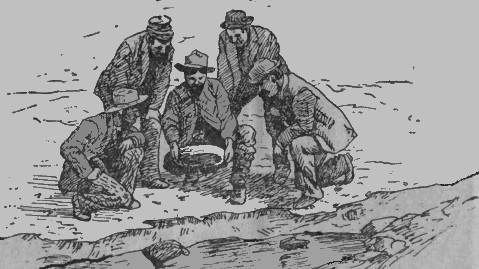

The gold pan was the earliest implement used in separating the precious metal from the accompanying gravel during the California gold rush and is still necessary to the prospector, mill-man, and assayer. Small tools were used to dig in the crevices and to pick up the flakes of gold, and gold pans separated the gravels from the gold. Panning is based on the principle that substances of different densities may be separated by means of water, - with the heaviest materials going to the bottom first. Old time pans were made of the best quality of Russia iron, stamped out of a single sheet, with the edge turned over a stout wire. In modern times, pans made of injection molded plastic are actually more common. The usual dimensions are: Diameter 10 in. at the bottom, 16 in. at top, and about 3 to 4 in. deep. The angle of the sides is 37. The classic method of panning for gold is as follows: The pan is filled with the gravel and sand and then carefully lowered under water and shaken to allow heavier materials to settle; the fine and light material are gradually washed off the top, care being taken not to allow any gold particles to escape; the pebbles and coarser material, after examination, are removed by hand. The process of shaking down the heavies then gently washing the lighter materials off the top continues until only the heaviest materials such as black magnetic sand and gold remains left in the pan.

The pan is then tilted and the water carefully manipulated and when rolled or swirled around the pan, the gold forms a fringe at the front of the sand and is thus collected. The capacity of the pan is so limited that gravel very rich in gold is needed to pay by this method. A skilled operator is able to pan less than one cubic yard of gravel during a day's work. The batea is a cone-shaped wooden version of the miner's pan that was introduced into California at a very early date by Mexican miners. The gold pan is used in all branches of gold mining, either as an instrument for washing, or as a receptacle for gold, amalgam, or rich dirt. It is made of stiff tin or sheet-iron, with a flat bottom about a foot across, and with sides six inches high, rising at an angle of forty-five degrees.

A little variation in the size or shape of the pan will not injure its value for washing. Sheet-iron is preferable to tin, because it is usually stronger and does not amalgamate with mercury. The pan is the simplest of all instruments used for washing auriferous dirt. Some dirt, not enough to fill it full, is put in, and the pan is then put under water. The water ought to be not more than a foot deep, so that the pan may rest on the bottom, while the miner inserts his fingers in and under the dirt and lifts it up a little, so that the whole mass is wet. If the water be deep, the pan may be held in one hand while the other is used to stir up the dirt, but it is more convenient to take both. The dirt having been filled with water, the miner catches the pan at the sides, raises that part toward his body, and lowers the outer edge a little, and commences to shake the pan from side to side, holding it so that all the dirt is under water, and so that a little of the dirt can escape over the outer edge. The earthy part of the dirt is rapidly dissolved by the water, assisted by the shaking of the pan and the rolling of the gravel from side to side, and forms a mud which runs out while clean water runs in. The light sand flows out with the thin mud, while the lumps of tough clay and the large stones remain. The stones collect on the top of the clay, and they are scraped together with the fingers and thrown out. This process continues, the pan being gradually raised in the water, and its outer edge depressed, until all the earthy matter has been dissolved, and that as well as the stones swept away by the water, while the gold remains at the bottom.

Panning is not difficult, but it requires practice to learn the degree of shaking, which dissolves the dirt and throws out the stones most rapidly without losing the gold. If the shaking be too mild and slow, the process consumes too much time ; whereas if it be too rapid and violent, the gold is carried off with the stones. Sometimes the pan is shaken so that the dirt receives a rotary motion. This is the most rapid method of washing dirt, but also the most dangerous. The pan must always be used in cleaning up the dirt which collects in the cradle, in prospecting, and frequently in washing small quantities of dirt collected in other kinds of placer mining. Amalgam can be separated from dirt by washing, almost as well as gold. In panning out, it frequently happens that considerable amounts of black sand containing fine particles of gold are obtained, and this sand is so heavy that it cannot be separated from the gold by washing, while it is easily separated by that process from gravel, stones and common dirt. The black sand is dried, and a small quantity of it is placed in a "blower," a shallow tin dish open at one end. The miner then holding the pan with the open end from him, blows out the sand, leaving the particles of gold. He must blow gently, just strong enough to blow out the sand, and no stronger. From time to time he must shake the blower so as to change the position of the particles, and bring all the sand in the range of his breath. The gold cannot be cleaned perfectly in this manner, but the sand contains iron, and the littler of it remaining is easily removed by a magnet. The blower should be very smooth, and made of either tin, brass or copper.

The pan was made of stiff tin or sheet-iron, with a flat bottom from 10 to 14 inches across, and sides from 4 to 6 inches high, rising outward at a varying angle. It was used mainly for prospecting, and as an adjunct to the rocker, but in the absence of the latter, claims were sometimes systematically worked with it. In 'panning,' as in all methods of placer-mining, the natural gold was separated from earth and stones chiefly by relying on the superior specific gravity of the metal. The pan was partly filled with dirt, lowered into the water, and there shaken with a sideway and rotary motion, which caused the dissolving soil and clay, and the light sand, to float away until nothing was left but the gold which had settled at the bottom. Gravel and stones were raked out with the hand. Except in extremely rich ground, such a process was slow, and it was therefore seldom resorted to, save for the purpose of ascertaining whether it would pay to bring more productive equipment to the spot.

Continue on to:

The Cradle or rocker system for processing gravel

Return To:

Historic Placer Mining Technologies