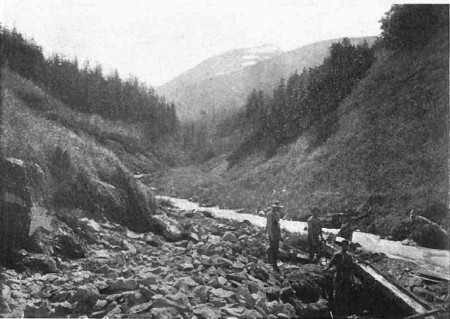

Washing of gravel through the sluice should be carried on as continuously as possible. When processing rich gravels, watches must be set over the sluices, or gold is likely to be missed. As an extra precaution, the sluices should be run full of gravel before shutting off the water. There is no fixed custom regulating "clean ups." Some managers do so every 20 days, others run two or three months, others again clean up but once in a season. In large operations, the first 2,000 feet of sluice are cleaned up every fortnight; the remaining boxes once a year. Sluices are cleaned from the head downward, the blocks being taken up for that purpose. The amalgam of natural gold and quicksilver is collected in sheet iron buckets. The final step is reached when the amalgam is retorted and melted in a graphite crucible. The principle of which the hydraulic miner takes advantage is the great specific gravity of gold as compared with water and rock. To illustrate this quality it may be noted that on a smooth surface inclined at an angle of 1 in 48, subjected to a heavy stream of water, 95 per cent of the fine gold in gravel does not travel three feet. The loss of quicksilver fed into sluices will vary, even under good management, from n per cent to 25 per cent of the amount fed to the sluice box.

Riffle-Bars. The riffle-bars are usually sawn longitudinally with the grain of the wood, but " block riffle-bars " are considered preferable ; the latter are cut across the tree, and the grain stands upright in the sluice-box. The block riffle-bars are three times more durable than the longitudinal ; and as the latter kind are worn out in a week in some large sluices, there is a considerable saving in using the former. The block riffle-bars are only two or three feet long. In some small sluices the riffle-bars are not placed in the boxes longitudinally, nor in sets ; but one bar near the head runs downward at an angle of forty-five degrees to the course of the box, not touching its lower end to the side of the box, but leaving an open space of an inch there. Just below this open space another bar starts from the side of the box and runs downward at right angles to the course of the first bar, and an open space is again left at the end of this bar ; and so on down to near the lower end of the sluice, where there are longitudinal riffle-bars in sets as described in the preceding paragraphs. The consequence of using this kind of riffle-bar is, that though much of the water and light dirt runs straight over the bars, the heavier material runs down from side to side in a zigzag course. Near the head of the sluice is a vessel, from which quicksilver falls by drops into the box; and it follows the course of riffle-bars, overtaking the gold which takes the same route. These zigzag riffle-bars are nailed down. In all sluices, men must keep watch to see that the boxes do not choke ; that is, that the dirt and stones do not collect in one place, so as to make a dam, and cause the water to run over the sides, and thus waste the gold.

There are small sluices, from which all stones as large as a doubled fist are thrown out. For this purpose the miner uses a sluice-fork, which is like a large manure-fork or garden-fork, but has tines which are blunt and of equal width all the way down; the bluntness being intended to prevent the tines from catching in the wood, and the equality of width to prevent the stones from getting fast in the fork. In some sluices, the " block riffle-bars " that is, bars cut across the grain of the tree are set transversely in the boxes, and about two inches apart. Another device is, to fill the pores of such riffle-bars with quicksilver. This is done by driving an iron cylinder with a sharp edge into the surface of the bar, then putting mercury into the cylinder, and pressing it into the wood. The quicksilver, thus fastened in the wood, catches particles of gold, which must be scraped off when the time for "cleaning up" comes. Double Sluices. Sluices are sometimes made double that is, with a longitudinal division through the middle, so that there are two distinct sluice-boxes side by side. Two companies may be working side by side, so that it will be cheaper for them to build their sluices jointly. In some places the amount of water varies greatly ; so that in the winter there is enough to run two sluices, and in the summer only one. -And there are companies which wish to continue washing without interruption; so they wash first on one side and then on the other, and clean up without any interruption to the process of washing. Another device for saving gold in sluices is the "under-current box." There is a grating of iron bars in the bottom of a box, near the lower end of a sluice ; and under this grating is another sluice, with an additional supply of clean water, and with a lower grade. The grating allows only the fine material to fall through 5 and the current of water being moderate, many particles of gold, that would otherwise be lost, are saved. Sometimes the matter from the under-current box is led back to the main sluice.

Rock-Sluices. In the early days, large sluices were frequently paved with stone, which makes a more durable false bottom than wood, and catches fine gold better than riffle-bars. The stone bottoms have another advantage that it is not so easy for thieves to come and clean up at night, as is often done in riffle-bar sluices. But, on the other hand, cleaning up is more difficult and tedious in a rock-sluice, and so is the putting down of the false bottom after cleaning up. The stones used are cobbles, six or eight inches through at the greatest diameter, and usually flattish. A good workman will pave eight hundred square feet of sluice-box with them in a day; and after the water and dirt have run over them for an hour, they are fastened very tightly by the sand collected between them. In large sluices, wooden riffle-bars are worn away very rapidly the expense amounting sometimes, in very large and long sluices, to twenty or thirty dollars a day; and in this point there is an important saving by using the stone bottoms. They are used only in large sluices, and they generally have a grade of twelve or fourteen inches to the box of twelve feet.

The 'long tom' was originally a rough wooden box, about 14 ft. long, and 2 ft. wide at the upper end, and 3 ft. at the lower end. The sides were about 10 in. high and the bottom had six or more cleats or riffles. The water was fed in a continual stream and the flow of water allowed the placer gold gravels to be treated in larger quantities than with the rocker. The next step was the 'sluice-box’, which, as it could be lengthened indefinitely, had a much larger capacity. It is generally made in sections 12. ft. long and from 1 to 2 ft. wide. Riffles are placed both across and lengthwise with the box; mercury is introduced and the gold amalgamated. Three or four pieces of board, an inch wide, are driven inside the big end of the box, four inches from the end, two inches apart to prevent the gold from leaving the box. A run of sluices is composed of twenty or more boxes, one after the other. The longer the run the more gold will be saved. One end of the box is raised two, three, four and sometimes six inches higher than the other end, thereby making one end of a long run several feet higher than the other. The boxes are usually on two stakes, one on each side, nailed together by a piece of board about a foot wide. The boxes must be perfectly tight, so that the water, gold and mercury (quicksilver) can not get out. The pay dirt is put into the boxes with a shovel. The water washes the dirt and gravel out. If there are any large stones that the water will not carry out of the box, a man walking on top of the boxes, throws them out with a long-handled fork. From two to four men can work with a tom; but the amount of dirt that can be washed is not half that of a sluice. The tom may be used to advantage in diggings where the amount of pay-dirt is small and the gold coarse. Historically, the riffle box often contained quicksilver for amalgamation, and as the dirt in it was kept loose by the water falling down on it from the riddle above, so a large part of the gold was caught; but where the particles of gold were fine, much must be lost.

Continue on to:

Dry and Underground placer processing methods used historically

Return To:

Historic Placer Mining Technologies