In these days when, owing

to the high price of precious metals, so much attention is being turned

towards silver and gold mines, too much care cannot be taken by those

investing or acting as examiners or experts in gold mines, that there are no

tricks played upon them by the astute miner; for "for ways that are dark and

tricks that are vain" the western miner is at times "peculiar." One of these

tricks is what is known as "salting" mines or ledges ; that is, by various

means and ways introducing into the mine or into the samples taken from it,

certain rich minerals which do not rightly belong by nature in the mine or

property, in order to raise the value of the mine in the eyes of the

investor or expert. When samples are taken from such a tampered-with mine

the values and results must be accepted “cum grano salts”, with a very large

grain of salt indeed. Whether this classical allusion be the origin of the

word "salting" we do not know.

"Take care you ain't salted" is the advice to the inexperienced investor or

novice expert. So clever are the miners, that cases are on record where even

a most experienced expert has been taken in, and comparatively, or wholly

valueless properties sold for large sums, the purchase followed later by

woeful dismay and surprise, when dividends were called for and did not

appear.

Gold mines of all others, are the most easy to salt, hence the precaution in these days is timely. Whilst a mining engineer or expert can hardly prevent salting, with care he can, and ought to be able to avoid being taken in; to be forewarned is to be forearmed. On entering a mining camp in the far West, especially in the more remote outlandish districts, an investor or an expert, may consider that the whole village, from the hotel bell-boy to the mayor, (who, by the way may be the principal saloon keeper) is in league against him. Directly he arrives, everybody in town wants to know his business; on this he should keep as mum as possible, and, if he can, throw impertinent inquirers off the scent. The idea is, "Here is a capitalist to fleece and an expert to delude." Every one, too, has a "hole in the ground" of his own to present.

Should they get wind of the particular property in view, there are confederates and middlemen anxious to share the spoils. Moreover, it is considered to the general credit of the camp to sell a mine, be it whose it may, good or bad, and if you mention any property, you will invariably hear it "cracked up." The eastern "tenderfoot" is somewhat of a "sheep among wolves" in such a camp. The expert, too, is at a certain disadvantage on entering into a strange mining camp, not being familiar with the local conditions. Ores for instance in one section or region are not always of the same value as similar ores in another, the rocks may look new and strange to him, and there are a hundred local conditions known only to the resident miner. It would be well, when possible, for an expert, before passing a decided opinion on an important property, to stay around in the vicinity for a while till he knows the "hang of things." On his way to the mine there will be plenty to fill his ears with the untold value of the property he is about to examine, this friendly duty is not infrequently performed by an officious middleman. To favor and "soften up" the expert's mind and heart and make him "feel good" toward the property, attentions of all kinds are showered on him. He is driven about town like a nabob, and if he shows a weakness for a "wee bit o’ drink," champagne and whiskey are at his service ad lib., as judicious preparation for the coming examination. It may be observed here, that attempts are made sometimes to "salt" the expert as well as the mine, not merely by befuddling his brain with intoxicants, but by offering bribes, and as an expert is often not too well off, the latter is a great temptation. We will now suppose, after this ordeal, he goes to the mine with the superintendent or miner. All may be, and we may say generally is, honest and square, or it may not.

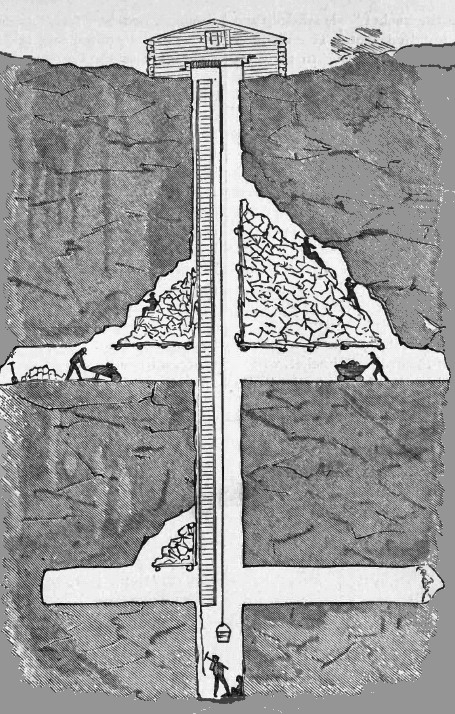

The expert looks over the exterior and surface signs of the property, studies the outcrop of the vein on the surface, its probable surface continuity, the advantages and disadvantages of the situation of the mine, its proximity to railroads, smelting works, markets, etc., and then enters the mine in company with the miner. As a rule the latter will naturally point out to him the richest portions and ignore the poorer; sometimes he excuses himself from taking him down into the latter because it is dangerous or full of water. If full of water the expert if possible should have it pumped out. He may suggest here and there, that such and such a spot would be a good one for the expert to take his samples and so forth. The expert of course assents to all he is told, but with one eye open, and does not stop to take any samples for assaying until he has seen the whole of the mine, then he requests his companion to go out on the dump and smoke his pipe there, as he insists upon having no one with him in the tunnel when he is taking his samples for assay. He will be inclined to rather avoid those particularly favorable spots suggested to him by the miner, as probably giving too rich an average for the general run of the mine, or as not impossibly being "fixed" for him. If he suspects the latter, he will take a sample or two to see if the mine has been tampered with, taking a little of this out on the dump crushing it and washing it in an iron spoon. If a very astonishing amount of gold colors show up, his suspicions are aroused. The judicious miner does not generally want to salt too heavily, for fear of the enormous results exciting suspicion, but despite his care he nearly always salts a little higher than he intended. In a mine where the rock is hard, a miner may salt by drilling holes and inserting mineral or ore and disguising the hole.

In loose ground or one full of cracks, a shot-gun loaded with a moderate discharge of gold-dust will do the work. The skill of the miner in this case lies in his choice of a spot where he thinks it probable the expert will take samples, or in coaxing the expert to take samples from such ground. In hard ground the expert may avoid such salting by having the work blasted out in his presence till a purely fresh, virgin face is shown and then taking his sample. These precautions are not necessary under all circumstances, but only in such cases where the expert has a suspicion that there is an attempt to "put up a job" on him. After getting his samples, and as many as possible, he will sack and seal them then and there in the mine, and never lose sight of them till he has expressed them to his own home. Sometimes a mine is so timbered up, that sampling is difficult. Now as they go down the shaft, it may be the expert remarks "I should like to take a sample in this shaft, but it is so timbered up that I don't see how we can do it without ripping out some of these boards." "Why of course, so you oughtter" says the miner, "and see here, I think this board is loose." Now beware lest that board was purposely loosened and behind it the ground is salted. By taking a great number of samples at comparatively close intervals, provided afterwards the samples are not tampered with, the expert is less liable to be deceived by salting, than if he took very few. A mine cannot be salted all over from end to end if it is a large one, only at judicious intervals, and it will be hard if the expert does not escape some of those intervals and get some true samples.

Besides taking his regular assay samples by cutting all around the walls, roof and floor of the tunnels at intervals of five, ten, or twenty feet, according to circumstances, crushing, and quartering the debris, and finally sacking and sealing his sample bags, he should occasionally take a "grab sample," or a bit of rock at random, or a small sack full from the great mass of his sample, and put them in his coat pocket, and keep them on his person, to act as a reference in case of any possible tampering or accident to his samples whilst in the vicinity or in transit. He should also take bulk samples, good sized chunks of uncrushed rock which should agree with the assay results of his quartered samples. A disadvantage an expert is under in a strange camp, if he cannot take his own assistant with him, is, that he is very much at the mercy of the miner, if any hard work has to be done, such as blasting or hard digging. Whilst engaged in such work the miner, if he pleases, has many chances of scattering around a little gold-dust on the rock of the vein or the loose dirt of a placer.

Whilst gold-dust is the favorite medium for salting a gold mine, chloride of gold is sometimes used. The latter, however, is rather a dangerous and barefaced trick to try on a competent expert, as its quality can readily be detected by the chemist, it being soluble in water. In a case of this kind that came to our knowledge, an experienced expert had examined a certain mine and condemned it. Later, the owner who was an honorable man, asked him if, as a special favor, he would re-examine it, as in his absence the assay values from the mine had of late shown much better results. The expert reluctantly consented to do this, though contrary to his general rule. In going along the workings he noticed here and there on the walls, certain patches and streaks of clay or mud, he had not observed on his first visit. Guessing what they were, he casually observed to the miners, "Seems to have been raining in the mine since I was here." However to the great delight doubtless of the miners he took several samples of these, and forwarded them to a reliable chemist. The latter pronounced them chloride of gold. This of course gave the salting scheme away as chloride of gold does not occur free in nature, much less in a mine. The owner of the mine was exceedingly angry when he learned what the miners had done without his knowledge or connivance. The men themselves being commonly more or less interested in the sale of a mine, are apt to try and salt it without any connivance of the owner or superintendent. We heard of a case in the San Juan district where a mine that was fairly good was about to be examined. This mine carried occasionally specimens of the very rich ore, called ruby silver. Not satisfied with the fair, natural richness of the mine, the miners must needs import into the hole, quantities of ruby collected from other mines in the district, whose men were of course in sympathy with the scheme and probable sale. This was acting without the knowledge of the owners.

SALTING GOLD PLACERS:

Although a gold placer usually covers a very large area of ground, it is

possible to salt it. Usually a miner shows up his placer by opening up pits

at convenient intervals, so as to cover the property. Nothing is easier than

to salt these pits with gold-dust. Consequently whilst an expert will

examine these holes and pan the dirt, he should be on his guard, and insist,

where possible, on holes being freshly dug in his presence. Even then he is

not safe. Generally in a placer, by the cutting of a stream, sections are

shown sometimes from grass roots to bed rock. From such he should take and

pan samples at different levels in the exposure, this too, privately and

without too much supervision of the interested miner.

Continue on to:

Gold Prospecting Basics, Part I

Return To:

Gold And Silver Basic Prospecting Methods