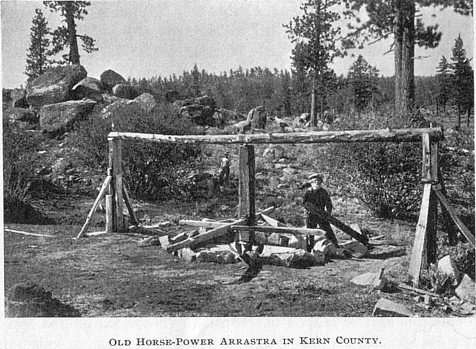

The Arastra and Chilean Mills:

To extract the

gold from quartz vein material, the

rock must be crushed. Historically, quartz was pulverized either in an

arastra, or Chilean mill, or by stamps. In modern times, ball mills are

used. This article principally discusses the arastra, the oldest rock

crusher that had general use. The arastra is the simplest instrument for

grinding auriferous quartz. It is a circular bed of stone, from eight to

twenty feet in diameter, on which the quartz is ground by a large stone

dragged round and round by horse or mule-power. Handed down through the

centuries, the primitive arastra is still useful in certain contingencies.

It is like a cider mill or a bark mill in its principle, and was probably

suggested by recollections of that machine, or else of the Spanish

wine-press. The contrivance is run by means of a horse walking round in a

circle, hitched to the arm of an upright shaft, which revolves slowly

around. The foot of this shaft runs in a box or place prepared for it, on a

timber imbedded into the ground.

A circular, shallow pit, a dozen feet or more in diameter, is first paved with hard, uncut stones of granite, basalt, or other hard rock. This pavement is a foot thick, and beneath it is a bed of puddled clay 6 inches deep. A vertical shaft with an arm, or arms, revolves in the center of the arastra. Two or more large stones, with one flat side to each, are selected, and fastenings made in them for ropes or chains, by which they are securely fastened to the arms of the shaft, one on each side, opposite each other, with their flat sides resting on the pavement below. These are intended to drag round on top of the paved bottom. Grinding blocks weighing 400, or perhaps even 1,000 pounds, are fastened to the arms by chains or rawhide strips. The forward part of each stone is raised a couple of inches off the floor. Mule, horse, water or steam power may be used, the speed ranging from 4 to 18 turns a minute. When they are propelled by water-power, and attached to a water-wheel they are driven somewhat faster. Nothing can be simpler, less expensive, or save a greater proportion of the value in the ore than the arastra. Its limited capacity is its worst fault. An arastra 10 feet in diameter will treat 500 or 600 pounds of ore at a charge, and handle one ton a day of 24 hours. Ores that were so poor they yielded nothing to the stamp mill have paid well with the arastra.

There are two kinds of arastras, the rude or improved. The rude arastra is made with a pavement of unhewn flat stones, which are usually laid down in clay. The pavement of the improved arastra is made of hewn stone, cut very accurately and laid down in cement. In the center of the bed of the arastra is an upright post which turns on a pivot, and running through the post is a horizontal bar, projecting on each side to the outer edge of the pavement. On each arm of this bar is attached by a chain a large flat stone or muller, weighing from three hundred to five hundred pounds. It is so hung that the forward end is about an inch above the bed, and the hind end drags on the bed. A mule hitched to one arm will drag two such mullers. In some arastras there are four mullers and two mules. Outside of the pavement is a wall of stone a foot high to keep the quartz within reach of the mullers. About four hundred pounds of quartz, previously broken into pieces about the size of a pigeon's egg, are called a "charge" for an arastra ten feet in diameter, and are put in at a time. The mule is started, and in four or five hours the quartz is pulverized.

Water is now poured in until the powder is thoroughly mixed with it, and the mass has the consistence of thick cream. Care is taken that the mixture be not too thin, for the thickness of it is important to the amalgamation. The paste being all right, some quicksilver (an ounce and a quarter of it for every ounce of gold in the quartz, and the amount of gold is guessed at from the appearance of the rock) is scattered over the arastra. About a tablespoonful to every five tons of gravel when treating tailings, has been found a satisfactory proportion in California. The grinding continues for about two hours more, during which time it is supposed the quicksilver is divided up into very fine globules and mixed all through the paste (which is so stiff that the metal does not sink in it to the bottom), and that all the particles of gold are caught and amalgamated. After the machine has been started, and a little water added from time to time, little else need to be done for four or five hours, and this is perhaps one of the reasons for which it has always been so favored in Mexico. After the run, the amalgamation having been completed, some water is let in three or four inches deep over the paste, and the mule is made to move slowly. At this stage, the quartz and ore will be very finely pulverized, and water should be added until the pulp is as thin as cream. The paste is thus dissolved in the water, and the gold, quicksilver and amalgam have an opportunity to fall to the bottom.

A half an hour of this treatment suffices and the thin mud is run off, leaving the gold and amalgam on the floor of the arastra. A second charge of broken quartz is put in, more mercury added to the mixture, and the grinding operations are repeated. The clean-up does not take place oftener than every ten days, and sometimes only at intervals of a month or so. The length of a "run," or the period from one cleaning up to another, varies much in different places. In the rude arastra a run is seldom less than a week, and sometimes three or four. The rougher the bottom, the longer the interval between clean-ups, as all the stone work must be taken up each time and all the sand and mud between them must be washed carefully. During the operations, the amalgam settles down between the paving stones, so that the bed must be dug up and all the dirt between them carefully washed. In the improved arastra the paving fits so closely together, that the quicksilver and amalgam do not get down between them, but remain on the surface, and can readily be brushed up into a little pan, and therefore cleaning up is much less troublesome and is more frequently repeated than in the rude arastras; besides there is a greater need of frequent cleaning up in the improved arastras, because the amount of work done within a given time is usually greater.

The arastra is extremely valuable to the poor man who, having discovered a gold-bearing vein, wishes to transfer some of the metal into his own pocket, at the least possible outlay. Its cheapness places it within reach of all, while a stamp will cost a good deal. Then again the amalgamation being more perfect in the arastra than in any other mill, it is particularly suited for the poor, lean ores. It is, however, only adapted to those that are free-milling, others not being suited to this form of apparatus, nor, indeed, to any save very costly plants. Some arastras have been built to treat old tailings, and have paid well when water power could be used. Free-milling gold and high-grade silver and gold ores are those usually treated. The arastra is a slow instrument, but in some important respects it is superior to any other method of working auriferous quartz. It grinds the quartz well, is unsurpassable as an amalgamator, is very cheap and simple, requires no chemical knowledge or peculiar mechanical skill in the work, requires but little power, and very little water all of them important considerations. In many places, the scarcity of water alone is enough to enable the arastra to pay a larger profit than any other method. The arastra is extremely valuable to the poor man who, having discovered a gold-bearing vein, wishes to transfer some of the metal into his own

pocket, at the least possible outlay. Its cheapness places it within reach of all. Additionally, if a miner finds a rich spot in a lode, he may be doubtful as to the amount of paying rock which he can obtain. Such cases very frequently happen in California, and the arastra is just the thing for the case; for then if the amount of paying rock is small, nothing is lost, whereas the erection of a stamping-mill would cost much time and money, and before it could get into smooth operation the rich rock would be exhausted, and the mill perhaps become worthless. No other simple process of amalgamation is equal to that of the arastra ; and it has on various occasions happened in California, that Mexicans making from fifty to sixty dollars per ton from quartz, have sold out to Americans who have erected large mills at great expense, with patent amalgamators, and have not been able to get more than ten or fifteen dollars from a ton. The arastra is sometimes used for amalgamating tailings that have passed through stamping-mills.

When constructing an arastra, the flagging should be of tough, coarse rock; granite, basalt or compact quartz are all good. This flagging should be at the very least a foot thick. When the arms of a l0 foot diameter arastra are revolving 14 times a minute, the outer stone is traveling 400 feet a minute. Round holes closed by wooden plugs, or a side gate, lets the liquid mud out. Some mill men use chemicals in the arastra; potassium cyanide, and wood ashes or lye are probably the most useful, as the latter cuts grease and the former gives life to the quicksilver. Rich silver ores are treated with blue stone (copper sulfate) and salt. A 12-foot arastra will never treat more than two tons a day, and often no more than one-half that. One man a shift can look after a couple of arastras, and the owner, in case of one arastra that is working on tailings, often does everything himself. Overshot wheels, or turbines, or hurdy-gurdies, furnish the power to operate them in many cases. A simple mule-powered arastra may be built for a very low price.

The Chilean or Edge Mill. The Chilean mill has a circular bed like the arastra, but much smaller, and the quartz is crushed by two large stone wheels 3 to 6 feet in diameter standing on their edges which roll round on their edges. In the centre of the bed is an upright post, the top of which serves as a pivot for the axle on which both of the stones revolve. A mule is usually hitched to the end of one of the axles. This is a machine which is commonly used for grinding cement. For Processing gold ores, the methods of managing the rock and amalgamating with the Chilean mill, are very similar to those of the arastra. The Chilean mill, however, was rarely used in California; the arastra being considered far preferable.

One of the later ideas which was once in vogue as a part of stamp milling operations was to employ Chilean mills as intermediate grinders following stamps. This was with the viewpoint that the tube-mill finds its greatest efficiency in reducing 30 or 40-mesh material to 200-mesh, the Chilean mill in medium grinding, and the stamp in coarse crushing. With this idea it has been proposed to use heavy stamps crushing through a 4 to 12-mesh screen, delivering to Chilean mills grinding through a 30 or 40-mesh screen to tube-mills sliming to the desired fineness. However, there has come contemporaneously with this idea a rapid increase in the weight of stamps and a development of tube milling to cover a wider range. As a result it is recognized that stamps harnessed to tube mills make a combination crushing by impact that is so efficient that the introduction of intermediate grinding mills is inadvisable. The Chilean mill has been used in this way to increase or double the capacity of existing mills without erecting more ore-bins and stamps, by being placed after the stamps or between them and the tube mills. The same result can be affected by adding more tube mills. A tube or ball mill is a modification in which a large number of small balls are placed with finely divided ore in an iron cylinder which can be revolved.

Continue on to:

Stamp Mills

Return To:

Hard Rock Quartz Mining and Milling