The supremacy of the stamp-mill for crushing gold and silver ores and the reason why for so many decades it so successfully withstood the attempts of both theoretical and practical men to supersede it or limit its application, lie mainly in its simplicity, reliability, and wide range of adaptability. The modern gravity-stamp has been evolved from the mortar and pestle used by primitive man, and has remained simple in principle and construction. At first sight it appears to be a crude machine. All is done by gravity. There is an absence of the elevating, conveying, and reworking, which give so much trouble in the other systems of milling. Its range of adaptability is far greater than that of any other crusher. It is used in Gilpin county, Colorado, in the treatment of a gold ore slow to amalgamate, with its crushing capacity subordinated in the effort to give the ore the particular treatment required to save the gold, the daily output being reduced to one ton per stamp. In South African practice amalgamation is subordinated to crushing, resulting in a daily capacity as high as ten to twenty tons per stamp. The stamp is used for disintegrating cemented gold bearing gravel and for pulverizing the softest rock, as well as for crushing the hardest and toughest quartz. It may be fed with fine material having only sufficient grit to keep the shoes from hammering the dies, up to slabs of rock the size of a large meat-platter and 3 to 4 in. thick. Such rock is often sent through the battery during a break-down of the rock-crusher. It will crush wet or dry. It will deliver its product through a 4 or a 40-mesh screen, or through a still finer one if desired, though the modern stamp-battery is not adapted to crushing to advantage through a screen finer than 40- mesh. No machine can compare with it in amalgamating, or in preparing an ore for concentration, except where the extremely friable nature of the material requires stage-crushing; yet it has made an enviable record in crushing and preparing pyritic copper ore for the concentration of its sulfide.

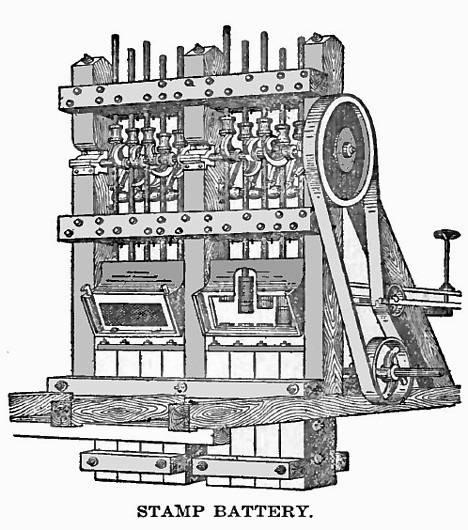

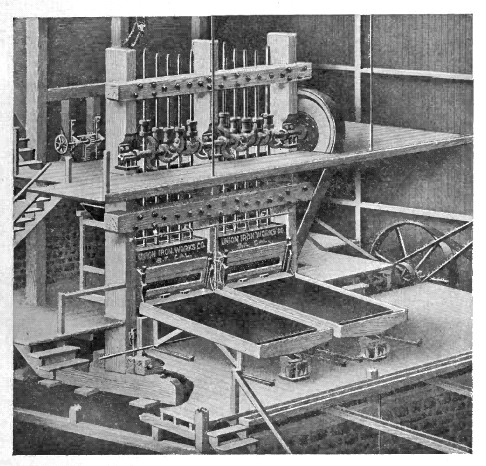

Historically, ninety percent of the quartz crushed in California and most of the western US was pulverized by stamps, of which there are two kinds, the square and rotary. The square stamp has a perpendicular wooden shaft, six or eight feet long, and six or eight inches square, with an iron shoe, weighing from a hundred to a thousand pounds. The wooden shaft has a mortise in front near the top, and a cam on a revolving horizontal shaft enters this mortise at every revolution. When the cam slips out of the mortise, the stamp falls with all its weight upon the quartz in the "battery" or "stamping-box." The rotary stamp has a shaft of wrought iron about two inches in diameter, and just before falling this shaft receives a whirling motion, which is continued by the shoe as it strikes the quartz. The rotary stamp is considered superior to the square, its advantage being that it crushes more rock with the same power, that it crushes more within the same space, and that it wears away less of the shoe in proportion to the amount of rock crushed. There are usually half a dozen square stamps or more, standing side by side in a square-stamp mill, and these do not all fall at the same moment, but successively, running from the head to the foot of the "battery." The quartz is put in at the head of the battery, and is gradually driven to the foot. The rotary stamps sometimes stand side by side, and sometimes in a circle. The battery of both rotary and square stamps is surrounded by wire gauze, or a perforated iron plate, which allows the finely pulverized quartz to escape, yet retains the coarser particles. Quartz is crushed wet and dry. In wet crushing a little stream of water runs into the battery on one side and escapes on the other, carrying all the fine quartz with it.

Separation.

After pulverization comes the separation of the gold from the rocky portion

of the powder. The means of separation are mechanical or chemical. The

chemical process is amalgamation; the mechanical are those wherein the gold

is caught on a rough surface with the aid of its specific gravity. The chief

reliance is upon amalgamation, and in some large quartz-mills mechanical

appliances are not used at all for catching the particles of gold, but only

for catching amalgam. The mechanical appliances used in quartz-mills in

separating the gold from the pulverized rock, are the blanket, the sluice,

and the raw hide. The blanket is a coarse, rough, gray blanket, which is

laid down in a trough sixteen inches wide and six feet long. The pulverized

quartz is carried over this blanket by a stream of water, and the particles

of gold are caught in the wool. The blanket is taken up and washed, at

intervals depending upon the amount of

gold deposited. In some mills' where a large amount of rock

is crushed, and where the powder is taken over the blanket before trying any

other process of separation, the washing takes place every half hour. In

mills where the pulverized quartz is exposed to amalgamation first, the

blanket may be washed three or four times a day. The washing is done in a

vat, kept for that especial purpose.

The sluice used in quartz-mills is similar to the placer board sluice, but the amount of matter to be washed is less, and there is no dirt to be dissolved, and there are no larger stones, and therefore the sluice is not so large, so strong, or so steep in grade, as the placer-sluice, and the riffle-bars are not so deep. In some quartz-mill sluices there are transverse riffle-bars. If the quartz has much pyrite or chalcopyrite, the sluice is used to collect this material and save it for separation at some future time. The pyrites ordinarily contains, or is accompanied by much gold, which it protects from amalgamation. This separation of the pyrites from the pulverized rock is called "concentrating the tailings," and the material collected is called " concentrated tailings." In the sluices of some quartz-mills cast iron riffle-bars are used ; cast in sections about fifteen inches square, and about an inch deep. Much study has been devoted to the subject of making these rifflebars in such a manner that the dirt will not pack in them, but will always remain loose, and keep in constant motion under the influence of the water running over them; but the object has never been fully attained.

Quicksilver is used in nearly all quartz-mill sluices. The raw hide used in separating gold from the pulverized quartz is a common cow hide, laid down in a trough with the hairy side up, and the grain of the hair against the course of the water. The gold is then caught in the hair. Sheep hides have been used in the same manner, recalling to mind the Golden Fleece. The hides, however, are inferior to the blankets for this purpose, and are never used in the best mills. The methods of amalgamating are numerous. Among them are amalgamation in the battery, amalgamation with the copper plate, amalgamating bowls, and patent amalgamation of many kinds. In many mills quicksilver is placed in the battery, two ounces of quicksilver for one of gold ; and about two-thirds of the gold is caught thus. The copper plate in quartz-mills is made in the same manner as in placer-sluices, under which head a description of the plate may be found. Some amalgamating bowls or basins are little Chilean mills and arastras, made of cast iron. One plan of amalgamation is to use a cast iron bowl about four feet in diameter and a foot deep. Near the bottom are horizontal iron arms, which revolve and stir the quicksilver and pulverized quartz together. Four or five of these bowls sit in a row but at different levels: the bottom of the first bowl being level with the top of the second, and so on. The pulverized quartz passes through them all. Under each bowl a fire is kept up, because heat forms the action of amalgamation. If there be any pyrites in the quartz, some common salt is thrown in to assist in releasing the gold from the embraces of the sulfides, and preparing it to be seized by the mercury. Another amalgamating bowl revolves on an axis that stands at an angle of about seventy-five degrees to the horizon, so that the material in the bowl is continually moving; and the bottom is divided by little compartments, which make a constant riffle. In other bowls the pulverized quartz is forced with water through the mercury. The methods of amalgamation differ very much, and a book might be filled with a description and discussion of the processes used at different quartz-mills in California.

Sulfides.

Many auriferous quartz veins contain considerable quantities of sulfides

or

pyrites of iron, copper and lead, and their presence prevents

amalgamation, and thus causes a great loss of gold. It is said that on some

occasions in good mills, not more than twenty or thirty dollars have been

obtained from a ton of vein stone which had seven or eight hundred dollars

of gold in every ton. The best method of treating the quartz containing

pyrites, is to roast it, and thus drive off the

sulfur, but this process is so expensive that it is seldom used ;

and the common practice is to crush and amalgamate the rock, and save the

concentrated tailings for some future time, when there may be a sale for

them, or when it will be cheaper to reduce them. The pulverized sulfides are

decomposed by exposure to the air, and after the tailings have been

preserved for a time, they may pay better at the second amalgamation than at

the first. A mixture of common salt assists the decomposition of the

pyrites.

Early Day Quartz Stamp

Mills.

The most productive quartz-mill during the 1850s and 1860s, in the state

of California was the Benton mill, on Fremont's Ranch, in Mariposa County.

It was also the largest, having forty-eight stamps. There were four mills on

the estate, with ninety-one stamps in all, and their average yield per month

is sixty thousand dollars. A railroad four miles long, conveys the quartz

from the lode to the mills. The Allison quartz mine in Nevada County,

produces forty thousand dollars per month. The Sierra Buttes quartz-mill,

twelve miles from Downieville, yields about fifteen thousand dollars per

month. These last mills run night and day, and crush and amalgamate ten

thousand tons of rock a year, or twenty-eight tons per day. Forty men are

employed, twenty-five to quarry the rock, five in the mill to attend to the

stamps and

amalgamation, one to do carpentry, one for blacksmithing, and eight

for getting out timber, transporting quartz, and so forth. The cost of

quarrying, crushing and amalgamating a ton of rock, is six dollars. The

wages of the men are from fifty to seventy dollars per month with boarding.

The average wages is sixty dollars. About ten miles eastward of Sonora, in

Tuolumne County, are some rich veins of auriferous quartz, the most

prominent of which are the Soulsby and Blakeslee lodes. The Soulsby mill

produced forty thousand dollars in three weeks, when it commenced work in

1858, and continued to be profitable for many decades afterward.

Mill Operators:

The men who are in charge of stamp mills are almost invariably good mill

mechanics, a large part have graduated out of machine shops, and even the

least of them are first-class 'monkey-wrench' machinists, but only a small

part are metallurgists. The methods of many of them are those that they were

taught, and these methods they apply to all conditions with but little

variation. This lack of ability to initiate experiments, to test, to devise

new methods, and to progress, has hampered the advancement of the stamp-mill

process. It is seen in the tenacity with which they cling to the old-time

idea of saving the maximum amount of gold in the mortar, when the same and

in some cases a higher saving could be obtained by giving the stamp-battery

a chance to perform its proper function to prepare the ore for amalgamation,

rather than to amalgamate it. Wherever the mill men have forsaken the

well-beaten path of trying to save all the

gold possible in the mortar, the tonnage has increased and

ease of operation has been promoted. "Catch the gold as soon as you can

catch it inside the mortar,” is a good old maxim, but the slogan of the mill

man should be, "Down with the tailing and up with the tonnage," and not,

"Increase the inside catchment keep it up to 60 or 80 or 95%." The mill man

should understand adjusting the mill to the peculiar requirements of the

ore, that he may be able intelligently to put his slogan into actual

practice. Pie should also be able to determine the point where a higher

tonnage ceases to be desirable by reason of resulting in too high a tailing,

the economic limit having been reached.

Return To:

Hard Rock Quartz Mining and Milling