Outstanding among the lode deposits of the Sierra Nevada is the Mother Lode system of gold deposits, a strip of mineralized rock 1 to 4 miles wide that extends 120 miles along the lower western flank of the Sierra Nevada. From near Georgetown in El Dorado County it extends southward to Mormon Bar, 21 miles southeast of Mariposa, in Mariposa County. The five counties it traverses: El Dorado, Amador, Calaveras, Tuolumne, and Mariposa-are often referred to as the Mother Lode counties.

The quartz veins are large tabular masses of quartz that strike northwest and dip northeast. Though they appear to be locally conformable with the country rock at the surface, the veins cut across various units of the country rock along the strike and down the dip. Individual veins, as much as' 50 feet thick and a few thousand feet long, are localized in systems of parallel or sub-parallel lenses with blunt ends, some of which fray out into stringers. The vein mineralogy is simple. Milky quartz, the predominant vein filling, is characteristically ribboned, different layers having been deposited at different times. A small amount of sulfides, mostly pyrite, accompanies the quartz. Gold occurs in the free state, commonly in steeply pitching shoots where the veins bulge or at junctions and in stringer lodes. The gold is interstitial with the quartz and the sulfides.

The ore bodies in country rock are of diverse types, but the mineralized greenstone, known as gray ore, and mineralized schists are the most productive. The mineralized greenstone is composed of ankerite, sericite, albite, quartz, and 3 to 4 percent pyrite and arsenopyrite. It is interlaced with veinlets of quartz, ankerite, and albite. Gold is intergrown with the sulfides or is interstitial with quartz. The mineralized schist ore bodies are composed chiefly of ankerite and subordinate sericite, pyrite, quartz, and albite. Free gold is associated with pyrite. Flanking the main vein system of the Mother Lode on the east and west are two additional zones of mineralization known as the East Belt and West Belt. These belts are shorter and less continuous than the Mother Lode and may be separated from it by 5 to 15 miles of unmineralized country rock; nevertheless, they are similar to it genetically and mineralogically and many authors have considered them as Part of the Mother Lode. In production reporting, however, the East Belt and West Belt have been considered as being districts separate from the Mother Lode; so to avoid confusion, this distinction is also made in this report.

Distribution of Gold in Quartz.

The rich quartz-veins of California extend from Kern River to the

Siskiyou, are found on hills, in canons and in vales. They are at least two

thousand feet above the level of the sea, and not more than ten thousand

feet above it. Their course is generally from north-north-west to

south-south-east, and they dip steeply to the eastward, sometimes being

nearly perpendicular. They differ in thickness from a line to sixty feet.

Quartz veins are very numerous in most of the mining districts, so the task

is not to find the veins, but rather to find those which are

gold-bearing. It is supposed that nearly all large veins come

to the surface of the bed-rock or "country;" but many of them are covered

with soil and thus are hidden. Hidden veins are called "blind;" those

plainly visible on the surface are called" croppings veins," because their

position is shown by the out-croppings. Experience has not ascertained

whether large or small veins are more likely to contain gold. It is found in

both. The porous quartz, or that containing many cavities, is more

frequently found auriferous and richly auriferous, than the very compact

quartz. The best gold-bearing veins are usually yellowish or brownish tinge,

near the surface at least; but very rich specimens are found in white and

bluish-white rock. Most quartz veins in California contain a little gold;

the metal seems to have been distributed most lavishly, but unfortunately in

nine-tenths of the veins, the proportion of metal is too small to pay. Most

of the large veins are supposed to run for miles upon miles, though they can

rarely be traced clearly on the surface for more than a furlong. The

auriferous veins vary much in richness. No vein is wrought for more than a

few hundred feet. Beyond that, it is either too poor to pay, or the vein is

hidden. Some persons have supposed that there is one great gold-bearing

quartz vein running along the side of the Sierra Nevada, from Mariposa to

Plumas county, and that many of the richest claims are really in this one

vein; but this a supposition which cannot be proved now. Sometimes a vein

seems to spread out and divide into a number of smaller veins, all of which

afterward unite again. These points of junction, and the narrower places in

the vein, are usually richer than other parts of it. When two veins cross

each other, one may be auriferous on one side of the intersection and not on

the other; but in this case the other vein will be auriferous on both sides.

It is as though they were streams, one rich, the other barren, and that

after meeting, the wealth of the one was divided between them. It is a

general rule that metalliferous veins running parallel with the strata of

the bed-rock or country are not extensive. In fact they are rather deposits

than veins, and though often extremely rich are soon exhausted, while the

lodes which run across the stratification, run far and deep, and have a

regular and straight course and dip.

Lodes lying between two different kinds of rock, are usually richer than those which have the same kind of rock on both sides. Thus it is said that the richest veins of auriferous quartz in California, have been discovered at the intersection of trap and serpentine, and the richest places in veins are where they cross from one kind of bed-rock into another. The richest part of a lode of auriferous quartz is almost invariably on the lower side of the vein, near the foot-wall. All these are facts to be remembered by the prospector as a guide, and an assistance to him in his search for a rich gold-bearing vein. If the lode is covered with earthy matter, he may sometimes trace its course by the difference in the color of the dirt and stones over it from that elsewhere. When the prospector finds dirt and stones on a vein, evidently disintegrated portions of it, he should wash some of the dirt in a pan, and if he finds no gold, there is a strong presumption that the vein is barren.

Prospecting Quartz Rock.

After finding a gold-bearing vein, the question arises whether it will

pay. Great sums are lost in gold-mining countries by injudicious investments

in mills and machinery to work the auriferous rock, and persons going into

the business should be particularly careful not to commit this great error.

The business of quartz mining has great profits, but also great pecuniary

dangers connected with it. It, is rarely that all the rock of a vein will

pay for working. In some lodes, the veinstone will average one hundred

dollars to the ton, for all the stone found in a certain part of the lode,

but beyond that the rock may be poor or worthless. Picked specimens may be

worth several thousand dollars to the ton, but perhaps not more than a ton

of such specimens has been obtained in the best lode ever opened in the

state. The most profitable lodes are those that have a large supply of rock,

easily to be obtained, and all of it yielding something above the cost of

working. The common method of ascertaining whether rock will pay, is to

pulverize a little of it and wash it in a horn spoon. In taking out the

quartz rock in large lodes, it is important to take out only that which will

pay, and to determine this, the superintendent of the quarry-men must

occasionally test the vein-stone. He takes several .little pieces of it,

average specimens, places them on a hard, smooth, flat stone, about a foot

square, on which he crushes them with a stone muller four inches square, and

then by rubbing with the muller he reduces them to a fine powder. He has a

horn spoon, made of a large ox-horn, with a bowl about three inches wide,

and eight inches long, being merely one-half of the horn in its natural

shape. With this spoon he washes out the powder in water, and if he does not

find a speck of gold or a "color," as it is called, in a pound of the rock,

he infers that it will not pay. The three principal quartz mines in the

state are those of Fremont in Mariposa county, of the Allison company in

Nevada county, and of the Sierra Butte company in Sierra county. The first

has produced $75,000 in a month, the second $60,000, and the third $20,000,

but the average is probably thirty per cent, less, and the expenses about

thirty per cent, of the total product. The average yield of the Fremont rock

is fourteen dollars to the ton, of the Sierra Butte rock eighteen dollars,

and that of the Allison company, according to report, has for more than a

year at a time been one hundred dollars per ton.

The cost of working quartz rock, including quarrying, crushing and amalgamating, is in the best mills from five to ten dollars per ton. The width of the vein, the softness of the rock, the amount of work done, and the skill and industry of the workmen, all are items of great importance in estimating the cost of quartz-mining. It is a business which the owner of the mill ought to understand. The cost of quarrying common quartz rock is about two dollars per ton, that is, for mill-owners that understand the business and superintend the labor themselves. When given out by the job, it usually cost more. When quartz is crushed in a custom mill, that is, a mill built to crush for all applicants, the cost is rarely less than five dollars per ton, and in Washoe, the price was at one time thirty dollars per ton ; but in the large mills, where many tons are crushed every day, is about two dollars per ton.

Continue on to:

Quartz Mining Advances

Return To:

Hard Rock Quartz Mining and Milling

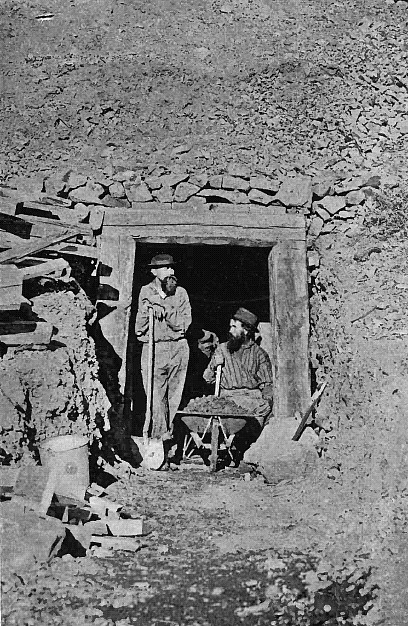

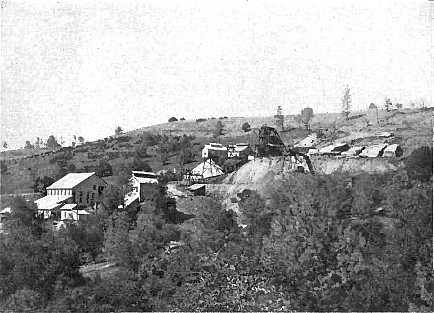

Above: A California Mother Lode Mine