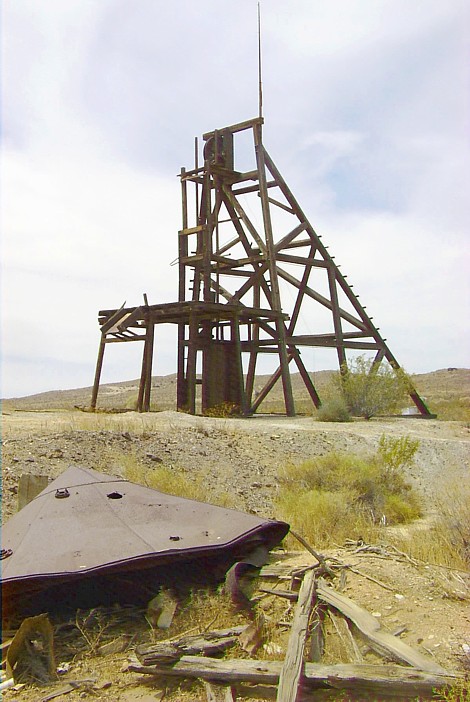

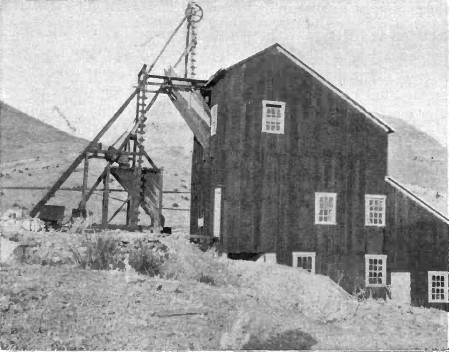

Construction Site of a

Shaft.

Place a shaft on level ground or in a valley near the center of the works.

Works however are usually located to suit the shaft and not vice versa. A

shaft should not be on swampy ground or where it may be flooded. Shafts near

the sea have been lost by tidal waves. It ought not to be too near a

building or too far distant from a road or canal. It must be remembered that

the engineers require a water supply. The mouth of a shaft should be 20 feet

above the surrounding level. This enables a bank or stage to be constructed

from which the material from the mine may be readily discharged. Shafts are

usually sunk from the surface but as in the case of long adits, which to

expedite the work maybe commenced at several points along their length, a

shaft may be sunk from the surface and from several levels, the manner on

which the different holings meet being dependent in the accuracy of the mine

survey (Ex. Konigin Marie Shaft, Hartz Mts).

In coal seams, sink on the dip side of the bed and on the dip side of an ordinary fault. With a reversed fault or where the seam dips against the fault, it may be better to sink on the rise side. A shaft may be vertical or inclined, in a lode, or outside in the country rock. Its long side is placed parallel to the strike of vein. Vertical shafts are usually sunk on the hanging wall or dip side of a lode, to intersect the lode at about half the maximum depth of the intended workings. This arrangement gives a minimum length for the cross cuts. Such a shaft does not explore the lode or help to pay the expense of sinking. It is good for a quick out-put and saves expense in winding, pumping and (for shafts of equal depth) in timbering.

If a lode is nearly vertical, the shaft may be sunk entirely on the foot wall side. There is less chance of dislocations taking place in the walls of the shaft. A rectangular shaft ought to be sunk with its long sides transverse to the cleavage or bedding of the rocks through which it passes; this may prevent the sides from slabbing off. It is assumed that the plane of bedding is nearly vertical. An inclined shaft in a lode is usually cheaper to sink, and it may be drier than a shaft in the country rock. While sinking, the lode is explored and ore is won. If it is in the country rock it ought to be on the foot wall side of the deposit. It is longer than a perpendicular, shaft, and there may be more movement in its walls. For these reasons more timber and other materials are required. Mechanical arrangements may be complicated and wear and tear is increased. There may be difficulties in opening parallel veins near such a shaft. Form and Size of Shafts. Rectangular, square, polygonal, elliptical or circular. Rectangular shafts are common at metal mines ; the two long sides being formed by the side of the lode, the two ends being portions of the lode and forming shaft pillars. On the Comstock lode the end pieces are 5 to 6 feet, while the wall plates forming the long sides, are from 20 to 24 feet. More ordinary dimensions are 4 feet to 10 feet by 9 feet to 16 feet. Rectangular shafts are convenient for dividing. Square shafts are stronger than rectangular shafts and require less material for a given sectional area. Circular shafts are usual at nearly all coal mines, they are the, strongest, most easily made water tight, give the largest area for a given periphery, but they are not so convenient to divide. A common diameter is 12 or 14 feet but for costening 4 feet may be sufficient.

Shaft Timbering. Shafts in lodes sometimes only require timbering on their shorter sides, the longer sides being the walls of the lode. This timbering consisting of sets and laths is very similar to that used for the roof of levels. Timbering a shaft 10 ft. by 7 ft. with sets and laths, the sets of 9 inch timber 4 feet apart, the laths 12 inch thick, costs about 3.10 per fathom of depth (Collins). Prop-crip Timbering;. On the surface a day frame with bearing ends is placed. After excavating 8 or 9 feet, bearing stemples are wedged across the shaft from the hanging to the foot wall. On these a crib is laid, and on the crib 4 props which carry a second crib and so on until the last props bear against the under side of the day frame. Wedges are driven in between the cribs and the sides of the shaft. The bearing stemples may bear and rest on blocks. The distance apart of cribs may be 2 feet 6 inches to 4 feet. Lagging may by used behind the cribs. If the wall plates of cribs are liable to be bent, they may be propped by cross bars, buntons or dividing, and to prevent cribs being forced out of shape, inclined struts or stringing planks are used. Stringing pieces may be notched against the cribs and held in position by cross bars, or spiked, When one frame or crib is placed upon another the lining forms solid crib timbering.

Frames are kept apart by cornerpieces, stiiddles orjogs. Plank or Box Timbering;. This consists of planks 6 inches or 8 inches deep and 2 inches to 4 inches thick, notched together to form a box ; the ends of the sides of which may be left projecting. These boxes are supported by their ends or on stemples, and they are packed behind with attle or clay. This timbering is only suitable for small shafts. Circular shafts may be lined by planks bent to form hoops with lagging behind or with wooden cribs built up in sections and propped apart. These are lined on the inside with planks, on the inside of these again lighter cribs may be placed. Where the pressure is great, the cribs may be 9 inches X 7 inches. In sinking, a depth may be reached equal to the length of the lagging, say 9 feet. Here a crib is placed and the lagging placed behind it. A second crib is then placed on props (punch props] at a height of 3 feet in front of the lagging, and so on up to the surface. The excavation now proceeds another 10 feet, parallel with the inside face of the crib first inserted, which may be supported by rods, chains or stringing deals from the surface, by driving in bars beneath it, by props from below, or by a portion of the earth or rock beneath it, this being removed gradually. Solid Crib Timbering. Where pressure due to a head of water has to be resisted, one solid crib is placed upon another. The lowest in the series is usually a wedging curb or crib. The cross section of the timber out of which it is built is greater than that of the cribs it carries. Between it and the walls of the shaft there is a plank sheathing which is forced back against a bed of moss by a series of wedges the moss being between the sheathing and the walls.

Driving in Soft Ground.

Spilling, is timbering which is carried on simultaneously or partially in

advance of the work of excavation, in running or quick ground. The spills

are planks about 2 inches thick, 4 inches wide and 6 or 7 feet long. These

are sharpened by slightly beveling one end so that when they are driven into

the soft ground horizontally they rise or diverge. The method consists in

driving spills into the end of a level and then excavating. The spills are

supported as the excavation proceeds. If the ground is very quick, breast or

closing boards will be required to support the face of a level. This method

has some resemblance in principle to that which, in 1823, enabled Brunnel to

drive the Thames tunnel, the sectional area of which was 38 feet by 22 feet

6 inches. He employed a shield of iron made up of 12 frames with 3 cells in

each. The shield was forced forwards by hydraulic rams, and brick work

inserted in the space thus gained. To relieve the pressure behind, the

shield the cells could be opened. Mr. Victor Simon, a Belgian engineer,

devised a plan for penetrating soft ground which has succeeded where

ordinary spilling has failed. This consists in covering the floor, roof and

face of a level with a mass of conical wedges each about 3 feet long. As

these are driven forwards, the space which is opened is filled with solid

door sets.

The thickness of an arch in feet = .0694 X radius in feet + I foot. It should not be less than 9 inches. The height of crown = 3 inches to 6 per yard of span. Under pressure, 8 inches per yard. For inverted arches 3 inches per yard. An arch 2 feet wide and 1 1 inches thick will hold 45 feet of attle. The pressure is the weight of the attle less its own friction.

In an inclined lode, arches to carry attle are placed so that their springing line is at right angles to the dip. Side walls have a batter of I inch to 12 inch per yard. For watertight walling, the joints are increased from 1/4 inch to ½ inch. Walls are destroyed by splitting, buckling, shearing and overturning. For a wall not to be overturned, the line of resistance, which for a rectangular wall is an hyperbola, must fall inside the foot of the wall.

Crushing strength in lbs.

per square inch:

Brick 500 to1,000 lbs.

Limestone 4,000 to 5,000

Granite 5,000 to 10,000

Dry walling only, resists crushing. In English bond, a course consists entirely of headers or of stretchers., while in Flemish bond, each course consists of headers and stretchers. Open spaces between masonry and the roof or sides of levels must be carefully packed. Sand forms a good packing.

Continue on to:

Arastrras and Chilean Mills

Return To:

Hard Rock Quartz Mining and Milling