In the development of a gold field from its first discovery by prospecting up to the complicated methods of extraction of quartz, cooperation is necessary. I mention this important point in the beginning of this discussion, because it is basic in the consideration of the industry and of society founded upon this industry, and because in common conception the individualism of placer mining and society is often greatly exaggerated. The "lone prospector" in the period we are considering was largely a myth.Prospecting was carried on, as a; general thing, in small organized parties, consisting of five or six up to perhaps fifty men. Careful preparations were made, particularly with respect to providing horses, food, arms, and mining utensils. The latter would consist of picks, shovels, and always "pans" vessels of iron or tin six or eight inches deep and a foot or more in diameter at the bottom, useful not only in "panning out" gold, but also for mixing bread. These companies were composed of experienced miners, generally "Californians." Immigrants from Missouri, Minnesota, the States, or England did comparatively little prospecting. It is interesting to notice, however, the presence of Georgians in Cariboo, Alder Gulch, and at Last Chance. For weeks and months an expedition might range over hundreds of miles of mountains, valleys and canons, studying the geology of the country, prospecting wherever indications were good, and once in a while fighting Indians.

Often failure resulted, but sometimes came one of the most thrilling and exhilarating experiences in the whole gamut of human endeavor, when sufficient amounts of the golden “color” was found, and the scales assured two dollars and forty cents per pan or twelve dollars and thirty cents from three pans, one miners could produce perhaps one hundred and fifty dollars for a single day's work! When diggings affording such prospects were discovered, the next step was to stake claims. One should not think of a placer claim as approaching in size an agricultural claim. Conceive a gulch (such as Grizzly, back of Helena) nine miles long, the flat portion one hundred or more feet wide between hilly or mountainous sides. Claims in such a gulch would generally extend from hill to hill and be in width one hundred feet. The claims were numbered up and down the gulch from the "Discovery" claim. Discoverers were entitled to one claim by preemption and one by discovery. Later comers were entitled only to a preemption claim. As a general thing a man could purchase in addition one claim, but sometimes, when a camp was quite thoroughly worked, more than one. If the flat was wide, claims would be from 100 feet square to 250 feet square, dependent on the district laws. The British Columbia code allowed only 100 feet square, while in the American territories there seems to have been a tendency to expand the size of the claims. A man could hold claims such as the above in more than one district, and besides he could hold claims on different kinds of placer ground. The claims on Alder Gulch were bar and creek; in British Columbia there were bar, creek or ravine, and hill claims.

It should be carefully noticed here that the plan of a mining camp corresponded more nearly to that of a town than to that of a country district. While the camps themselves were scattered and isolated, within each camp the structure was comparatively concentrated. Hence, again, we see that combination, co-operation, and organization are basic factors in mining life. Having staked their claims, the discoverers of new fields from lack of supplies or fear of the natives were generally compelled to return to some camp or trading centre. There the news invariably leaked out (a man surely must tell his friends, for whom he had already probably staked out claims), and a local rush ensued. Day laborers, who constituted four-fifths of the population of mining-camps, late-comers, who came in crowds into every large camp, and claim-owners who were not making topnotch figures would drop every employment, put up every dollar for outfit (or go without), and plunge for the new diggings. The great desideratum was to be the first on the ground. Merchants and packers, also, would press forward their trains eagerly, for the man who got a well- laden train into a new mining community would make a good-sized fortune. A vivid picture of the fever of a rush is furnished from Oro Fino when the news of the Salmon River diggings reached the town: "On Friday morning last, when the news of the new diggings had been promulgated, the store of Miner and Arnold was literally besieged. As the news radiated and it was not long in spreading picks and shovels were thrown down, claims deserted and turn your eye where you would, you would see droves of people coming in 'hot haste' to town, some packing one thing on their backs and some another, all intent on scaling the mountains through frost and snow, and taking up a claim in the new El Dorado. In the town there was a perfect jam a mass of human infatuation, jostling, shoving and elbowing each other, whilst the question, 'Did you hear the news about Salmon River?', 'Are you going to Salmon River?', 'Have you got a Cayuse?', 'How much grub are you going to take?', etc., were put to one another, whilst the most exaggerated statements were made relative to the claims already taken up Cayuse horses that the day before would have sold for about $25 sold readily now for $50 to $75, and some went as high as $100. Flour, bacon, beans, tea, coffee, sugar, frying pans, coffee pots and mining utensils, etc., were instantly in demand. The stores were thronged to excess. Pack trains were employed, and the amount of merchandise that has been packed off from this town to the Salmon River diggings since yesterday morning is really astonishing.

When an ardent crowd like this reached a gulch or basin, and when successive crowds from farther camps and towns began pouring in, the available mining ground was soon occupied. Before much work was done, however, a miners' meeting was held, and the district was organized by electing a miners' judge, a sheriff, and a recorder and by passing the rules of the camp. Men who had been schooled in California gold rush camps not only had learned to mine skillfully, but turned spontaneously to that form of local political organization which had been evolved in California. This was true not only in the American territories, but also in the British; along Fraser River and in Kootenai steps were taken in organization prior to the arrival of the British officials, and the success of these officials in maintaining law was due in very considerable degree to the orderly instincts and methods of the California miners. One of the most important of the district rules was that concerned with representation. Representation meant the time required for work in holding a: claim. Ordinarily one day out of seven was required during the working season, although, sometimes, as in Bivens Gulch (Montana) two days at first were necessary. A man might do the work himself, or have it done. In British Columbia it was required that representation be bona-fide and not colorable, and a claim was considered abandoned if left seventy-two hours. Bona-fide representation, however, included clearing brush for cabin, building cabin, cutting timber away from the claim for works on the claim, and bringing in provisions.

The time when representation was not required or, in other words, when claims were "laid over 7 ' was determined in the American territories by district meeting, in British Columbia by the local gold commissioner. Claims were universally laid over during the winter season, but might be laid over temporarily at other times as for example, during prolonged drought. The British Columbia method of control seems to have given greater flexibility for adjustment to conditions. "When claims were laid over, miners could absent themselves entirely until representation was again required, and no one could legally jump their claims. This arrangement gave miners an opportunity, perhaps, to return to their homes for the winter, if they chanced to live in the Willamette or some Coast community, or at any rate, to go to some town, as Victoria, Portland, Lewiston or Boise, where living was cheaper than in the mines, life more attractive, and the chances for spending all one's money very good. Here, then, is another peculiarity of a mining camp : men seldom thought of creating homes in such a camp, and ownership was based not on residence, as in agricultural homesteads, but on work during a portion of the year.

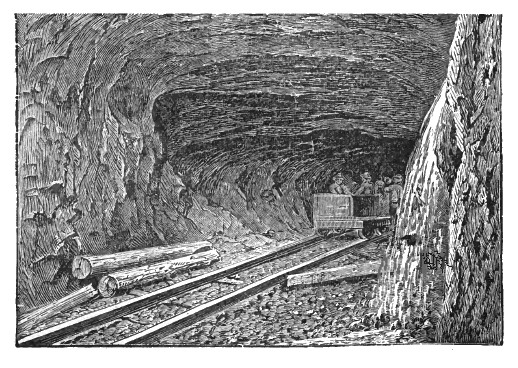

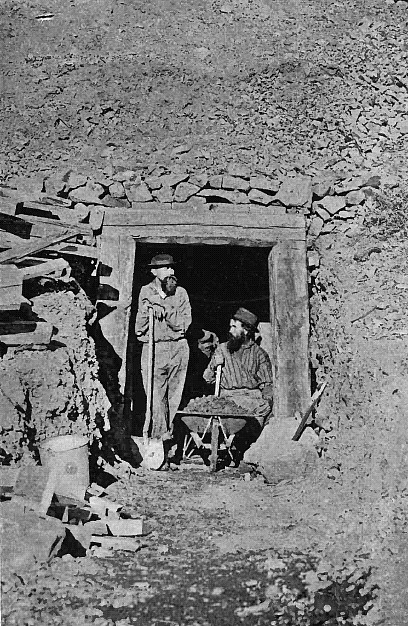

Still, it would be wrong to think that the camps were wholly deserted during the winter. A very considerable proportion of the miners stayed, and these occupied themselves in sawing lumber, making sluices, etc., and (especially in deep diggings) in digging shafts and drifting. Mining operations in the latter class of diggings could be carried on all winter. Camps often acquired, therefore, more of stability than is commonly thought. It is time, however, to return to the recently discovered and newly organized district where the miners were ready for their work. Theirs was a busy and laborious life, and it did not consist of picking up golden nuggets out of streams and spending most of their time in hilariousness and adventure. Work, hard physical toil, was necessary to development. In the first place, there were cabins to build, and in this labor British observers admired the skill of the American axmen a skillfulness particularly noticeable in Missourians, or those recently from the "States." Ditches were to be dug and sluices and flumes constructed. Lumber had to be obtained by the laborious process of whip-sawing, and good whip-sawyers could always make high wages until the inevitable small sawmill arrived. The processes of placer mining were somewhat varied. The simplest, after the pan, was the use of the rocker, which was an affair constructed somewhat like a child's old fashioned cradle, having at one end a perforated sheet of iron. The rocker was placed by the side of a stream and one man rocked and poured water, while another dug and carried dirt. This of course was a slow process, and a next step was the use of the sluice. Boxes ten or twelve feet long, twelve inches wide and eleven inches deep, were arranged in ''strings" in such manner as to allow a current of water from a ditch to be run through the boxes. In working such a sluice a number of men could be utilized some to strip sod, some to dig and wheel, one to throw out pebbles and boulders with a sluice-fork and one to throw away tailings. Transverse cleats were nailed to the bottom of both rocker and sluice-box, and mercury was poured into the mixture of dirt and water in order by amalgamation to secure a larger percentage of gold than would otherwise be possible. A farther modification of the sluice was the use of hydraulic power, in the shape of a powerful stream of water from a hose, instead of picks and shovels.

Continue on to:

Evolution Of Mining Methods In The North, Part II

Return To:

Hard Rock Quartz Mining and Milling