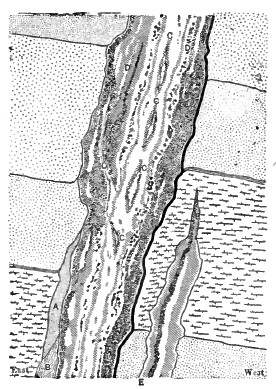

The pay dirt lay next to the bed-rock and in shallow diggings could be got at simply by stripping ; but in a number of rich fields (Cariboo and Last Chance, for examples) the pay stratum or lead was buried under twenty to sixty feet of stream detritus, and then shafts and drifting had to be resorted to. Drifting of course meant digging out around from the bottom of the shaft. This was work only for an expert miner, and a good drifter was always in demand at wages three or four dollars a day higher than those paid for ordinary labor. The use of shafts and drifts required timber for supports and the rigging of windlasses. Water and boulders often bothered greatly, especially the former. Sometimes pumps were made, but often a bed rock flume was resorted to. In its construction a miner opened up a ditch on the bed rock from a point low enough to drain his claim.In carrying on these various forms of mining labor, the skill of old Californians was pre-eminent, and everywhere from Cariboo to Owyhee the methods and opinions of Californians were given great respect. In camps where there were many "pilgrims" from the states higher wages were generally paid to old miners. The Californians, indeed, were apt to be a bit supercilious with regard to noviates; at Oro Fino, for example, they complained that the Willamette farmers in the mines did not know how to secure gold properly from the dirt to which the others might have replied that neither were they so expert in gambling it away after it was secured. The scorn of the expert for the unskilled is somewhat amusingly revealed in a letter from Last Chance, where, the writer says, the gulches were mostly taken up by Pilgrims, who know more about raising wheat or cranberries, or handling logs, than using pick and shovel. Just watch them handle a pick.

A good miner has a pick drawn to a fine, sharp point; he works underneath the pay dirt on the bed rock ; you know, Mr. Editor, when you knock away a man's underpinning he is easily brought down; and so it is with gravel get under it with a good long, sharp pick, and it is easily brought down. It cannot stand on nothing; but a green horn has a short, thick, stubbed pick; he stands on the top, like a chicken on a grain pile; gets out one rock and finds he has another below it requiring the same labor. Yet there was good demand in every thriving camp for many kinds of labor, so that men turned easily to that employment in which they had had previous training. Notwithstanding the comparative skillfulness of the Californians, however, the placer mining of this period was wasteful, and unconscious of conservation. This for two reasons: In the first place men were in the mines simply to make as much money as they could and get away in the shortest possible time. This was particularly true, of course, with regard to residents of the Willamette or of Missouri, to many of whom a trip to the mines was of the nature of an excursion, designed to make a little money or pay off a mortgage. In the case of the habitual miner there was no possible way by which he could be constrained to work old ground carefully, when he could make large sums by hastily working and then flying off to some other field. A man certainly could not be expected to work carefully a claim that did not pay more than wages. In the second place, the expenses necessarily attendant upon opening a new and remote placer field by the modes of transportation which then obtained, were so great a charge upon the mines that only the very richest gravel could be profitably worked. These placer mines had to pay for establishing routes of transportation and for nurturing civilization under unfavorable conditions. Whatever the reason, at any rate, the mines were skimmed, and the wastage was enormous.

Mr. J. Ross Browne, who had spent years in the mining regions and who had opportunity to know the situation better than anyone else in the United States, in his report of 1868 though he does not mention his authorities] says that, "At a moderate calculation, there has been an unnecessary loss of precious metals since the discovery of our mines of more than $300,000,000, scarcely a fraction of which can ever be recovered. This is a serious consideration. The question arises whether it is not the duty of government to prevent, as far as may be consistent with individual rights, this waste of a common heritage, in which not only ourselves but our posterity are interested. It was true that waste was to a considerable degree relieved by the incoming of the patient Chinese into every camp after the cream had been taken by the whites, by the introduction in some cases of hydraulic processes by which low grade ground could be profitably worked, and by more careful methods of whites who were content to labor on after the flush times were over. But it remained a fact, and a fact of importance in sociological study of early mining society, that mining communities economically based on placer mines were wasteful and unstable. In order to overcome this instability, everywhere the more substantial miners, business men, and statesmen turned their attention to quartz. In all mining regions, therefore, whether in British Columbia, Idaho, Oregon, or Montana, quartz lodes were eagerly located and attempts, more or less elaborate and successful, were made at development.

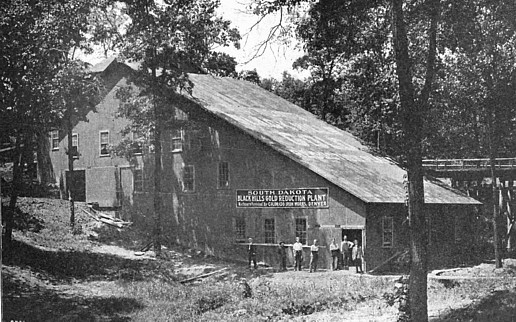

The simplest machinery for working quartz was the arrastra (or arrastre), originally a Mexican invention. This consisted of a circular area paved with stones, in the middle a post and to this post attached a sweep to which a mule or horse was hitched. A block of granite, fastened to the sweep, was dragged around over the quartz distributed within the circle. The remains of these old arrastras may be found in many gulches today. Their use "required neither capital nor a number of laborers. The owner of the arrastra could dig out his own rock one day, and reduce it the next. The enterprise of Americans, however, forbade contentment with such rude machinery, and they at once set to work, in spite of enormous obstacles, to construct mills. The first mill in Montana is thus described by one of the pioneers in quartz: "An overshot wheel, twenty feet in diameter, is placed on a shaft 18 feet long, with large pins in the shaft for the purpose of raising the stamps. These stamps are fourteen feet long and 8 inches square, and strapped with iron on the bottom, which work into a box that is lined on the sides with copper plate galvanized with mercury, so as to catch the gold as the quartz is crushed and clashed up the sides of the box. Then we have an opening on one side of the box, with a fine screen in it, through which the fine quartz and fine gold pass, and run over a table covered with copper.

More elaborate mills, of course, were constructed, as outside capital was enlisted, and these mills represented what may be called a second stage in quartz development. The study of the reduction of gold and silver in such a mill was fascinating. The quartz was first broken into fragments the size of apples by sledge hammers and then shoveled into feeders, which brought it under large iron stamps, weighing three hundred to eight hundred pounds, and which "rising and falling sixty times per minute with thunder and clatter," made the building tremble, as they crushed the rock to wet powder. Quiet, silent workmen run the pulp through the settling tanks, amalgamating pans, agitators and separators, refuse material passing away, and mercury collecting the precious metal into a mass of shining amalgam, soft as putty. This goes into the fire retort where it leaves the quicksilver behind and finally into molds whence it comes forth in bars of precious metals. The building of such mills and the working of quartz claims required the use of capital and corporate methods. The vast and significant development in the mining industry during the decade 1860-70 was the supersession of surface placer mining methods wherein the individual working in informal combination had free play, by quartz mining and corporate working of deep placer diggings, wherein individualism began to be submerged and capital became uppermost.

The necessity of this process is clearly apparent when we look at the position of an ordinary miner who had discovered and perhaps tested a good quartz lode. He could with some trouble get his claim duly recorded and, with more trouble, do or have done the assessment work required. But what then? He did not have money with which to work his claim, and he could not pay his expenses of living as he could from a placer claim. Hence, if he was to realize on his claim, he must inevitably sooner or later call in capital. It is true that some few placer miners saved enough to equip small mills and that there was some evidence of cooperative organization among the men, but in general there was a great call from the mining fields for the application of capital. Accordingly, we find effort on the part of local claim owners to interest outside capital. Portland capitalists invested at Powder River and Owyhee. There was some connection, also, with San Francisco. But New York was the place towards which effort turned most yearningly. Hardly had the Owyhee quartz been discovered, when Gen. McCarver started east to interest the New York capitalists.

Continue on to:

Evolution Of Mining Methods In The North, Part III

Return To:

Hard Rock Quartz Mining and Milling