Three principal conditions control the choice of a hydraulic property, namely: First, the amount of gold in the deposit, which must be sufficient to cover cost of purchase, equipment and maintenance and further pay interest on capital invested; second, an ample water supply, accessible and under sufficient head to ensure effective washing of gravel to and through the sluices; and third, sufficient fall to permit proper treatment of gravels and disposition of tailing. Besides these, other important considerations are: the presence of timber, and in such quantities as to furnish lumber for sluices, flumes, trestles, sluice blocks, etc., not too high-priced labor, and transportation facilities. When wooden sluice boxes are put in the cuts, they must be anchored down. The riffles or blocks are then placed, the sluice obstructed temporarily, and run full of sand or gravel to wedge in the blocks, then the obstacle is removed and the material is run out of the sluice with a giant or a strong stream of water. Sluices should not be less than 240 feet in length, owing to loss of fine gold, especially when clay is present. Blocks should never be wedged into a wooden sluice or flume as they will spread the box on swelling. They may be prevented from floating, by nailing a scantling on top of the blocks, and against the side of the sluice.1 Along the side of the sluice-boxes and at various intervals, large shallow sluices are placed, which are called "under-currents." They vary from 20 to 50 feet in width, 40 to 50 feet in length, and have sides some 16 inches high. These under-currents are set at a fairly heavy grade, being placed to one side of and a little below the main sluice, the object of which is to relieve the latter of the finer material, and thus permit a more effective collection of the gold.

The coarse stuff passing the grating through which the fine passes to the under-current, may be picked up by a sluice at a lower level, or be permanently disposed of by being thrown on the dump. The fine material entering the under-current, which is set at a grade of 8 to 10; per cent, passes over cobblestones and block riffles, and may then be returned to the sluice at a lower level. Long sluices, usually four to six feet wide, and four and one-half feet deep are economical gold savers while short ones with moderately high grades and clayey materials may cause a loss of 10 to 40 per cent of the gold. The following are common causes of loss of mercury, which may amount to 12 to 15 per cent: velocity of current, length of sluice and time of run, temperature of water, character of material washed and method of charging mercury. Pipe clay and leaky flumes are claimed to be the greatest sources of loss of both gold and mercury. When properly operated well devised sluices should save from 90 to 98 per cent of the natural gold, and from 98 to 100 per cent of the coarse gold. The occurrence of gold in sluices is given as follows: First recovery, 1st 15 boxes 73.5 per cent; Second recovery, next 30 boxes 13.4 per cent; Under -currents 11.5 per cent; Recovery below under-currents 1.6 per cent; A general clean up takes place only once or twice a year, when the sluices are thoroughly over-hauled and repaired preparatory to making another long run.

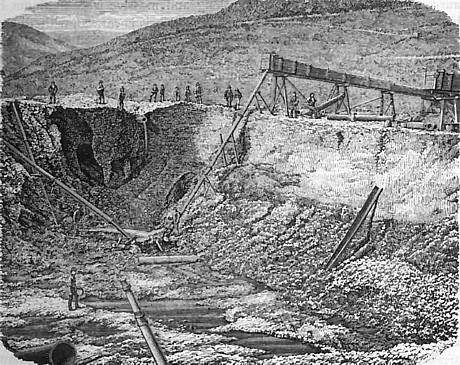

Developed in the early days of the California gold rush, by the late eighteen seventies hydraulic mining had become one of the most important industries of California, in which more than $100,000,000 had been invested, in mines, reservoirs, canals, and equipment. The debris deposited into streams by the hydraulic mines was huge and significant damage was done to farming lands in the valleys adjacent to the Sacramento river and its tributaries, as they became buried in tailings many feet deep. This became so objectionable to agricultural interests that the method was stopped by court injunction in 1884, and afterward hydraulic placer production dropped to a very low level. After the injunctions, hydraulic mining was almost entirely discontinued, until the passage of the so-called Caminetti Act, early in the 'eighties, which permitted the resumption of hydraulic mining under the permit and restrictions of a corps of United States engineers, known as the Debris Commission. The Debris Commission's work is directed entirely to controlling the natural detrital flow, and although appointed for this work about 1883 and at present employing conscientious and efficient engineers, their whole work to date has been confined to, the Yuba river, where practical results were only accomplished beginning in 1904.

At the time, it was commonly supposed that the efforts of the Debris Commission was to restore the practice of hydraulic mining throughout the State, but such was not the case, nor does there appear to be the slightest hope for a largely increased output from this source in the future. It is true that under certain conditions the chief of which is that the miners provide impounding dams or settling basins for the tailings they produce, some approved mines were allowed to continue their work. However, the formality which was required and the expense of this work as a rule prohibited large hydraulic workings and the output from such mines because their tailings were considerable. This meant the mines which operated afterward were tiny compared with the product of former hydraulic mining operations.

The deposits of frozen gravel in Alaska present special difficulties to hydraulic mining operations. A further obstacle to be contended with is an inadequate water supply. Quite extensive hydraulic mining operations are, however, being carried on in the Nome Region, where the overburden of barren ground is as a rule thinner than in the Klondike. On Anvil Creek the overburden is only two or three feet thick, below which are from three to six feet of pay gravel, the whole of which can readily be run through the sluices. Placer operations ranging from a gold pan to hydraulic mining are employed; rocking, small scale sluicing and the use of dredgers and steam shovels are common.

No great difficulty is experienced in breaking down the frozen ground but to disintegrate it preparatory to entering the sluices, it must be kept under water sufficiently long to thaw out. In working frozen gravel the sun is at times depended upon to thaw several inches of the surface which is then washed off by the giants. It is therefore evident that in a mine of any considerable capacity, such that several giants can be kept busy, a large area must be operated upon, which is systematically worked from one end to the other and back again. However, when the gravels are dry frost troubles but little and thawing by solar heat is unnecessary.

Continue on to:

Bucket line dredging of placer gold deposits

Return To:

Historic Placer Mining Technologies