It is a curious and little appreciated fact that the miner is the scout of civilization. He braves the savage, the desert's heat, the Arctic's cold. Alone, he fearlessly penetrates regions wherein his foot is the first to tread. It was the pursuit of golden dreams that sustained the weary marches of the Spanish explorers of America. Thus it was with Arizona. Coronado's quest, four hundred years ago, was for the gold of the Seven Cities. Though the Spaniards found no native gold in Cibola, they found it elsewhere, and for centuries the greatest revenues of the Spanish crown were from mines now included in Southern Arizona. The Spaniard mainly confined his operations to Pimeria. Among peaceable tribes. The Anglo-Saxon went even farther when he came into possession of the land. There is not a valley in Northern or Eastern Arizona that has not its tale of prospectors ambushed by Apaches. Yet, step by step, the Apaches were driven back. Following the prospector and the miner came the trader, the cattle rancher, the farmer, the home seeker, till today Arizona's civilization, based upon the mine, is as sound and as modern as is that of much older commonwealths. No longer is mining the only industry, but it is still the chief. It is well that it is so, for the dollar from under the ground is a new dollar and a whole dollar. The bright golden bar from the assayer’s den in the stamp mill means so many more actual dollars added to the money in circulation; every drop of the fiery stream from the converter's lip, means just so much more permanent wealth brought into being for the good and use of mankind. And mining has passed the experimental stage. "Luck" counts for little in the business.

Nearly every great fortune of the West has been made in mining, and nearly every fortune has been made by men of good, hard horse sense, who went in on their judgment and not on their hopes and enthusiasm. Though many of the people of Arizona for years clung in affection to the 16-to-l theory, it was a fact that the demonetization of silver really had little effect upon Arizona. Broadly' stated, almost every silver mine within the territory had closed before silver had sunk below a dollar an ounce. The famous old Arizona silver mines at McCracken, Tombstone, Silver King, Richmond Basin, Mack Morris and in the Bradshaws have about all had been closed down and their production no longer enriches the residents of the state. At present there remains very little exploration for silver ore outside of a limited portion of Mohave County.

OPTIMISTS OF THE HILLS

The professional prospector of the Southwest is practically of the past. As

a rule he lived on a "grub stake" furnished by a group of individuals in the

town wherein the prospector made his headquarters who are willing to make a

gamble. The law of such co-partnerships was definitely recognized. As a rule

there was no very close agreement made between the parties; rarely was any

contract put down in writing, but the unwritten law of the land was that the

man who furnished the "grub stake" got a half interest in any location that

was made by the prospector during the time when he fed upon "grub" furnished

by his urban partner. It was rare indeed that such agreements were violated.

The prospector nearly always kept faith. The system came into Arizona from

Nevada and California, where many of the fortunes realized by country

storekeepers, saloonkeepers and gamblers came through modest "grub stakes"

furnished to some old prospector who made a big strike. The prospector's

outfit was of the simplest, in keeping with his life and taste. There was

always a burro, usually one that had had years of experience in the

prospecting game, and that never strayed far from the camp, however

transient it might be. Wonderful tales are told of these prospecting burros

of old; they were fond of bacon rinds, and would always leave the sage brush

and catclaw, upon which they were supposed to thrive, to join the prospector

in consuming the last of the baking-powder biscuits.

The prospector of old was a man sustained by a boundless faith and never quenched hope. In reality he was a gambler of the most pronounced type; every hill held for him the chance of a bonanza, and no rocky point was passed without an investigating tap from his hammer; every iron-stained dyke had to be sampled in his gold pan. Most of the prospectors were overly sanguine; they fairly loaded themselves and their principals down with prospects, on which the annual assessment work would have cost far more than the value of the ground. Many a prospector has boasted that he held even 100 locations. To have fulfilled the letter of the mining law, such a number of claims would have necessitated the expenditure of $10,000 in annual assessment work, yet the individual speaking might have assets on which could not have been realized $10. All through the hills of Arizona are to be found the monuments left by these prospectors, where they first located and then tested claims that were worthless in nearly every instance. They were looking for sudden riches, and failed to understand the philosophy of the latter-day miner, worked out by hard experience, that mining, after all, is a manufacturing industry, and that the greatest profits are not found in rich pockets of silver and gold ore, but in the percentage of income over expense that can be gained by the working of large quantities of ore of fairly uniform grade, handled almost mechanically and under the most economical conditions.

The prospector's life was rough, and yet not particularly laborious; he drifted through the hills on trips that were limited only by the quantity of grub he carried or could command. As a rule he slept out in the open, whatever the weather, and his diet was based unendingly upon bacon and black coffee, with sour-dough or baking-powder bread on the side. Tobacco, of course, was an absolutely essential feature of his ration. "When the trip was up and his locations had been recorded, rarely did the professional prospector ever work upon the mines he had found. If the i5nd proved good, he sold out for some modest sum, which he often spent in dissipation. Then it was back again to the hills with the same old burro, living a life which he would not have exchanged for any other.

A very different type was the miner who did occasional prospecting, usually when he was out of work or when he got tired of the darkness underground and wanted a trip into the hills in communion with the face of Nature, instead of her heart. A man of this sort usually paid his own way and held fast to anything good that he found. Not necessarily of higher type than the professional hunter of mines, he was of more substantial character and in hundreds of instances graduated into the class of mine-owning capitalists and became one of the leading citizens of his locality.

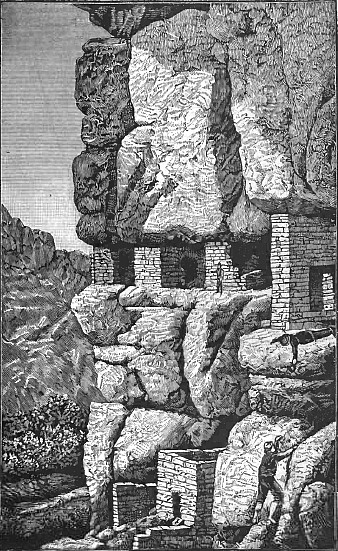

A BLIND MINER AND HIS WORK

Mohave County has given the world many

instances of rare courage in its pioneer days, but nothing finer than the

tale how a blind miner, Henry Ewing, unaided sunk a shaft on his Nixie mine,

near Vivian, not far from the present camp of Oatman. It was in 1904, after

Ewing, a gentleman of culture, had lost his eyesight. Despite the warning of

friends, he persisted in returning to his mine, where he rigged up leading

wires, to assure him a degree of safety and then set up a windlass over his

twenty-foot hole. He blasted and dug and hauled the ore buckets to the

surface and cared for himself in camp, his worst adventure an encounter with

a rattlesnake and narrow escape from death on the trail. Another experience

was falling from a ladder a distance of thirty feet, receiving serious

injuries, yet managing to climb out and to seek assistance at a nearby

mining camp. Almost as much pluck has been shown by several miners who have

developed their claims alone. In the Hualpai Mountains, Frank Hamilton

started upon such a work in 1874 and alone sunk two shafts, 100 and 50 feet

deep. In the same district a memorandum has been found of J. L. Doyle, who

alone sunk two 65-foot shafts and connected them with a drift. Enoch Kile, a

Yavapai County miner, single-handed sunk a 75-foot shaft and doubtless many

other such instances could be found.

Return

to The Arizona Page:

Arizona Gold Rush Mining History