Gold Mining At The

Famous

Nome Gold District

.

Gold Mining At The Nome Gold District

|

|

||

|

. |

Ever hear of the great gold rush to Cape Nome on the Bearing Sea? During the long summer, gold is still mined at this rich location as so many have seen on television. Interested in how that famous gold mining district was originally discovered? How about what opportunities there are in Nome for gold prospecting? If you have a pan, dredge or something else you may be able to get some of that placer gold - and that is what counts. Here is some information about Nome Alaska...... |

|

|

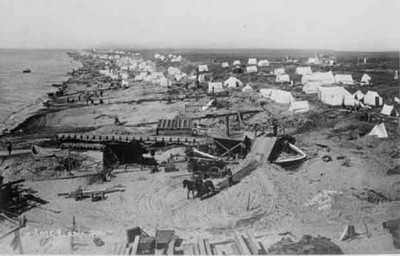

In September of 1898, H.L. Blake learned through an Eskimo of gold at Cape Nome and together with Reverend J.L. Hultberg, a Swedish evangelical missionary from Golovin Bay, Christopher Kimber and Frank Porter, they all went up to snake River and on Anvil Creek discovered gold that ran four dollars to the pan full. They did not state any claims, intending to keep their discovery a secret, so that they could return in the spring with provisions and outfits. But word leaked out, and other prospectors, braving the storms of that season, set out for Cape Nome and found on Anvil Creek even richer diggings than Blake’s, staked claims, returned to Counsel City, and claimed the honor of discovery. Once the secret was out, a great stampede from all the region around came to the Anvil Creek area. 400 men had reached Nome by January where they lived in tents until the spring. Many of the tributaries of the Snake River were staked and a community known as “Anvil City” was laid out at the mouth of the Snake River. The Nome district is the part of the Seward Peninsula drained by the Solomon River and other streams flowing into Norton Sound and the Bering Sea as far west as Cape Douglas. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

| In the Nome area, deposits representative of all major types of placers have been mined. The deposit on Sophie Gulch is a good example of a residual placer, although it has generally been referred to as a lode deposit and was staked as two lode claims and one placer claim. Small scattered iron-stained quartz-feldspar and quartz-calcite veins and schist wallrock contain scheelite and sulfide minerals. Several tons of scheelite concentrates were mined from the weathered material above the lode during World War I and World War 11, but the lode itself could not be worked at a profit. Similar deposits on Twin Mountain and Glacier Creeks yielded a total of about half a ton of scheelite. Gold was recovered from residual placers on Pioneer Gulch and Boer Creek. Placers formed mainly by mass-wasting processes have not been described specifically, although such deposits must have been mined in the transition zones between residual and stream placers. | ||

|

|

|

Every means of mining from shovel to dredge has been used. Ditches and pipelines, some tapping sources as far away as the south flank of the Kigluaik Mountains, brought the water needed for large-scale operations. The Miocene ditch, the first major ditch constructed on the Seward Peninsula, was begun in 1901 and completed in 1903, paving the way for the integrated operations that made possible large-scale mining in the Nome area. The "high-bench" placers near Nome were preserved from subsequent erosion in the divide between the headwater gulches of Anvil, Dexter, and Dry Creeks in the saddle between King Mountain and the hills to the south. As these deposits were far from any dependable source of water for sluicing, only the richest material (at least $6 per yard) could be mined. Erosion of the "high-bench" placers probably contributed much of the gold in the rich stream placers in Anvil, Dry, and Dexter Creeks. A diffuse paystreak that Gibson (1911, p. 464-465) considered to be an old channel of Anvil Creek extends from the vicinity of Moonlight Springs, where the stream leaves the mountains, to the coast near the mouth of the Snake River. This deposit, considered by later geologists to be a marine abrasion platform deposit, was drift-mined locally and was later extensively dredged. Enough gold was recovered between 1904 and 1906 from a drift mine on one claim to make the operator a millionaire. Beach deposits have been a major source of gold in the Nome area since the present beach was found to be auriferous in 1899. As creeks that crossed the tundra between the shore and the base of the hills north of Nome were prospected and mined, other beaches were found. Although not the bonanzas of the richest parts of some of the creeks draining Anvil Mountain, many parts of the beaches were very rich by any other standard. Collier and others (1908, p. 159-165), Gibson ( l g l l ) , Moffit (1913, p. 109-123), and Hopkins, MacNeil, and Leopold (1960), among others, studied these deposits, recognized their origin, chronicled their exploration, and speculated on their chronology and the events in the complex regional glacial history that allowed their formation and preservation. Interest in finding possible submarine beaches off the coast led to extensive offshore studies by both Federal agencies and private companies. |

||

The following discussion of the beaches and offshore deposits is based mainly on a report by Nelson and Hopkins (1969). Eustatic fluctuations of sea level during Pliocene and Pleistocene time resulted in shifting the strandline as far inland as the base of the hills (Fourth beach) and as far offshore as "76-foot beach". A beach deeply buried a short distance offshore and the so-called "Inner" and "Outer Submarine Beaches" are of Pliocene age ; the others are probably Pleistocene. Fourth beach is generally too lean to be mined at a profit, although it has contributed gold to minable placers that were formed in streams that cut through it. Plans for prospecting and eventually mining any gold that may be found in the basal parts of the offshore beaches (which could not be sampled with the equipment available to Nelson and Hopkins) have not advanced beyond the formative stages. Onshore beaches, including the two Submarine Beaches, were mined in the early 1900's by drifting from shafts sunk from the surface. Dumps were accumulated near the shafts and sluiced with what water was available during the short spring runoff season. This water shortage and the inherent high expense of drift mining soon caused the amalgamation of large blocks of claims. Subsequent large-scale dredging, preceded by cold-water thawing of permafrost in areas to be dredged, allowed many of the remaining old beach deposits and much of the intervening auriferous glacial drift to be mined at a profit. Unfavorable economic factors rather than exhaustion of resources finally caused large-scale operations to cease at the end of the 1962 season. Production from the old beaches accounted for most of the gold recovered in the Nome area and possibly for as much as half of that reported for the entire Seward Peninsula region. |

|

|

Thin auriferous deposits not associated with old beach lines were recently found on the floor of the Bering Sea near Nome. According to Nelson and Hopkins (1969), these are in places where wave action during shoreline transgressions and regressions has winnowed fine material from glacial drift, leaving relict gravel resting on relatively unsorted till, outwash, and alluvium. Some samples of this material contained as much as $4 in gold per cubic yard, and about one-third of those recovered during the investigations of Nelson and Hopkins contained gold worth more than $1 per cubic yard (gold at $35.00 per fine ounce). The thinness of the relict gravel, which averages about 1 foot thick, could present serious technological problems for economic recovery of its gold. Gold in generally similar gravel on the sea bottom near Sledge Island about 25 miles west of Nome was probably derived from nearby bedrock sources that are now submerged, rather than from lode deposits on what is now the mainland. Sesimic profiling offshore from Nome located what are probably old buried stream channels that could be inviting exploration targets for larger mining companies. The commonest heavy minerals that accompany gold in placer concentrates in the Nome area are scheelite, magnetite, ilmenite, hematite, and garnet. Scheelite is so plentiful in some deposits that it has been produced from Snow Gulch, Rock Creek, and probably from a few other streams. Cassiterite has been reported from the Left Fork of Dexter Creek and from Glacier, Goldbottom, Monument, and Rocky Mountain Creeks but not in sufficient quantities to be worth saving. Stibnite and bismuthinite have been found at Boulder Creek and stibnite has been found at Dorothy Creek. Submarine beach contains the largest amounts of pyrite, chalcopyrite, and, in particular, arsenopyrite of any of the beach gravels near Nome or creek placers in the Snake River and Nome River drainage basins. The presence of these relatively "fragile" heavy minerals suggests an undiscovered nearby bedrock source that might also have contributed gold. East of the Nome River, at the point where Hazel Creek flows from the hills into the broad Flambeau River valley, there was placer mining in at least one year. A few miles beyond the divide west of the Snake River in areas geologically similar to areas closer to Nome, mining has been carried on in the basins of the Sinuk and Cripple Rivers. On the basis of incomplete data, most of the mining was apparently on Oregon and Arctic Creeks. Coal Creek, though very little gold was produced there, is interesting in that at least some of the gold has been re-concentrated from Tertiary coal-bearing rocks. Native bismuth and rutile have been identified in concentrates from Charley Creek and several other streams. Scheelite has been reported from Oregon and Nugget Creeks, and cassiterite has been reported from Fred Gulch. Near Aurora Creek widely distributed float carries a considerable amount of sphalerite and a little galena and chalcopyrite. The Solomon area is geologically similar to the Casadepaga area of the Council district and to the rest of the Nome district. A lode deposit near Solomon-the Big Hurrah mine near the head of Big Hurrah Creek was rich enough to be mined and yielded at least 10,000 fine ounces of gold between 1900 and World War 11 (Berg and Cobb, 1967, p. 126-127). This and a neighboring prospect contain enough scheelite to have been investigated as sources of tungsten. Several other lodes in the area were prospected for gold or antimony, but none was ever brought into production. |

||

Placer mining in the Solomon River valley dates from 1899, when the first claim was staked on the Solomon River near the mouth of Big Hurrah Creek. Stream and bench placers were worked until 1967, when activity had dwindled to two 2-man operations on Shovel Creek. Most of the gold mined was recovered by dredges from the Solomon River, its major tributaries, Shovel and Big Hurrah Creeks, and Spruce Creek, to which a dredge was moved from Shovel Creek in 1929. The richest gravels were probably those of Big Hurrah Creek below the Big Hurrah mine. The last dredge to operate in the area was dismantled about 1963 and the machinery was moved from the Solomon River to the western end of the Seward Peninsula. Stream and bench deposits in the Solomon area were mined by methods other than dredging, particularly on Kasson Creek, on Mystery Creek and its tributaries Problem and Puzzle Gulches, on West Creek, in the Shovel Creek drainage basin, and on Penny Creek. Scheelite is common in concentrates from Big Hurrah Creek and the Solomon River. Coats (1944a, p. 4) noted that analysis of a sample of a dredge concentrate from the Solomon River below the mouth of Shovel Creek indicated 22 ounces of gold and 9.1 pounds of scheelite per cubic yard of concentrate. There is no record that tungsten concentrates from the Solomon area were ever marketed. Other heavy minerals reported with the concentrates include magnetite, ilmenite, garnet, pyrite, chalcopyrite, and arsenopyrite. There has been some mining on at least three west-flowing tributaries of the Eldorado River, the largest stream between the Nome and Solomon Rivers. In the 1940's parts of Beaver and Pajara Creeks were dredged. Between 1900 and 1903, gold worth a few thousand dollars was recovered from Venetia Creek with less elaborate equipment. |

|

|

| A number of individuals still mine and prospect the Nome area. During the summertime, visitors work the famous Nome beach sands and recover a few ounces of fine flake gold. The best beach sand has high concentrations of garnet and iron minerals, but the garnet gives it a distinct deep red color. These concentrated zones are easy to recognize on the surface of the beach. There are also commercial suction dredging operations that work the beach deposits that are located offshore as the well known TV show demonstrates. The state of Alaska has set aside some offshore area for those who want to dredge for gold. Be careful however as the seas here are cold and unpredictable. Stormy weather happens regularly even in the summertime. In addition, the GPAA organization has its popular Alaska facility not far north from Nome. | ||

Want to know a little bit more about this crazy prospector guy? Well, here's a little bit more about me, and how I got into prospecting: Chris' Prospecting Story